|

Notes

and References It may

be as well to give the reader some account of the enormous extent of

the Celtic

folk-tales in existence. I reckon these to extend to 2000, though only

about 250

are in print. The former number exceeds that known in France, Italy,

Germany, and

Russia, where collection has been most active, and is only exceeded by

the MS. collection

of Finnish folk-tales at Helsingfors, said to exceed 12,000. As will be

seen, this

superiority of the Celts is due to the phenomenal and patriotic

activity of one

man, the late J. F. Campbell, of Islay, whose Popular Tales and

MS. collections

(partly described by Mr. Alfred Nutt in Folk-Lore, i. 369-83)

contain references

to no less than 1281 tales (many of them, of course, variants and

scraps). Celtic

folk-tales, while more numerous, are also the oldest of the tales of

modern European

races; some of them — e.g., "Connla," in the present selection,

occurring in the oldest Irish vellums. They include (1) fairy tales

properly so-called

— i.e., tales or anecdotes about fairies, hobgoblins,

&c., told

as natural occurrences; (2) hero-tales, stories of adventure told of

national or

mythical heroes; (3) folk-tales proper, describing marvellous

adventures of otherwise

unknown heroes, in which there is a defined plot and supernatural

characters (speaking

animals, giants, dwarfs, &c.); and finally (4) drolls, comic

anecdotes of feats

of stupidity or cunning. The

collection

of Celtic folk-tales began in IRELAND as early as 1825, with T. Crofton

Croker's

Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland. This

contained some

38 anecdotes of the first class mentioned above, anecdotes showing the

belief of

the Irish peasantry in the existence of fairies, gnomes, goblins, and

the like.

The Grimms did Croker the honour of translating part of his book, under

the title

of Irische Elfenmärchen. Among the novelists and tale-writers

of the schools

of Miss Edgeworth and Lever folk-tales were occasionally utilised, as

by Carleton

in his Traits and Stories, by S. Lover in his Legends and

Stories,

and by G. Griffin in his Tales of a Jury-Room. These all tell

their tales

in the manner of the stage Irishman. Chapbooks, Royal Fairy Tales

and Hibernian

Tales, also contained genuine folk-tales, and attracted Thackeray's

attention

in his Irish Sketch-Book. The Irish Grimm, however, was Patrick

Kennedy,

a Dublin bookseller, who believed in fairies, and in five years (1866-

71) printed

about 100 folk- and hero-tales and drolls (classes 2, 3, and 4 above)

in his Legendary

Fictions of the Irish Celts, 1866, Fireside Stories of Ireland,

1870,

and Bardic Stories of Ireland, 1871; all three are now

unfortunately out

of print. He tells his stories neatly and with spirit, and retains much

that is

volkstümlich in his diction. He derived his materials from

the English-speaking

peasantry of county Wexford, who changed from Gaelic to English while

story-telling

was in full vigour, and therefore carried over the stories with the

change of language.

Lady Wylde has told many folk-tales very effectively in her Ancient

Legends of

Ireland, 1887. More recently two collectors have published stories

gathered

from peasants of the West and North who can only speak Gaelic. These

are by an American

gentleman named Curtin, Myths and Folk-Tales of Ireland, 1890;

while Dr.

Douglas Hyde has published in Beside the Fireside, 1891,

spirited English

versions of some of the stories he had published in the original Irish

in his Leabhar

Sgeulaighteachta, Dublin, 1889. Miss Maclintoch has a large MS.

collection,

part of which has appeared in various periodicals; and Messrs. Larminie

and D. Fitzgerald

are known to have much story material in their possession. But beside

these more modern collections there exist in old and middle Irish a

large number

of hero-tales (class 2) which formed the staple of the old ollahms

or bards.

Of these tales of "cattle-liftings, elopements, battles, voyages,

courtships,

caves, lakes, feasts, sieges, and eruptions," a bard of even the fourth

class

had to know seven fifties, presumably one for each day of the year. Sir

William

Temple knew of a north-country gentleman of Ireland who was sent to

sleep every

evening with a fresh tale from his bard. The Book of Leinster,

an Irish vellum

of the twelfth century, contains a list of 189 of these hero-tales,

many of which

are extant to this day; E. O'Curry gives the list in the Appendix to

his MS. Materials

of Irish History. Another list of about 70 is given in the preface

to the third

volume of the Ossianic Society's publications. Dr. Joyce published a

few of the

more celebrated of these in Old Celtic Romances; others

appeared in Atlantis

(see notes on "Deirdre"), others in Kennedy's Bardic Stories,

mentioned

above. Turning

to SCOTLAND, we must put aside Chambers' Popular Rhymes of Scotland,

1842,

which contains for the most part folk-tales common with those of

England rather

than those peculiar to the Gaelic-speaking Scots. The first name here

in time as

in importance is that of J. F. Campbell, of Islay. His four volumes, Popular

Tales of the West Highlands (Edinburgh, 1860-2, recently

republished by the

Islay Association), contain some 120 folk- and hero-tales, told with

strict adherence

to the language of the narrators, which is given with a literal, a

rather too literal,

English version. This careful accuracy has given an un-English air to

his versions,

and has prevented them attaining their due popularity. What Campbell

has published

represents only a tithe of what he collected. At the end of the fourth

volume he

gives a list of 791 tales, &c., collected by him or his assistants

in the two

years 1859-61; and in his MS. collections at Edinburgh are two other

lists containing

400 more tales. Only a portion of these are in the Advocates' Library;

the rest,

if extant, must be in private hands, though they are distinctly of

national importance

and interest. Campbell's

influence has been effective of recent years in Scotland. The Celtic

Magazine

(vols. xii. and xiii.), while under the editorship of Mr. MacBain,

contained several

folk- and hero-tales in Gaelic, and so did the Scotch Celtic Review.

These

were from the collections of Messrs. Campbell of Tiree, Carmichael, and

K. Mackenzie.

Recently Lord Archibald Campbell has shown laudable interest in the

preservation

of Gaelic folk- and hero-tales. Under his auspices a whole series of

handsome volumes,

under the general title of Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition,

has been

recently published, four volumes having already appeared, each

accompanied by notes

by Mr. Alfred Nutt, which form the most important aid to the study of

Celtic Folk-Tales

since Campbell himself. Those to the second volume in particular (Tales

collected

by Rev. D. MacInnes) fill 100 pages, with condensed information on all

aspects of

the subject dealt with in the light of the most recent research in the

European

folk-tales as well as on Celtic literature. Thanks to Mr. Nutt,

Scotland is just

now to the fore in the collection and study of the British Folk-Tale. WALES

makes a poor show beside Ireland and Scotland. Sikes' British

Goblins, and

the tales collected by Prof. Rhys in Y Cymrodor, vols. ii.-vi.,

are mainly

of our first-class fairy anecdotes. Borrow, in his Wild Wales,

refers to

a collection of fables in a journal called The Greal, while the

Cambrian

Quarterly Magazine for 1830 and 1831 contained a few fairy

anecdotes, including

a curious version of the "Brewery of Eggshells" from the Welsh. In the

older literature, the Iolo MS., published by the Welsh MS.

Society, has a

few fables and apologues, and the charming Mabinogion,

translated by Lady

Guest, has tales that can trace back to the twelfth century and are on

the border-line

between folk-tales and hero-tales. CORNWALL

and MAN are even worse than Wales. Hunt's Drolls from the West of

England

has nothing distinctively Celtic, and it is only by a chance Lhuyd

chose a folk-tale

as his specimen of Cornish in his Archaeologia Britannica, 1709

(see Tale

of Ivan). The Manx folk-tales published, including the most recent

by Mr. Moore,

in his Folk-Lore of the Isle of Man, 1891, are mainly fairy

anecdotes and

legends. From this

survey of the field of Celtic folk-tales it is clear that Ireland and

Scotland provide

the lion's share. The interesting thing to notice is the remarkable

similarity of

Scotch and Irish folk-tales. The continuity of language and culture

between these

two divisions of Gaeldom has clearly brought about this identity of

their folk-tales.

As will be seen from the following notes, the tales found in Scotland

can almost

invariably be paralleled by those found in Ireland, and vice versa.

This

result is a striking confirmation of the general truth that folk-lores

of different

countries resemble one another in proportion to their contiguity and to

the continuity

of language and culture between them. Another

point of interest in these Celtic folk-tales is the light they throw

upon the relation

of hero-tales and folk-tales (classes 2 and 3 above). Tales told of

Finn of Cuchulain,

and therefore coming under the definition of hero-tales, are found

elsewhere told

of anonymous or unknown heroes. The question is, were the folk-tales

the earliest,

and were they localised and applied to the heroes, or were the heroic

sagas generalised

and applied to an unknown [Greek: tis]? All the evidence, in my

opinion, inclines

to the former view, which, as applied to Celtic folk-tales, is of very

great literary

importance; for it is becoming more and more recognised, thanks chiefly

to the admirable

work of Mr. Alfred Nutt, in his Studies on the Holy Grail, that

the outburst

of European Romance in the twelfth century was due, in large measure,

to an infusion

of Celtic hero-tales into the literature of the Romance-speaking

nations. Now the

remarkable thing is, how these hero tales have lingered on in oral

tradition even

to the present day. (See a marked case in "Deirdre.") We may,

therefore,

hope to see considerable light thrown on the most characteristic

spiritual product

of the Middle Ages, the literature of Romance and the spirit of

chivalry, from the

Celtic folk-tales of the present day. Mr. Alfred Nutt has already shown

this to

be true of a special section of Romance literature, that connected with

the Holy

Grail, and it seems probable that further study will extend the field

of application

of this new method of research. The Celtic

folk-tale again has interest in retaining many traits of primitive

conditions among

the early inhabitants of these isles which are preserved by no other

record. Take,

for instance, the calm assumption of polygamy in "Gold Tree and Silver

Tree."

That represents a state of feeling that is decidedly pre-Christian. The

belief in

an external soul "Life Index," recently monographed by Mr. Frazer in

his

"Golden Bough," also finds expression in a couple of the Tales (see

notes

on "Sea-Maiden" and "Fair, Brown, and Trembling"), and so with

many other primitive ideas. Care,

however, has to be taken in using folk-tales as evidence for primitive

practice

among the nations where they are found. For the tales may have come

from another

race — that is, for example, probably the case with "Gold Tree and

Silver Tree"

(see Notes). Celtic tales are of peculiar interest in this connection,

as they afford

one of the best fields for studying the problem of diffusion, the most

pressing

of the problems of the folk-tales just at present, at least in my

opinion. The Celts

are at the furthermost end of Europe. Tales that travelled to them

could go no further

and must therefore be the last links in the chain. For all

these reasons, then, Celtic folk-tales are of high scientific interest

to the folk-lorist,

while they yield to none in imaginative and literary qualities. In any

other country

of Europe some national means of recording them would have long ago

been adopted.

M. Luzel, e.g., was commissioned by the French Minister of

Public Instruction

to collect and report on the Breton folk-tales. England, here as

elsewhere without

any organised means of scientific research in the historical and

philological sciences,

has to depend on the enthusiasm of a few private individuals for work

of national

importance. Every Celt of these islands or in the Gaeldom beyond the

sea, and every

Celt-lover among the English-speaking nations, should regard it as one

of the duties

of the race to put its traditions on record in the few years that now

remain before

they will cease for ever to be living in the hearts and memories of the

humbler

members of the race. In the

following Notes I have done as in my English Fairy Tales, and

given first,

the sources whence I drew the tales, then parallels at

length for

the British Isles, with bibliographical references for parallels

abroad, and finally,

remarks where the tales seemed to need them. In these I

have not wearied

or worried the reader with conventional tall talk about the Celtic

genius and its

manifestations in the folk-tale; on that topic one can only repeat

Matthew Arnold

when at his best, in his Celtic Literature. Nor have I

attempted to deal

with the more general aspects of the study of the Celtic folk-tale. For

these I

must refer to Mr. Nutt's series of papers in The Celtic Magazine,

vol. xii.,

or, still better, to the masterly introductions he is contributing to

the series

of Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition, and to Dr. Hyde's Beside

the

Fireside. In my remarks I have mainly confined myself to discussing

the origin

and diffusion of the various tales, so far as anything definite could

be learnt

or conjectured on that subject. Before

proceeding to the Notes, I may "put in," as the lawyers say, a few

summaries

of the results reached in them. Of the twenty-six tales, twelve (i.,

ii., v., viii.,

ix., x., xi., xv., xvi., xvii., xix., xxiv.) have Gaelic originals;

three (vii.,

xiii., xxv.) are from the Welsh; one (xxii.) from the now extinct

Cornish; one an

adaptation of an English poem founded on a Welsh tradition (xxi.,

"Gellert");

and the remaining nine are what may be termed Anglo-Irish. Regarding

their diffusion

among the Celts, twelve are both Irish and Scotch (iv., v., vi., ix.,

x., xiv.-xvii.,

xix., xx., xxiv); one (xxv.) is common to Irish and Welsh; and one

(xxii.) to Irish

and Cornish; seven are found only among the Celts in Ireland (i.-iii.,

xii., xviii.,

xxii., xxvi); two (viii., xi.) among the Scotch; and three (vii.,

xiii., xxi.) among

the Welsh. Finally, so far as we can ascertain their origin, four (v.,

xvi., xxi.,

xxii.) are from the East; five (vi., x., xiv., xx., xxv.) are European

drolls; three

of the romantic tales seem to have been imported (vii., ix., xix.);

while three

others are possibly Celtic exportations to the Continent (xv., xvii.,

xxiv.) though

the, last may have previously come thence; the remaining eleven are, as

far as known,

original to Celtic lands. Somewhat the same result would come out, I

believe, as

the analysis of any representative collection of folk-tales of any

European district. I. CONNLA

AND THE FAIRY MAIDEN. Source. — From the

old Irish "Echtra Condla chaim maic Cuind Chetchathaig"

of the Leabhar na h-Uidhre ("Book of the Dun Cow"), which must

have been written before 1106, when its scribe Maelmori ("Servant of

Mary")

was murdered. The original is given by Windisch in his Irish Grammar,

p.

120, also in the Trans. Kilkenny Archaeol. Soc. for 1874. A

fragment occurs

in a Rawlinson MS., described by Dr. W. Stokes, Tripartite Life,

p. xxxvi.

I have used the translation of Prof. Zimmer in his Keltische

Beiträge, ii.

(Zeits. f. deutsches Altertum, Bd. xxxiii. 262-4). Dr. Joyce has

a somewhat

florid version in, his Old Celtic Romances, from which I have

borrowed a

touch or two. I have neither extenuated nor added aught but the last

sentence of

the Fairy Maiden's last speech. Part of the original is in metrical

form, so that

the whole is of the cante-fable species which I believe to be

the original

form of the folk-tale (Cf. Eng. Fairy Tales, notes, p. 240, and

infra,

p. 257). Parallels. — Prof.

Zimmer's paper contains three other accounts of the

terra repromissionis in the Irish sagas, one of them being

the similar adventure

of Cormac the nephew of Connla, or Condla Ruad as he should be called.

The fairy

apple of gold occurs in Cormac Mac Art's visit to the Brug of Manannan

(Nutt's Holy

Grail, 193). Remarks. — Conn the

hundred-fighter had the head-kingship of Ireland

123-157 A.D., according to the Annals of the Four Masters, i.

105. On the

day of his birth the five great roads from Tara to all parts of Ireland

were completed:

one of them from Dublin is still used. Connaught is said to have been

named after

him, but this is scarcely consonant with Joyce's identification with

Ptolemy's Nagnatai

(Irish Local Names, i. 75). But there can be little doubt of

Conn's existence

as a powerful ruler in Ireland in the second century. The historic

existence of

Connla seems also to be authenticated by the reference to him as Conly,

the eldest

son of Conn, in the Annals of Clonmacnoise. As Conn was succeeded by

his third son,

Art Enear, Connla was either slain or disappeared during his father's

lifetime.

Under these circumstances it is not unlikely that our legend grew up

within the

century after Conn — i.e., during the latter half of the second

century. As regards

the present form of it, Prof. Zimmer (l.c. 261-2) places it in

the seventh

century. It has clearly been touched up by a Christian hand who

introduced the reference

to the day of judgment and to the waning power of the Druids. But

nothing turns

upon this interpolation, so that it is likely that even the present

form of the

legend is pre-Christian-i.e. for Ireland, pre-Patrician, before

the fifth

century. The tale

of Connla is thus the earliest fairy tale of modern Europe. Besides

this interest

it contains an early account of one of the most characteristic Celtic

conceptions,

that of the earthly Paradise, the Isle of Youth, Tir-nan-Og.

This has impressed

itself on the European imagination; in the Arthuriad it is represented

by the Vale

of Avalon, and as represented in the various Celtic visions of the

future life,

it forms one of the main sources of Dante's Divina Commedia. It

is possible

too, I think, that the Homeric Hesperides and the Fortunate Isles of

the ancients

had a Celtic origin (as is well known, the early place-names of Europe

are predominantly

Celtic). I have found, I believe, a reference to the conception in one

of the earliest

passages in the classics dealing with the Druids. Lucan, in his Pharsalia

(i. 450-8), addresses them in these high terms of reverence: Et vos barbaricos ritus, moremque sinistrum, Sacrorum, Druidae, positis repetistis ab armis, Solis nosse Deos et coeli numera vobis Aut solis nescire datum; nemora alta remotis Incolitis lucis. Vobis auctoribus umbrae, Non tacitas Erebi sedes, Ditisque profundi, Pallida regna petunt: regit idem spiritus artus Orbe alio: longae, canitis si cognita, vitae Mors media est. The passage

certainly seems to me to imply a different conception from the ordinary

classical

views of the life after death, the dark and dismal plains of Erebus

peopled with

ghosts; and the passage I have italicised would chime in well with the

conception

of a continuance of youth (idem spiritus) in Tir-nan-Og (orbe

alio). One of

the most pathetic, beautiful, and typical scenes in Irish legend is the

return of

Ossian from Tir-nan-Og, and his interview with St. Patrick. The old

faith and the

new, the old order of things and that which replaced it, meet in two of

the most

characteristic products of the Irish imagination (for the Patrick of

legend is as

much a legendary figure as Oisin himself). Ossian had gone away to

Tir-nan-Og with

the fairy Niamh under very much the same circumstances as Condla Ruad;

time flies

in the land of eternal youth, and when Ossian returns, after a year as

he thinks,

more than three centuries had passed, and St. Patrick had just

succeeded in introducing

the new faith. The contrast of Past and Present has never been more

vividly or beautifully

represented. II. GULEESH. Source. — From Dr.

Douglas Hyde's Beside the Fire, 104-28, where

it is a translation from the same author's Leabhar Sgeulaighteachta.

Dr Hyde

got it from one Shamus O'Hart, a gamekeeper of Frenchpark. One is

curious to know

how far the very beautiful landscapes in the story are due to Dr. Hyde,

who confesses

to have only taken notes. I have omitted a journey to Rome, paralleled,

as Mr. Nutt

has pointed out, by the similar one of Michael Scott (Waifs and

Strays, i.

46), and not bearing on the main lines of the story. I have also

dropped a part

of Guleesh's name: in the original he is "Guleesh na guss dhu," Guleesh

of the black feet, because he never washed them; nothing turns on this

in the present

form of the story, but one cannot but suspect it was of importance in

the original

form. Parallels. — Dr. Hyde

refers to two short stories, "Midnight Ride"

(to Rome) and "Stolen Bride," in Lady Wilde's Ancient Legends.

But the closest parallel is given by Miss Maclintock's Donegal tale of

"Jamie

Freel and the Young Lady," reprinted in Mr. Yeats' Irish Folk and

Fairy

Tales, 52-9. In the Hibernian Tales, "Mann o' Malaghan and

the Fairies,"

as reported by Thackeray in the Irish Sketch-Book, c. xvi.,

begins like "Guleesh." III. FIELD

OF BOLIAUNS. Source. — T.

Crofton Croker's Fairy Legends of the South of Ireland,

ed. Wright, pp. 135-9. In the original the gnome is a Cluricaune, but

as a friend

of Mr. Batten's has recently heard the tale told of a Lepracaun, I have

adopted

the better known title. Remarks. — Lepracaun

is from the Irish leith bhrogan,

the one-shoemaker (cf. brogue), according to Dr. Hyde. He is

generally seen

(and to this day, too) working at a single shoe, cf. Croker's

story "Little

Shoe," l.c. pp. 142-4. According to a writer in the Revue

Celtique,

i. 256, the true etymology is luchor pan, "little man." Dr.

Joyce

also gives the same etymology in Irish Names and Places, i.

183, where he

mentions several places named after them. IV. HORNED

WOMEN. Source. — Lady

Wilde's Ancient Legends, the first story. Parallels. — A

similar version was given by Mr. D. Fitzgerald in the Revue

Celtique, iv. 181, but without the significant and impressive

horns. He refers

to Cornhill for February 1877, and to Campbell's "Sauntraigh"

No.

xxii. Pop. Tales, ii. 52 4, in which a "woman of peace" (a

fairy)

borrows a woman's kettle and returns it with flesh in it, but at last

the woman

refuses, and is persecuted by the fairy. I fail to see much analogy. A

much closer

one is in Campbell, ii. p. 63, where fairies are got rid of by shouting

"Dunveilg

is on fire." The familiar "lady-bird, lady-bird, fly away home, your

house

is on fire and your children at home," will occur to English minds.

Another

version in Kennedy's Legendary Fictions, p. 164, "Black Stairs

on Fire." Remarks. —

Slievenamon is a famous fairy palace in Tipperary according

to Dr. Joyce, l.c. i. 178. It was the hill on which Finn stood

when he gave

himself as the prize to the Irish maiden who should run up it quickest.

Grainne

won him with dire consequences, as all the world knows or ought to know

(Kennedy,

Legend Fict., 222, "How Fion selected a Wife"). V. CONAL

YELLOWCLAW. Source. —

Campbell, Pop. Tales of West Highlands, No. v. pp.

105-8, "Conall Cra Bhuidhe." I have softened the third episode, which

is somewhat too ghastly in the original. I have translated "Cra Bhuide"

Yellowclaw on the strength of Campbell's etymology, l.c. p. 158. Parallels. —

Campbell's vi. and vii. are two variants showing how widespread

the story is in Gaelic Scotland. It occurs in Ireland where it has been

printed

in the chapbook, Hibernian Tales, as the "Black Thief and the

Knight

of the Glen," the Black Thief being Conall, and the knight

corresponding to

the King of Lochlan (it is given in Mr. Lang's Red Fairy Book).

Here it attracted

the notice of Thackeray, who gives a good abstract of it in his Irish

Sketch-Book,

ch. xvi. He thinks it "worthy of the Arabian Nights, as wild and odd as

an

Eastern tale." "That fantastical way of bearing testimony to the

previous

tale by producing an old woman who says the tale is not only true, but

who was the

very old woman who lived in the giant's castle is almost" (why

"almost,"

Mr. Thackeray?) "a stroke of genius." The incident of the giant's

breath

occurs in the story of Koisha Kayn, MacInnes' Tales, i. 241, as

well as the

Polyphemus one, ibid. 265. One-eyed giants are frequent in

Celtic folk-tales

(e.g. in The Pursuit of Diarmaid and in the Mabinogi

of Owen). Remarks. —

Thackeray's reference to the "Arabian Nights" is

especially apt, as the tale of Conall is a framework story like The

1001 Nights,

the three stories told by Conall being framed, as it were, in a fourth

which is

nominally the real story. This method employed by the Indian

story-tellers and from

them adopted by Boccaccio and thence into all European literatures

(Chaucer, Queen

Margaret, &c.), is generally thought to be peculiar to the East,

and to be ultimately

derived from the Jatakas or Birth Stories of the Buddha who tells his

adventures

in former incarnations. Here we find it in Celtdom, and it occurs also

in "The

Story-teller at Fault" in this collection, and the story of Koisha

Kayn

in MacInnes' Argyllshire Tales, a variant of which, collected

but not published

by Campbell, has no less than nineteen tales enclosed in a framework.

The question

is whether the method was adopted independently in Ireland, or was due

to foreign

influences. Confining ourselves to "Conal Yellowclaw," it seems not

unlikely

that the whole story is an importation. For the second episode is

clearly the story

of Polyphemus from the Odyssey which was known in Ireland perhaps as

early as the

tenth century (see Prof. K. Meyer's edition of Merugud Uilix maic

Leirtis,

Pref. p. xii). It also crept into the voyages of Sindbad in the Arabian

Nights.

And as told in the Highlands it bears comparison even with the Homeric

version.

As Mr. Nutt remarks (Celt. Mag. xii.) the address of the giant

to the buck

is as effective as that of Polyphemus to his ram. The narrator, James

Wilson, was

a blind man who would naturally feel the pathos of the address; "it

comes from

the heart of the narrator;" says Campbell (l.c., 148), "it is

the

ornament which his mind hangs on the frame of the story." VI. HUDDEN

AND DUDDEN. Source. — From oral

tradition, by the late D. W. Logie, taken down by

Mr. Alfred Nutt. Parallels. — Lover has

a tale, "Little Fairly," obviously derived

from this folk-tale; and there is another very similar, "Darby Darly."

Another version of our tale is given under the title "Donald and his

Neighbours,"

in the chapbook Hibernian Tales, whence it was reprinted by

Thackeray in

his Irish Sketch-Book, c. xvi. This has the incident of the

"accidental

matricide," on which see Prof. R. Köhler on Gonzenbach Sicil.

Mährchen,

ii. 224. No less than four tales of Campbell are of this type (Pop.

Tales,

ii. 218-31). M. Cosquin, in his "Contes populaires de Lorraine," the

storehouse

of "storiology," has elaborate excursuses in this class of tales

attached

to his Nos. x. and xx. Mr. Clouston discusses it also in his Pop.

Tales,

ii. 229-88. Both these writers are inclined to trace the chief

incidents to India.

It is to be observed that one of the earliest popular drolls in Europe,

Unibos,

a Latin poem of the eleventh, and perhaps the tenth, century, has the

main outlines

of the story, the fraudulent sale of worthless objects and the escape

from the sack

trick. The same story occurs in Straparola, the European earliest

collection of

folk-tales in the sixteenth century. On the other hand, the gold

sticking to the

scales is familiar to us in Ali Baba. (Cf. Cosquin, l.c.,

i.

225-6, 229). Remarks. — It is

indeed curious to find, as M. Cosquin points out, a

cunning fellow tied in a sack getting out by crying, "I won't marry the

princess,"

in countries so far apart as Ireland, Sicily (Gonzenbach, No. 71),

Afghanistan (Thorburn,

Bannu, p. 184), and Jamaica (Folk-Lore Record, iii.

53). It is indeed

impossible to think these are disconnected, and for drolls of this kind

a good case

has been made out for the borrowing hypotheses by M. Cosquin and Mr.

Clouston. Who

borrowed from whom is another and more difficult question which has to

be judged

on its merits in each individual case. This is

a type of Celtic folk-tales which are European in spread, have

analogies with the

East, and can only be said to be Celtic by adoption and by colouring.

They form

a distinct section of the tales told by the Celts, and must be

represented in any

characteristic selection. Other examples are xi., xv., xx., and perhaps

xxii. VII.

SHEPHERD OF MYDDVAI. Source. — Preface

to the edition of "The Physicians of Myddvai";

their prescription-book, from the Red Book of Hergest, published by the

Welsh MS.

Society in 1861. The legend is not given in the Red Book, but from oral

tradition

by Mr. W. Rees, p. xxi. As this is the first of the Welsh tales in this

book it

may be as well to give the reader such guidance as I can afford him on

the intricacies

of Welsh pronunciation, especially with regard to the mysterious w's

and

y's of Welsh orthography. For w substitute double o,

as in

"fool," and for y, the short u in but,

and

as near approach to Cymric speech will be reached as is possible for

the outlander.

It maybe added that double d equals th, and double l

is something

like Fl, as Shakespeare knew in calling his Welsh soldier

Fluellen (Llewelyn).

Thus "Meddygon Myddvai" would be Anglicè "Methugon Muthvai." Parallels. — Other

versions of the legend of the Van Pool are given in

Cambro-Briton, ii. 315; W. Sikes, British Goblins,

p. 40. Mr. E. Sidney

Hartland has discussed these and others in a set of papers contributed

to the first

volume of The Archaeological Review (now incorporated into Folk-Lore),

the substance of which is now given in his Science of Fairy Tales,

274-332.

(See also the references given in Revue Celtique, iv., 187 and

268). Mr.

Hartland gives there an ecumenical collection of parallels to the

several incidents

that go to make up our story — (1) The bride-capture of the

Swan-Maiden, (2) the

recognition of the bride, (3) the taboo against causeless blows, (4)

doomed to be

broken, and (5) disappearance of the Swan-Maiden, with (6) her return

as Guardian

Spirit to her descendants. In each case Mr. Hartland gives what he

considers to

be the most primitive form of the incident. With reference to our

present tale,

he comes to the conclusion, if I understand him aright, that the

lake-maiden was

once regarded as a local divinity. The physicians of Myddvai were

historic personages,

renowned for their medical skill for some six centuries, till the race

died out

with John Jones, fl. 1743. To explain their skill and uncanny

knowledge of

herbs, the folk traced them to a supernatural ancestress, who taught

them their

craft in a place still called Pant-y-Meddygon ("Doctors' Dingle").

Their

medical knowledge did not require any such remarkable origin, as Mr.

Hartland has

shown in a paper "On Welsh Folk-Medicine," contributed to Y

Cymmrodor,

vol. xii. On the other hand, the Swan-Maiden type of story is

widespread through

the Old World. Mr. Morris' "Land East of the Moon and West of the Sun,"

in The Earthly Paradise, is taken from the Norse version.

Parallels are accumulated

by the Grimms, ii. 432; Köhler on Gonzenbach, ii. 20; or Blade, 149;

Stokes' Indian

Fairy Tales, 243, 276; and Messrs. Jones and Koopf, Magyar

Folk-Tales,

362-5. It remains to be proved that one of these versions did not

travel to Wales,

and become there localised. We shall see other instances of such

localisation or

specialisation of general legends. VIII. THE

SPRIGHTLY TAILOR. Source. — Notes

and Queries for December 21, 1861; to which it

was communicated by "Cuthbert Bede," the author of Verdant Green,

who collected it in Cantyre. Parallels. — Miss

Dempster gives the same story in her Sutherland Collection,

No. vii. (referred to by Campbell in his Gaelic list, at end of vol.

iv.); Mrs.

John Faed, I am informed by a friend, knows the Gaelic version, as told

by her nurse

in her youth. Chambers' "Strange Visitor," Pop. Rhymes of Scotland,

64, of which I gave an Anglicised version in my English Fairy Tales,

No.

xxxii., is clearly a variant. Remarks. — The

Macdonald of Saddell Castle was a very great man indeed.

Once, when dining with the Lord-Lieutenant, an apology was made to him

for placing

him so far away from the head of the table. "Where the Macdonald sits,"

was the proud response, "there is the head of the table." IX. DEIRDRE. Source. — Celtic

Magazine, xiii. pp. 69, seq. I have

abridged somewhat, made the sons of Fergus all faithful instead of two

traitors,

and omitted an incident in the house of the wild men called here

"strangers."

The original Gaelic was given in the Transactions of the Inverness

Gaelic Society

for 1887, p. 241, seq., by Mr. Carmichael. I have inserted

Deirdre's "Lament"

from the Book of Leinster. Parallels. — This is

one of the three most sorrowful Tales of Erin, (the

other two, Children of Lir and Children of Tureen, are

given in Dr.

Joyce's Old Celtic Romances), and is a specimen of the old

heroic sagas of

elopement, a list of which is given in the Book of Leinster.

The "outcast

child" is a frequent episode in folk and hero-tales: an instance occurs

in

my English Fairy Tales, No. xxxv., and Prof. Köhler gives many

others in

Archiv. f. Slav. Philologie, i. 288. Mr. Nutt adds tenth

century Celtic parallels

in Folk-Lore, vol. ii. The wooing of hero by heroine is a

characteristic

Celtic touch. See "Connla" here, and other examples given by Mr. Nutt

in his notes to MacInnes' Tales. The trees growing from the

lovers' graves

occurs in the English ballad of Lord Lovel and has been studied

in Mélusine. Remarks. — The

"Story of Deirdre" is a remarkable instance

of the tenacity of oral tradition among the Celts. It has been

preserved in no less

than five versions (or six, including Macpherson's "Darthula") ranging

from the twelfth to the nineteenth century. The earliest is in the

twelfth century,

Book of Leinster, to be dated about 1140 (edited in

facsimile under the auspices

of the Royal Irish Academy, i. 147, seq.). Then comes a

fifteenth century

version, edited and translated by Dr. Stokes in Windisch's Irische

Texte

II., ii. 109, seq., "Death of the Sons of Uisnech." Keating in

his History of Ireland gave another version in the seventeenth

century. The

Dublin Gaelic Society published an eighteenth century version in their Transactions

for 1808. And lastly we have the version before us, collected only a

few years ago,

yet agreeing in all essential details with the version of the Book

of Leinster.

Such a record is unique in the history of oral tradition, outside

Ireland, where,

however, it is quite a customary experience in the study of the

Finn-saga. It is

now recognised that Macpherson had, or could have had, ample material

for his rechauffé

of the Finn or "Fingal" saga. His "Darthula" is a similar cobbling

of our present story. I leave to Celtic specialists the task of

settling the exact

relations of these various texts. I content myself with pointing out

the fact that

in these latter days of a seemingly prosaic century in these British

Isles there

has been collected from the lips of the folk a heroic story like this

of "Deirdre,"

full of romantic incidents, told with tender feeling and considerable

literary skill.

No other country in Europe, except perhaps Russia, could provide a

parallel to this

living on of Romance among the common folk. Surely it is a bounden duty

of those

who are in the position to put on record any such utterances of the

folk-imagination

of the Celts before it is too late. X. MUNACHAR

AND MANACHAR. Source. — I have

combined the Irish version given by Dr. Hyde in his

Leabhar Sgeul., and translated by him for Mr. Yeats' Irish

Folk and Fairy

Tales, and the Scotch version given in Gaelic and English by

Campbell, No. viii. Parallels. — Two

English versions are given in my Eng. Fairy Tales,

No. iv., "The Old Woman and her Pig," and xxxiv., "The Cat and the

Mouse," where see notes for other variants in these isles. M. Cosquin,

in his

notes to No. xxxiv., of his Contes de Lorraine, t. ii. pp.

35-41, has drawn

attention to an astonishing number of parallels scattered through all

Europe and

the East (cf., too, Crane, Ital. Pop. Tales, notes,

372-5). One of

the earliest allusions to the jingle is in Don Quixote, pt. 1,

c. xvi.: "Y

asi como suele decirse el gato al rato, et rato á la cuerda, la

cuerda al palo,

daba el arriero á Sancho, Sancho á la moza, la moza á él, el ventero á

la moza."

As I have pointed out, it is used to this day by Bengali women at the

end of each

folk-tale they recite (L. B. Day, Folk-Tales of Bengal, Pref.). Remarks. — Two

ingenious suggestions have been made as to the origin

of this curious jingle, both connecting it with religious ceremonies:

(1) Something

very similar occurs in Chaldaic at the end of the Jewish Hagada,

or domestic

ritual for the Passover night. It has, however, been shown that this

does not occur

in early MSS. or editions, and was only added at the end to amuse the

children after

the service, and was therefore only a translation or adaptation of a

current German

form of the jingle; (2) M. Basset, in the Revue des Traditions

populaires,

1890, t. v. p. 549, has suggested that it is a survival of the old

Greek custom

at the sacrifice of the Bouphonia for the priest to contend that he

had not

slain the sacred beast, the axe declares that the handle did it, the

handle transfers

the guilt further, and so on. This is ingenious, but fails to give any

reasonable

account of the diffusion of the jingle in countries which have had no

historic connection

with classical Greece. XI. GOLD

TREE AND SILVER TREE. Source. — Celtic

Magazine, xiii. 213-8, Gaelic and English from

Mr. Kenneth Macleod. Parallels. — Mr.

Macleod heard another version in which "Gold Tree"

(anonymous in this variant) is bewitched to kill her father's horse,

dog, and cock.

Abroad it is the Grimm's Schneewittchen (No. 53), for the

Continental variants

of which see Köhler on Gonzenbach, Sicil. Mährchen, Nos. 2-4,

Grimm's notes

on 53, and Crane, Ital. Pop. Tales, 331. No other version is

known in the

British Isles. Remarks. — It is

unlikely, I should say impossible, that this tale,

with the incident of the dormant heroine, should have arisen

independently in the

Highlands; it is most likely an importation from abroad. Yet in it

occurs a most

"primitive" incident, the bigamous household of the hero; this is

glossed

over in Mr. Macleod's other variant. On the "survival" method of

investigation

this would possibly be used as evidence for polygamy in the Highlands.

Yet if, as

is probable, the story came from abroad, this trait may have come with

it, and only

implies polygamy in the original home of the tale. XII. KING

O'TOOLE AND HIS GOOSE. Source. — S.

Lover's Stories and Legends of the Irish Peasantry. Remarks. — This is

really a moral apologue on the benefits of keeping

your word. Yet it is told with such humour and vigour, that the moral

glides insensibly

into the heart. XIII. THE

WOOING OF OLWEN. Source. — The Mabinogi

of Kulhwych and Olwen from the translation

of Lady Guest, abridged. Parallels. — Prof.

Rhys, Hibbert Lectures, p. 486, considers that

our tale is paralleled by Cuchulain's "Wooing of Emer," a translation

of which by Prof. K. Meyer appeared in the Archaeological Review,

vol. i.

I fail to see much analogy. On the other hand in his Arthurian

Legend, p.

41, he rightly compares the tasks set by Yspythadon to those set to

Jason. They

are indeed of the familiar type of the Bride Wager (on which see

Grimm-Hunt, i.

399). The incident of the three animals, old, older, and oldest, has a

remarkable

resemblance to the Tettira Jataka (ed. Fausböll, No. 37,

transl. Rhys Davids,

i. p. 310 seq.) in which the partridge, monkey, and elephant

dispute as to

their relative age, and the partridge turns out to have voided the seed

of the Banyan-tree

under which they were sheltered, whereas the elephant only knew it when

a mere bush,

and the monkey had nibbled the topmost shoots. This apologue got to

England at the

end of the twelfth century as the sixty-ninth fable, "Wolf, Fox, and

Dove,"

of a rhymed prose collection of "Fox Fables" (Mishle Shu'alim),

of an Oxford Jew, Berachyah Nakdan, known in the Records as "Benedict

le Puncteur"

(see my Fables Of Aesop, i. p. 170). Similar incidents occur in

"Jack

and his Snuff-box" in my English Fairy Tales, and in Dr. Hyde's

"Well

of D'Yerree-in-Dowan." The skilled companions of Kulhwych are common in

European

folk-tales (Cf. Cosquin, i. 123-5), and especially among the

Celts (see Mr.

Nutt's note in MacInnes' Tales, 445-8), among whom they occur

very early,

but not so early as Lynceus and the other skilled comrades of the

Argonauts.  Remarks. — The

hunting of the boar Trwyth can be traced back in Welsh

tradition at least as early as the ninth century. For it is referred to

in the following

passage of Nennius' Historia Britonum ed. Stevenson, p: 60,

"Est aliud

miraculum in regione quae dicitur Buelt [Builth, co. Brecon] Est ibi

cumulus lapidum

et unus lapis super-positus super congestum cum vestigia canis in eo.

Quando venatus

est porcum Troynt [var. lec. Troit] impressit Cabal, qui erat

canis Arthuri

militis, vestigium in lapide et Arthur postea congregavit congestum

lapidum sub

lapide in quo erat vestigium canis sui et vocatur Carn Cabal."

Curiously enough

there is still a mountain called Carn Cabal in the district of Builth,

south of

Rhayader Gwy in Breconshire. Still more curiously a friend of Lady

Guest's found

on this a cairn with a stone two feet long by one foot wide in which

there was an

indentation 4 in. x 3 in. x 2 in. which could easily have been mistaken

for a paw-print

of a dog, as maybe seen from the engraving given of it (Mabinogion, ed.

1874, p.

269). The stone

and the legend are thus at least one thousand years old. "There stands

the

stone to tell if I lie." According to Prof. Rhys (Hibbert Lect.

486-97)

the whole story is a mythological one, Kulhwych's mother being the

dawn, the clover

blossoms that grow under Olwen's feet being comparable to the roses

that sprung

up where Aphrodite had trod, and Yspyddadon being the incarnation of

the sacred

hawthorn. Mabon, again (i.e. pp. 21, 28-9), is the Apollo

Maponus discovered

in Latin inscriptions at Ainstable in Cumberland and elsewhere (Hübner,

Corp.

Insc. Lat. Brit. Nos. 218, 332, 1345). Granting all this, there is

nothing to

show any mythological significance in the tale, though there may have

been in the

names of the dramatis personae. I observe from the proceedings

of the recent

Eisteddfod that the bardic name of Mr. W. Abraham, M.P., is 'Mabon.' It

scarcely

follows that Mr. Abraham is in receipt of divine honours nowadays. XIV. JACK

AND HIS COMRADES. Source. —

Kennedy's Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts. Parallels. — This is

the fullest and most dramatic version I know of the

Grimm's "Town Musicians of Bremen" (No. 27). I have given an English

(American)

version in my English Fairy Tales, No. 5, in the notes to which

would be

found references to other versions known in the British Isles (e.g.,

Campbell,

No. 11) and abroad. Cf. remarks on No. vi. XV. SHEE AN

GANNON AND GRUAGACH GAIRE. Source. — Curtin, Myths

and Folk-Lore of Ireland, p. 114 seq.

I have shortened the earlier part of the tale, and introduced into the

latter a

few touches from Campbell's story of "Fionn's Enchantment," in Revue

Celtique, t. i., 193 seq. Parallels. — The

early part is similar to the beginning of "The Sea-Maiden"

(No. xvii., which see). The latter part is practically the same as the

story of

"Fionn's Enchantment," just referred to. It also occurs in MacInnes' Tales,

No. iii., "The King of Albainn" (see Mr. Nutt's notes, 454). The

head-crowned

spikes are Celtic, cf. Mr. Nutt's notes (MacInnes' Tales,

453). Remarks. — Here

again we meet the question whether the folk-tale precedes

the hero-tale about Finn or was derived from it, and again the

probability seems

that our story has the priority as a folk-tale, and was afterwards

applied to the

national hero, Finn. This is confirmed by the fact that a thirteenth

century French

romance, Conte du Graal, has much the same incidents, and was

probably derived

from a similar folk-tale of the Celts. Indeed, Mr. Nutt is inclined to

think that

the original form of our story (which contains a mysterious healing

vessel) is the

germ out of which the legend of the Holy Grail was evolved (see his Studies

in

the Holy Grail, p. 202 seq.). XVI. THE

STORY-TELLER AT FAULT. Source. —

Griffin's Tales from a Jury-Room, combined with Campbell,

No. xvii. c, "The Slim Swarthy Champion." Parallels. — Campbell

gives another variant, l.c. i. 318. Dr. Hyde

has an Irish version of Campbell's tale written down in 1762, from

which he gives

the incident of the air-ladder (which I have had to euphemise in my

version) in

his Beside the Fireside, p. 191, and other passages in his

Preface. The most

remarkable parallel to this incident, however, is afforded by the feats

of Indian

jugglers reported briefly by Marco Polo, and illustrated with his usual

wealth of

learning by the late Sir Henry Yule, in his edition, vol. i. p. 308 seq.

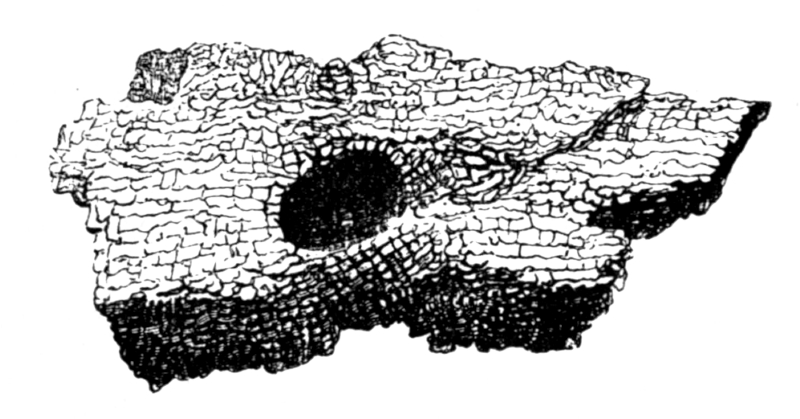

The accompanying illustration (reduced from Yule) will tell its own

tale: it is

taken from the Dutch account of the travels of an English sailor, E.

Melton, Zeldzaame

Reizen, 1702, p. 468. It tells the tale in five acts, all included

in one sketch.

Another instance quoted by Yule is still more parallel, so to speak.

The twenty-third

trick performed by some conjurors before the Emperor Jahangueir (Memoirs,

p. 102) is thus described: "They produced a chain of 50 cubits in

length, and

in my presence threw one end of it towards the sky, where it remained

as if fastened

to something in the air. A dog was then brought forward, and being

placed at the

lower end of the chain, immediately ran up, and, reaching the other

end, immediately

disappeared in the air. In the same manner a hog, a panther, a lion,

and a tiger

were successively sent up the chain." It has been suggested that the

conjurors

hypnotise the spectators, and make them believe they see these things.

This is practically

the suggestion of a wise Mohammedan, who is quoted by Yule as saying, "Wallah!

'tis my opinion there has been neither going up nor coming down; 'tis

all hocus-pocus,"

hocus-pocus being presumably the Mohammedan term for hypnotism.  Remarks. — Dr. Hyde

(l.c. Pref. xxix.) thinks our tale cannot

be older than 1362, because of a reference to one O'Connor Sligo which

occurs in

all its variants; it is, however, omitted in our somewhat abridged

version. Mr Nutt

(ap. Campbell, The Fians, Introd. xix.) thinks that this

does not

prevent a still earlier version having existed. I should have thought

that the existence

of so distinctly Eastern a trick in the tale, and the fact that it is a

framework

story (another Eastern characteristic), would imply that it is a rather

late importation,

with local allusions superadded (cf. notes on "Conal

Yellowclaw,"

No v.) The passages

in verse from pp 137, 139, and the description of the Beggarman, pp.

136, 140, are

instances of a curious characteristic of Gaelic folk-tales called

"runs."

Collections of conventional epithets are used over and over again to

describe the

same incident, the beaching of a boat, sea-faring, travelling and the

like, and

are inserted in different tales. These "runs" are often similar in both

the Irish and the Scotch form of the same tale or of the same incident.

The volumes

of Waifs and Strays contain numerous examples of these "runs,"

which have been indexed in each volume. These "runs" are another

confirmation

of my view that the original form of the folk-tale was that of the Cante-fable

(see note on "Connla" and on "Childe Rowland" in English

Fairy Tales). XVII.

SEA-MAIDEN. Source. —

Campbell, Pop. Tales, No. 4. I have omitted the births

of the animal comrades and transposed the carlin to the middle of the

tale. Mr.

Batten has considerately idealised the Sea-Maiden in his frontispiece.

When she

restores the husband to the wife in one of the variants, she brings him

out of her

mouth! "So the sea-maiden put up his head (Who do you mean? Out of

her mouth

to be sure. She had swallowed him)." Parallels. — The

early part of the story occurs in No. xv., "Shee

an Gannon," and the last part in No. xix., "Fair, Brown, and Trembling"

(both from Curtin), Campbell's No. 1. "The Young King" is much like it;

also MacInnes' No. iv., "Herding of Cruachan" and No. viii., "Lod

the Farmer's Son." The third of Mr. Britten's Irish folk-tales in the Folk-Lore

Journal is a Sea-Maiden story. The story is obviously a favourite

one among

the Celts. Yet its main incidents occur with frequency in Continental

folk-tales.

Prof. Köhler has collected a number in his notes on Campbell's Tales in

Orient

und Occident, Bnd. ii. 115-8. The trial of the sword occurs in the

saga of Sigurd,

yet it is also frequent in Celtic saga and folk-tales (see Mr. Nutt's

note, MacInnes'

Tales, 473, and add. Curtin, 320). The hideous carlin and

her three giant

sons is also a common form in Celtic. The external soul of the

Sea-Maiden carried

about in an egg, in a trout, in a hoodie, in a hind, is a remarkable

instance of

a peculiarly savage conception which has been studied by Major Temple, Wide-awake

Stories, 404-5; by Mr. E. Clodd, in the "Philosophy of Punchkin,"

in Folk-Lore Journal, vol. ii., and by Mr. Frazer in his Golden

Bough,

vol. ii. Remarks. — As both

Prof. Rhys (Hibbert Lect., 464) and Mr. Nutt

(MacInnes' Tales, 477) have pointed out, practically the same

story (that

of Perseus and Andromeda) is told of the Ultonian hero, Cuchulain, in

the Wooing

of Emer, a tale which occurs in the Book of Leinster, a MS. of the

twelfth century,

and was probably copied from one of the eighth. Unfortunately it is not

complete,

and the Sea-Maiden incident is only to be found in a British Museum MS.

of about

1300. In this Cuchulain finds that the daughter of Ruad is to be given

as a tribute

to the Fomori, who, according to Prof. Rhys, Folk-Lore, ii.

293, have something

of the nightmare about their etymology. Cuchulain fights three

of

them successively, has his wounds bound up by a strip of the maiden's

garment, and

then departs. Thereafter many boasted of having slain the Fomori, but

the maiden

believed them not till at last by a stratagem she recognises Cuchulain.

I may add

to this that in Mr. Curtin's Myths, 330, the threefold trial of

the sword

is told of Cuchulain. This would seem to trace our story back to the

seventh or

eighth century and certainly to the thirteenth. If so, it is likely

enough that

it spread from Ireland through Europe with the Irish missions (for the

wide extent

of which see map in Mrs. Bryant's Celtic Ireland). The very

letters that

have spread through all Europe except Russia, are to be traced to the

script of

these Irish monks: why not certain folk-tales? There is a further

question whether

the story was originally told of Cuchulain as a hero-tale and then

became departicularised

as a folk-tale, or was the process vice versa. Certainly in the

form in which

it appears in the Tochmarc Emer it is not complete, so that

here, as elsewhere,

we seem to have an instance of a folk-tale applied to a well-known

heroic name,

and becoming a hero-tale or saga. XVIII.

LEGEND OF KNOCKMANY. Source. — W.

Carleton, Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry. Parallels. —

Kennedy's "Fion MacCuil and the Scotch Giant,"

Legend. Fict., 203-5. Remarks. — Though

the venerable names of Finn and Cucullin (Cuchulain)

are attached to the heroes of this story, this is probably only to give

an extrinsic

interest to it. The two heroes could not have come together in any

early form of

their sagas, since Cuchulain's reputed date is of the first, Finn's of

the third

century A.D. (cf. however, MacDougall's Tales, notes,

272). Besides,

the grotesque form of the legend is enough to remove it from the region

of the hero-tale.

On the other hand, there is a distinct reference to Finn's

wisdom-tooth, which presaged

the future to him (on this see Revue Celtique, v. 201, Joyce, Old

Celt.

Rom., 434-5, and MacDougall, l.c. 274). Cucullin's

power-finger is another

instance of the life-index or external soul, on which see remarks on

Sea-Maiden.

Mr. Nutt informs me that parodies of the Irish sagas occur as early as

the sixteenth

century, and the present tale may be regarded as a specimen. XIX. FAIR,

BROWN, AND TREMBLING. Source. — Curtin, Myths,

&c., of Ireland, 78 seq. Parallels. — The

latter half resembles the second part of the Sea-Maiden

(No. xvii.), which see. The earlier portion is a Cinderella tale (on

which see the

late Mr. Ralston's article in Nineteenth Century, Nov. 1879,

and Mr. Lang's

treatment in his Perrault). Miss Roalfe Cox is about to publish for the

Folk-Lore

Society a whole volume of variants of the Cinderella group of stories,

which are

remarkably well represented in these isles, nearly a dozen different

versions being

known in England, Ireland, and Scotland. XX. JACK AND

HIS MASTER. Source. — Kennedy,

Fireside Stories of Ireland, 74-80, "Shan

an Omadhan and his Master." Parallels. — It

occurs also in Campbell, No. xlv., "Mac a Rusgaich."

It is a European droll, the wide occurrence of which — "the loss of

temper

bet" I should call it — is bibliographised by M. Cosquin, l.c.

ii. 50

(cf. notes on No. vi.). XXI. BETH

GELLERT. Source. — I have

paraphrased the well-known poem of Hon. W. R. Spencer,

"Beth Gêlert, or the Grave of the Greyhound," first printed privately

as a broadsheet in 1800 when it was composed ("August 11, 1800,

Dolymalynllyn"

is the colophon). It was published in Spencer's Poems, 1811,

pp. 78-86. These

dates, it will be seen, are of importance. Spencer states in a note:

"The story

of this ballad is traditionary in a village at the foot of Snowdon

where Llewellyn

the Great had a house. The Greyhound named Gêlert was given him by his

father-in-law,

King John, in the year 1205, and the place to this day is called

Beth-Gêlert, or

the grave of Gêlert." As a matter of fact, no trace of the tradition in

connection

with Bedd Gellert can be found before Spencer's time. It is not

mentioned in Leland's

Itinerary, ed. Hearne, v. p. 37 ("Beth Kellarth"), in

Pennant's

Tour (1770), ii. 176, or in Bingley's Tour in Wales

(1800). Borrow

in his Wild Wales, p. 146, gives the legend, but does not

profess to derive

it from local tradition. Parallels. — The only

parallel in Celtdom is that noticed by Croker in

his third volume, the legend of Partholan who killed his wife's

greyhound from jealousy:

this is found sculptured in stone at Ap Brune, co. Limerick. As is well

known, and

has been elaborately discussed by Mr. Baring-Gould (Curious Myths of

the Middle

Ages, p. 134 seq.), and Mr. W. A. Clouston (Popular

Tales and Fictions,

ii. 166, seq.), the story of the man who rashly slew the dog

(ichneumon,

weasel, &c.) that had saved his babe from death, is one of those

which have

spread from East to West. It is indeed, as Mr. Clouston points out,

still current

in India, the land of its birth. There is little doubt that it is

originally Buddhistic:

the late Prof. S. Beal gave the earliest known version from the Chinese

translation

of the Vinaya Pitaka in the Academy of Nov. 4, 1882.

The conception

of an animal sacrificing itself for the sake of others is peculiarly

Buddhistic;

the "hare in the moon" is an apotheosis of such a piece of

self-sacrifice

on the part of Buddha (Sasa Jataka). There are two forms that

have reached

the West, the first being that of an animal saving men at the cost of

its own life.

I pointed out an early instance of this, quoted by a Rabbi of the

second century,

in my Fables of Aesop, i. 105. This concludes with a strangely

close parallel

to Gellert; "They raised a cairn over his grave, and the place is still

called

The Dog's Grave." The Culex attributed to Virgil seems to be

another

variant of this. The second form of the legend is always told as a

moral apologue

against precipitate action, and originally occurred in The Fables

of Bidpai

in its hundred and one forms, all founded on Buddhistic originals (cf.

Benfey,

Pantschatantra, Einleitung, §201). [Footnote: It occurs in

the same chapter

as the story of La Perrette, which has been traced, after Benfey, by

Prof. M. Müller

in his "Migration of Fables" (Sel. Essays, i. 500-74): exactly

the same history applies to Gellert.] Thence, according to Benfey, it

was inserted

in the Book of Sindibad, another collection of Oriental

Apologues framed

on what may be called the Mrs. Potiphar formula. This came to Europe

with the Crusades,

and is known in its Western versions as the Seven Sages of Rome.

The Gellert

story occurs in all the Oriental and Occidental versions; e.g.,

it is the

First Master's story in Wynkyn de Worde's (ed. G. L. Gomme, for the

Villon Society.)

From the Seven Sages it was taken into the particular branch of

the Gesta

Romanorum current in England and known as the English Gesta,

where it

occurs as c. xxxii., "Story of Folliculus." We have thus traced it to

England whence it passed to Wales, where I have discovered it as the

second apologue

of "The Fables of Cattwg the Wise," in the Iolo MS. published by the

Welsh

MS. Society, p.561, "The man who killed his Greyhound." (These Fables,

Mr. Nutt informs me, are a pseudonymous production probably of the

sixteenth century.)

This concludes the literary route of the Legend of Gellert from India

to Wales:

Buddhistic Vinaya Pitaka — Fables of Bidpai; — Oriental Sindibad;

— Occidental Seven Sages of Rome; — "English" (Latin), Gesta

Romanorum; — Welsh, Fables of Cattwg. Remarks. — We have

still to connect the legend with Llewelyn and with

Bedd Gelert. But first it may be desirable to point out why it is

necessary to assume

that the legend is a legend and not a fact. The saving of an infant's

life by a

dog, and the mistaken slaughter of the dog, are not such an improbable

combination

as to make it impossible that the same event occurred in many places.

But what is

impossible, in my opinion, is that such an event should have

independently been

used in different places as the typical instance of, and warning

against, rash action.

That the Gellert legend, before it was localised, was used as a moral

apologue in

Wales is shown by the fact that it occurs among the Fables of Cattwg,

which are

all of that character. It was also utilised as a proverb: "Yr wy'n

edivaru

cymmaint a'r Gwr a laddodd ei Vilgi" ("I repent as much as the man

who slew his greyhound"). The fable indeed, from this point of view,

seems

greatly to have attracted the Welsh mind, perhaps as of especial value

to a proverbially

impetuous temperament. Croker (Fairy Legends of Ireland, vol.

iii. p. 165)

points out several places where the legend seems to have been localised

in place-names

— two places, called "Gwal y Vilast" ("Greyhound's Couch"),

in Carmarthen and Glamorganshire; "Llech y Asp" ("Dog's Stone"),

in Cardigan, and another place named in Welsh "Spring of the

Greyhound's Stone."

Mr. Baring-Gould mentions that the legend is told of an ordinary

tombstone, with

a knight and a greyhound, in Abergavenny Church; while the Fable of

Cattwg is told

of a man in Abergarwan. So widespread and well known was the legend

that it was

in Richard III's time adopted as the national crest. In the Warwick

Roll, at the

Herald's Office, after giving separate crests for England, Scotland,

and Ireland,

that for Wales is given as figured in the margin, and blazoned "on a

coronet

in a cradle or, a greyhound argent for Walys" (see J. R. Planché, Twelve

Designs for the Costume of Shakespeare's Richard III., 1830,

frontispiece).

If this Roll is authentic, the popularity of the legend is thrown back

into the

fifteenth century. It still remains to explain how and when this

general legend

of rash action was localised and specialised at Bedd Gelert: I believe

I have discovered

this. There certainly was a local legend about a dog named Gelert at

that place;

E. Jones, in the first edition of his Musical Relicks of the Welsh

Bards,

1784, p. 40, gives the following englyn or epigram: Claddwyd Cylart celfydd

(ymlyniad) Ymlaneau Efionydd Parod giuio i'w gynydd Parai'r dydd yr heliai

Hydd; which he

Englishes thus: The remains of famed

Cylart, so faithful and good, The bounds of the cantred

conceal; Whenever the doe or the

stag he pursued His master was sure

of a meal. No reference

was made in the first edition to the Gellert legend, but in the second

edition of

1794, p. 75, a note was added telling the legend, "There is a general

tradition

in North Wales that a wolf had entered the house of Prince Llewellyn.

Soon after

the Prince returned home, and, going into the nursery, he met his dog Kill-hart,

all bloody and wagging his tail at him; Prince Llewellyn, on entering

the room found

the cradle where his child lay overturned, and the floor flowing with

blood; imagining

that the greyhound had killed the child, he immediately drew his sword

and stabbed

it; then, turning up the cradle, found under it the child alive, and

the wolf dead.

This so grieved the Prince, that he erected a tomb over his faithful

dog's grave;

where afterwards the parish church was built and goes by that name — Bedd

Cilhart,

or the grave of Kill-hart, in Carnarvonshire. From this

incident is elicited

a very common Welsh proverb [that given above which occurs also in 'The

Fables of

Cattwg;' it will be observed that it is quite indefinite.]" "Prince

Llewellyn

ab Jorwerth married Joan, [natural] daughter of King John, by Agatha,

daughter

of Robert Ferrers, Earl of Derby; and the dog was a present to the

prince from his

father-in-law about the year 1205." It was clearly from this note that

the

Hon. Mr. Spencer got his account; oral tradition does not indulge in

dates Anno

Domini. The application of the general legend of "the man who slew

his

greyhound" to the dog Cylart, was due to the learning of E. Jones,

author of

the Musical Relicks. I am convinced of this, for by a lucky

chance I am enabled

to give the real legend about Cylart, which is thus given in Carlisle's

Topographical

Dictionary of Wales, s.v., "Bedd Celert," published in 1811, the

date

of publication of Mr. Spencer's Poems. "Its name, according to

tradition,

implies The Grave of Celert, a Greyhound which belonged to

Llywelyn, the

last Prince of Wales: and a large Rock is still pointed out as the

monument of this

celebrated Dog, being on the spot where it was found dead, together

with the stag

which it had pursued from Carnarvon," which is thirteen miles distant.

The

cairn was thus a monument of a "record" run of a greyhound: the englyn

quoted by Jones is suitable enough for this, while quite inadequate to

record the

later legendary exploits of Gêlert. Jones found an englyn

devoted to an

exploit of a dog named Cylart, and chose to interpret it in his second

edition,

1794, as the exploit of a greyhound with which all the world

(in Wales) were

acquainted. Mr. Spencer took the legend from Jones (the reference to

the date 1205

proves that), enshrined it in his somewhat banal verses, which

were lucky

enough to be copied into several reading-books, and thus became known

to all English-speaking

folk. It remains

only to explain why Jones connected the legend with Llewelyn. Llewelyn

had local

connection with Bedd Gellert, which was the seat of an Augustinian

abbey, one of

the oldest in Wales. An inspeximus of Edward I. given in Dugdale, Monast.

Angl.,

ed. pr. ii. 100a, quotes as the earliest charter of the abbey "Cartam

Lewelin,

magni." The name of the abbey was "Beth Kellarth"; the name is thus

given by Leland, l.c., and as late as 1794 an engraving at the

British Museum

is entitled "Beth Kelert," while Carlisle gives it as "Beth Celert."

The place was thus named after the abbey, not after the cairn or rock.

This is confirmed

by the fact of which Prof. Rhys had informed me, that the collocation

of letters

rt is un-Welsh. Under these circumstances it is not

impossible, I think,

that the earlier legend of the marvellous run of "Cylart" from

Carnarvon

was due to the etymologising fancy of some English-speaking Welshman

who interpreted

the name as Killhart, so that the simpler legend would be only a

folk-etymology. But whether

Kellarth, Kelert, Cylart, Gêlert or Gellert ever existed and ran a hart

from Carnarvon

to Bedd Gellert or no, there can be little doubt after the preceding

that he was

not the original hero of the fable of "the man that slew his

greyhound,"

which came to Wales from Buddhistic India through channels which are

perfectly traceable.

It was Edward Jones who first raised him to that proud position, and

William Spencer

who securely installed him there, probably for all time. The legend is

now firmly

established at Bedd Gellert. There is said to be an ancient air, "Bedd

Gelert,"

"as sung by the Ancient Britons"; it is given in a pamphlet published

at Carnarvon in the "fifties," entitled Gellert's Grave; or,

Llewellyn's

Rashness: a Ballad, by the Hon. W. R. Spencer, to which is added that

ancient Welsh

air, "Bedd Gelert," as sung by the Ancient Britons. The air is from

R. Roberts' "Collection of Welsh Airs," but what connection it has with

the legend I have been unable to ascertain. This is probably another

case of adapting

one tradition to another. It is almost impossible to distinguish

palaeozoic and

cainozoic strata in oral tradition. According to Murray's Guide to

N. Wales,

p. 125, the only authority for the cairn now shown is that of the

landlord of the

Goat Inn, "who felt compelled by the cravings of tourists to invent a

grave."

Some old men at Bedd Gellert, Prof. Rhys informs me, are ready to

testify that they

saw the cairn laid. They might almost have been present at the birth of

the legend,

which, if my affiliation of it is correct, is not yet quite 100 years

old. XXII. STORY

OF IVAN. Source. — Lluyd, Archaeologia

Britannia, 1707, the first comparative

Celtic grammar and the finest piece of work in comparative philology

hitherto done

in England, contains this tale as a specimen of Cornish then still

spoken in Cornwall.

I have used the English version contained in Blackwood's Magazine

as long

ago as May 1818. I have taken the third counsel from the Irish version,

as the original

is not suited virginibus puerisque, though harmless enough in

itself. Parallels. — Lover

has a tale, The Three Advices. It occurs also

in modern Cornwall ap. Hunt, Drolls of West of England,

344, "The

Tinner of Chyamor." Borrow, Wild Wales, 41, has a reference

which seems

to imply that the story had crystallised into a Welsh proverb.

Curiously enough,

it forms the chief episode of the so-called "Irish Odyssey" ("Merugud

Uilix maiec Leirtis" — "Wandering of Ulysses M'Laertes"). It

was derived, in all probability, from the Gesta Romanorum, c.

103, where

two of the three pieces of advice are "Avoid a byeway," "Beware of

a house where the housewife is younger than her husband." It is likely

enough

that this chapter, like others of the Gesta, came from the

East, for it is

found in some versions of "The Forty Viziers," and in the Turkish

Tales

(see Oesterley's parallels and Gesta, ed. Swan and Hooper, note

9). XXIII.

ANDREW COFFEY. Source. — From the

late D. W. Logie, written down by Mr. Alfred Nutt. Parallels. — Dr.

Hyde's "Teig O'Kane and the Corpse," and Kennedy's

"Cauth Morrisy," Legend. Fict., 158, are practically the same. Remarks. — No

collection of Celtic Folk-Tales would be representative

that did not contain some specimen of the gruesome. The most effective

ghoul story

in existence is Lover's "Brown Man." XXIV. BATTLE

OF BIRDS. Source. — Campbell

(Pop. Tales, W. Highlands, No. ii.), with

touches from the seventh variant and others, including the casket and

key finish,

from Curtin's "Son of the King of Erin" (Myths, &c., 32 seq.).

I have also added a specimen of the humorous end pieces added by Gaelic

story-tellers;

on these tags see an interesting note in MacDougall's Tales,

note on p. 112.

I have found some difficulty in dealing with Campbell's excessive use

of the second

person singular, "If thou thouest him some two or three times, 'tis

well,"

but beyond that it is wearisome. Practically, I have reserved thou

for the

speech of giants, who may be supposed to be somewhat old-fashioned. I

fear, however,

I have not been quite consistent, though the you's addressed to

the apple-pips

are grammatically correct as applied to the pair of lovers. Parallels. — Besides

the eight versions given or abstracted by Campbell

and Mr. Curtin's, there is Carleton's "Three Tasks," Dr. Hyde's "Son

of Branduf" (MS.); there is the First Tale of MacInnes (where see Mr.

Nutt's

elaborate notes, 431-43), two in the Celtic Magazine, vol.

xii., "Grey

Norris from Warland" (Folk-Lore Journ. i. 316), and Mr. Lang's

Morayshire

Tale, "Nicht Nought Nothing" (see Eng. Fairy Tales, No. vii.),

no less than sixteen variants found among the Celts. It must have

occurred early

among them. Mr. Nutt found the feather-thatch incident in the Agallamh

na Senoraib

("Discourse of Elders"), which is at least as old as the fifteenth

century.