| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

The Battle

of the Birds

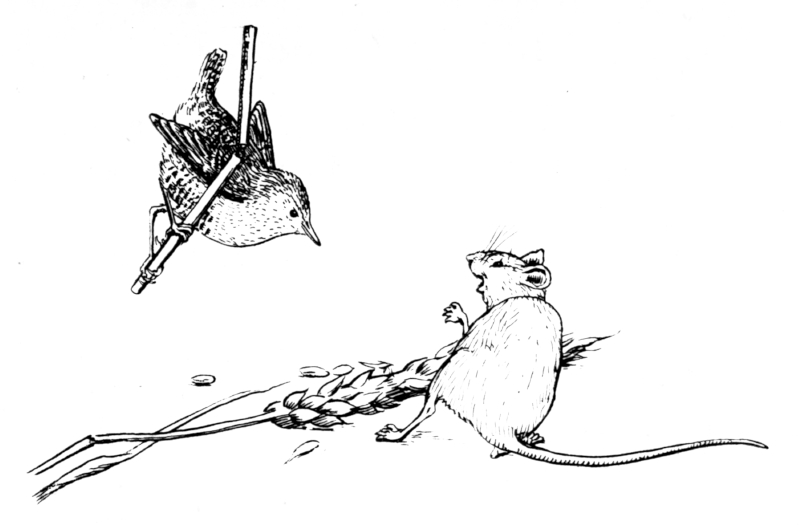

"I

am seeking a servant," said the farmer to the wren. "Will

you take me?" said the wren. "You,

you poor creature, what good would you do?" "Try

me," said the wren. So he

engaged him, and the first work he set him to do was threshing in the

barn. The

wren threshed (what did he thresh with? Why a flail to be sure), and he

knocked

off one grain. A mouse came out and she eats that. "I'll

trouble you not to do that again," said the wren. He struck

again, and he struck off two grains. Out came the mouse and she eats

them. So they

arranged a contest to see who was strongest, and the wren brings his

twelve birds,

and the mouse her tribe. "You

have your tribe with you," said the wren. "As

well as yourself," said the mouse, and she struck out her leg proudly.

But

the wren broke it with his flail, and there was a pitched battle on a

set day. When every

creature and bird was gathering to battle, the son of the king of

Tethertown said

that he would go to see the battle, and that he would bring sure word

home to his

father the king, who would be king of the creatures this year. The

battle was over

before he arrived all but one fight, between a great black raven and a

snake. The

snake was twined about the raven's neck, and the raven held the snake's

throat in

his beak, and it seemed as if the snake would get the victory over the

raven. When

the king's son saw this he helped the raven, and with one blow takes

the head off

the snake. When the raven had taken breath, and saw that the snake was

dead, he

said, "For thy kindness to me this day, I will give thee a sight. Come

up now

on the root of my two wings." The king's son put his hands about the

raven

before his wings, and, before he stopped, he took him over nine Bens,

and nine Glens,

and nine Mountain Moors. "Now,"

said the raven, "see you that house yonder? Go now to it. It is a

sister of

mine that makes her dwelling in it; and I will go bail that you are

welcome. And

if she asks you, Were you at the battle of the birds? say you were. And

if she asks,

'Did you see any one like me,' say you did, but be sure that you meet

me to-morrow

morning here, in this place." The king's son got good and right good

treatment

that night. Meat of each meat, drink of each drink, warm water to his

feet, and

a soft bed for his limbs. On the

next day the raven gave him the same sight over six Bens, and six

Glens, and six

Mountain Moors. They saw a bothy far off, but, though far off, they

were soon there.

He got good treatment this night, as before — plenty of meat and drink,

and warm

water to his feet, and a soft bed to his limbs — and on the next day it

was the

same thing, over three Bens and three Glens, and three Mountain Moors. On the

third morning, instead of seeing the raven as at the other times, who

should meet

him but the handsomest lad he ever saw, with gold rings in his hair,

with a bundle

in his hand. The king's son asked this lad if he had seen a big black

raven. Said the

lad to him, "You will never see the raven again, for I am that raven. I

was

put under spells by a bad druid; it was meeting you that loosed me, and

for that

you shall get this bundle. Now," said the lad, "you must turn back on

the self-same steps, and lie a night in each house as before; but you

must not loose

the bundle which I gave ye, till in the place where you would most wish

to dwell." The king's

son turned his back to the lad, and his face to his father's house; and

he got lodging

from the raven's sisters, just as he got it when going forward. When he

was nearing

his father's house he was going through a close wood. It seemed to him

that the

bundle was growing heavy, and he thought he would look what was in it. When he

loosed the bundle he was astonished. In a twinkling he sees the very

grandest place

he ever saw. A great castle, and an orchard about the castle, in which

was every

kind of fruit and herb. He stood full of wonder and regret for having

loosed the

bundle — for it was not in his power to put it back again — and he

would have wished

this pretty place to be in the pretty little green hollow that was

opposite his

father's house; but he looked up and saw a great giant coming towards

him. "Bad's

the place where you have built the house, king's son," says the giant. "Yes,

but it is not here I would wish it to be, though it happens to be here

by mishap,"

says the king's son. "What's

the reward for putting it back in the bundle as it was before?" "What's

the reward you would ask?" says the king's son. "That

you will give me the first son you have when he is seven years of age,"

says

the giant. "If

I have a son you shall have him," said the king's son. In a

twinkling

the giant put each garden, and orchard, and castle in the bundle as

they were before. "Now,"

says the giant, "take your own road, and I will take mine; but mind

your promise,

and if you forget I will remember." The king's

son took to the road, and at the end of a few days he reached the place

he was fondest

of. He loosed the bundle, and the castle was just as it was before. And

when he

opened the castle door he sees the handsomest maiden he ever cast eye

upon. "Advance,

king's son," said the pretty maid; "everything is in order for you, if

you will marry me this very day." "It's

I that am willing," said the king's son. And on the same day they

married. But at

the end of a day and seven years, who should be seen coming to the

castle but the

giant. The king's son was reminded of his promise to the giant, and

till now he

had not told his promise to the queen. "Leave

the matter between me and the giant," says the queen. "Turn

out your son," says the giant; "mind your promise." "You

shall have him," says the king, "when his mother puts him in order for

his journey." The queen

dressed up the cook's son, and she gave him to the giant by the hand.

The giant

went away with him; but he had not gone far when he put a rod in the

hand of the

little laddie. The giant asked him — "If

thy father had that rod what would he do with it?" "If

my father had that rod he would beat the dogs and the cats, so that

they shouldn't

be going near the king's meat," said the little laddie. "Thou'rt

the cook's son," said the giant. He catches him by the two small ankles

and

knocks him against the stone that was beside him. The giant turned back

to the castle

in rage and madness, and he said that if they did not send out the

king's son to

him, the highest stone of the castle would be the lowest. Said the

queen to the king, "We'll try it yet; the butler's son is of the same

age as

our son." She dressed

up the butler's son, and she gives him to the giant by the hand. The

giant had not

gone far when he put the rod in his hand. "If

thy father had that rod," says the giant, "what would he do with it?" "He

would beat the dogs and the cats when they would be coming near the

king's bottles

and glasses." "Thou

art the son of the butler," says the giant and dashed his brains out

too. The

giant returned in a very great rage and anger. The earth shook under

the sole of

his feet, and the castle shook and all that was in it. "OUT

HERE WITH THY SON," says the giant, "or in a twinkling the stone that

is highest in the dwelling will be the lowest." So they had to give the

king's

son to the giant. When they

were gone a little bit from the earth, the giant showed him the rod

that was in

his hand and said: "What would thy father do with this rod if he had

it?" The king's

son said: "My father has a braver rod than that." And the

giant asked him, "Where is thy father when he has that brave rod?" And the

king's son said: "He will be sitting in his kingly chair." Then the

giant understood that he had the right one. The giant

took him to his own house, and he reared him as his own son. On a day

of days when

the giant was from home, the lad heard the sweetest music he ever heard

in a room

at the top of the giant's house. At a glance he saw the finest face he

had ever

seen. She beckoned to him to come a bit nearer to her, and she said her

name was

Auburn Mary but she told him to go this time, but to be sure to be at

the same place

about that dead midnight. And as

he promised he did. The giant's daughter was at his side in a

twinkling, and she

said, "To-morrow you will get the choice of my two sisters to marry;

but say

that you will not take either, but me. My father wants me to marry the

son of the

king of the Green City, but I don't like him." On the morrow the giant

took

out his three daughters, and he said: "Now,

son of the king of Tethertown, thou hast not lost by living with me so

long. Thou

wilt get to wife one of the two eldest of my daughters, and with her

leave to go

home with her the day after the wedding." "If

you will give me this pretty little one," says the king's son, "I will

take you at your word." The giant's

wrath kindled, and he said: "Before thou gett'st her thou must do the

three

things that I ask thee to do." "Say

on," says the king's son. The giant

took him to the byre. "Now,"

says the giant, "a hundred cattle are stabled here, and it has not been

cleansed

for seven years. I am going from home to-day, and if this byre is not

cleaned before

night comes, so clean that a golden apple will run from end to end of

it, not only

thou shalt not get my daughter, but 'tis only a drink of thy fresh,

goodly, beautiful

blood that will quench my thirst this night." He begins

cleaning the byre, but he might just as well to keep baling the great

ocean. After

midday when sweat was blinding him, the giant's youngest daughter came

where he

was, and she said to him: "You

are being punished, king's son." "I

am that," says the king's son. "Come

over," says Auburn Mary, "and lay down your weariness." "I

will do that," says he, "there is but death awaiting me, at any rate."

He sat down near her. He was so tired that he fell asleep beside her.

When he awoke,

the giant's daughter was not to be seen, but the byre was so well

cleaned that a

golden apple would run from end to end of it and raise no stain. In

comes the giant,

and he said: "Hast

thou cleaned the byre, king's son?" "I

have cleaned it," says he. "Somebody

cleaned it," says the giant. "You

did not clean it, at all events," said the king's son. "Well,

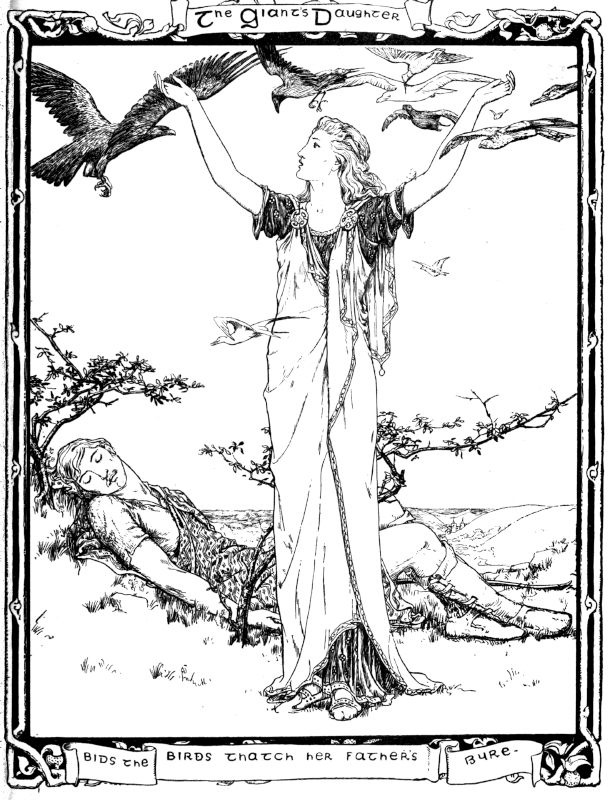

well!" says the giant, "since thou wert so active to-day, thou wilt get

to this time to-morrow to thatch this byre with birds' down, from birds

with no

two feathers of one colour." The king's

son was on foot before the sun; he caught up his bow and his quiver of

arrows to

kill the birds. He took to the moors, but if he did, the birds were not

so easy

to take. He was running after them till the sweat was blinding him.

About mid-day

who should come but Auburn Mary. "You

are exhausting yourself, king's son," says she. "I

am," said he. "There

fell but these two blackbirds, and both of one colour." "Come

over and lay down your weariness on this pretty hillock," says the

giant's

daughter. "It's

I am willing," said he. He thought

she would aid him this time, too, and he sat down near her, and he was

not long

there till he fell asleep. When he

awoke, Auburn Mary was gone. He thought he would go back to the house,

and he sees

the byre thatched with feathers. When the giant came home, he said: "Hast

thou thatched the byre, king's son?" "I

thatched it," says he. "Somebody

thatched it," says the giant. "You

did not thatch it," says the king's son. "Yes,

yes!" says the giant. "Now," says the giant, "there is a fir

tree beside that loch down there, and there is a magpie's nest in its

top. The eggs

thou wilt find in the nest. I must have them for my first meal. Not one

must be

burst or broken, and there are five in the nest." Early

in the morning the king's son went where the tree was, and that tree

was not hard

to hit upon. Its match was not in the whole wood. From the foot to the

first branch

was five hundred feet. The king's son was going all round the tree. She

came who

was always bringing help to him. "You

are losing the skin of your hands and feet." "Ach!

I am," says he. "I am no sooner up than down." "This

is no time for stopping," says the giant's daughter. "Now you must kill

me, strip the flesh from my bones, take all those bones apart, and use

them as steps

for climbing the tree. When you are climbing the tree, they will stick

to the glass

as if they had grown out of it; but when you are coming down, and have

put your

foot on each one, they will drop into your hand when you touch them. Be

sure and

stand on each bone, leave none untouched; if you do, it will stay

behind. Put all

my flesh into this clean cloth by the side of the spring at the roots

of the tree.

When you come to the earth, arrange my bones together, put the flesh

over them,

sprinkle it with water from the spring, and I shall be alive before

you. But don't

forget a bone of me on the tree."  "How

could I kill you," asked the king's son, "after what you have done for

me?" "If

you won't obey, you and I are done for," said Auburn Mary. "You must

climb

the tree, or we are lost; and to climb the tree you must do as I say."

The

king's son obeyed. He killed Auburn Mary, cut the flesh from her body,

and unjointed

the bones, as she had told him. As he

went up, the king's son put the bones of Auburn Mary's body against the

side of

the tree, using them as steps, till he came under the nest and stood on

the last

bone. Then he

took the eggs, and coming down, put his foot on every bone, then took

it with him,

till he came to the last bone, which was so near the ground that he

failed to touch

it with his foot. He now

placed all the bones of Auburn Mary in order again at the side of the

spring, put

the flesh on them, sprinkled it with water from the spring. She rose up

before him,

and said: "Didn't I tell you not to leave a bone of my body without

stepping

on it? Now I am lame for life! You left my little finger on the tree

without touching

it, and I have but nine fingers." "Now,"

says she, "go home with the eggs quickly, and you will get me to marry

to-night

if you can know me. I and my two sisters will be arrayed in the same

garments, and

made like each other, but look at me when my father says, 'Go to thy

wife, king's

son;' and you will see a hand without a little finger." He gave

the eggs to the giant. "Yes,

yes!" says the giant, "be making ready for your marriage." Then,

indeed, there was a wedding, and it was a wedding! Giants and

gentlemen,

and the son of the king of the Green City was in the midst of them.

They were married,

and the dancing began, that was a dance! The giant's house was shaking

from top

to bottom. But bed

time came, and the giant said, "It is time for thee to go to rest, son

of the

king of Tethertown; choose thy bride to take with thee from amidst

those." She put

out the hand off which the little finger was, and he caught her by the

hand. "Thou

hast aimed well this time too; but there is no knowing but we may meet

thee another

way," said the giant. But to

rest they went. "Now," says she, "sleep not, or else you are a dead

man. We must fly quick, quick, or for certain my father will kill you." Out they

went, and on the blue grey filly in the stable they mounted. "Stop a

while,"

says she, "and I will play a trick to the old hero." She jumped in, and

cut an apple into nine shares, and she put two shares at the head of

the bed, and

two shares at the foot of the bed, and two shares at the door of the

kitchen, and

two shares at the big door, and one outside the house. The giant

awoke and called, "Are you asleep?" "Not

yet," said the apple that was at the head of the bed. At the

end of a while he called again. "Not

yet," said the apple that was at the foot of the bed. A while

after this he called again: "Are your asleep?" "Not

yet," said the apple at the kitchen door. The giant

called again. The apple

that was at the big door answered. "You

are now going far from me," says the giant. "Not

yet," says the apple that was outside the house. "You

are flying," says the giant. The giant jumped on his feet, and to the

bed he

went, but it was cold — empty. "My

own daughter's tricks are trying me," said the giant. "Here's after

them,"

says he. At the

mouth of day, the giant's daughter said that her father's breath was

burning her

back. "Put

your hand, quick," said she, "in the ear of the grey filly, and

whatever

you find in it, throw it behind us." "There

is a twig of sloe tree," said he. "Throw

it behind us," said she. No sooner

did he that, than there were twenty miles of blackthorn wood, so thick

that scarce

a weasel could go through it. The giant

came headlong, and there he is fleecing his head and neck in the thorns. "My

own daughter's tricks are here as before," said the giant; "but if I

had

my own big axe and wood knife here, I would not be long making a way

through this." He went

home for the big axe and the wood knife, and sure he was not long on

his journey,

and he was the boy behind the big axe. He was not long making a way

through the

blackthorn. "I

will leave the axe and the wood knife here till I return," says he. "If

you leave 'em, leave 'em," said a hoodie that was in a tree, "we'll

steal

'em, steal 'em." "If

you will do that," says the giant, "I must take them home." He returned

home and left them at the house. At the

heat of day the giant's daughter felt her father's breath burning her

back. "Put

your finger in the filly's ear, and throw behind whatever you find in

it." He got

a splinter of grey stone, and in a twinkling there were twenty miles,

by breadth

and height, of great grey rock behind them. The giant

came full pelt, but past the rock he could not go. "The

tricks of my own daughter are the hardest things that ever met me,"

says the

giant; "but if I had my lever and my mighty mattock, I would not be

long in

making my way through this rock also." There

was no help for it, but to turn the chase for them; and he was the boy

to split

the stones. He was not long in making a road through the rock. "I

will leave the tools here, and I will return no more." "If

you leave 'em, leave 'em," says the hoodie, "we will steal 'em, steal

'em." "Do

that if you will; there is no time to go back." At the

time of breaking the watch, the giant's daughter said that she felt her

father's

breath burning her back. "Look

in the filly's ear, king's son, or else we are lost." He did

so, and it was a bladder of water that was in her ear this time. He

threw it behind

him and there was a fresh-water loch, twenty miles in length and

breadth, behind

them. The giant

came on, but with the speed he had on him, he was in the middle of the

loch, and

he went under, and he rose no more. On the

next day the young companions were come in sight of his father's house.

"Now,"

says she, "my father is drowned, and he won't trouble us any more; but

before

we go further," says she, "go you to your father's house, and tell that

you have the likes of me; but let neither man nor creature kiss you,

for if you

do, you will not remember that you have ever seen me." Every

one he met gave him welcome and luck, and he charged his father and

mother not to

kiss him; but as mishap was to be, an old greyhound was indoors, and

she knew him,

and jumped up to his mouth, and after that he did not remember the

giant's daughter. She was

sitting at the well's side as he left her, but the king's son was not

coming. In

the mouth of night she climbed up into a tree of oak that was beside

the well, and

she lay in the fork of that tree all night. A shoemaker had a house

near the well,

and about mid-day on the morrow, the shoemaker asked his wife to go for

a drink

for him out of the well. When the shoemaker's wife reached the well,

and when she

saw the shadow of her that was in the tree, thinking it was her own

shadow — and

she never thought till now that she was so handsome — she gave a cast

to the dish

that was in her hand, and it was broken on the ground, and she took

herself to the

house without vessel or water. "Where

is the water, wife?" said the shoemaker. "You

shambling, contemptible old carle, without grace, I have stayed too

long your water

and wood thrall." "I

think, wife, that you have turned crazy. Go you, daughter, quickly, and

fetch a

drink for your father." His daughter

went, and in the same way so it happened to her. She never thought till

now that

she was so lovable, and she took herself home. "Up

with the drink," said her father. "You

home-spun shoe carle, do you think I am fit to be your thrall?" The poor

shoemaker thought that they had taken a turn in their understandings,

and he went

himself to the well. He saw the shadow of the maiden in the well, and

he looked

up to the tree, and he sees the finest woman he ever saw. "Your

seat is wavering, but your face is fair," said the shoemaker. The

shoemaker

understood that this was the shadow that had driven his people mad. The

shoemaker

took her to his house, and he said that he had but a poor bothy, but

that she should

get a share of all that was in it. One day,

the shoemaker had shoes ready, for on that very day the king's son was

to be married.

The shoemaker was going to the castle with the shoes of the young

people, and the

girl said to the shoemaker, "I would like to get a sight of the king's

son

before he marries." "Come

with me," says the shoemaker, "I am well acquainted with the servants

at the castle, and you shall get a sight of the king's son and all the

company." And when

the gentles saw the pretty woman that was here they took her to the

wedding-room,

and they filled for her a glass of wine. When she was going to drink

what is in

it, a flame went up out of the glass, and a golden pigeon and a silver

pigeon sprang

out of it. They were flying about when three grains of barley fell on

the floor.

The silver pigeon sprung, and ate that up. Said the

golden pigeon to him, "If you remembered when I cleared the byre, you

would

not eat that without giving me a share." Again

there fell three other grains of barley, and the silver pigeon sprung,

and ate that

up as before. "If

you remembered when I thatched the byre, you would not eat that without

giving me

my share," says the golden pigeon. Three

other grains fall, and the silver pigeon sprung, and ate that up. "If

you remembered when I harried the magpie's nest, you would not eat that

without

giving me my share," says the golden pigeon; "I lost my little finger

bringing it down, and I want it still." The king's

son minded, and he knew who it was that was before him. "Well,"

said the king's son to the guests at the feast, "when I was a little

younger

than I am now, I lost the key of a casket that I had. I had a new key

made, but

after it was brought to me I found the old one. Now, I'll leave it to

any one here

to tell me what I am to do. Which of the keys should I keep?" "My

advice to you," said one of the guests, "is to keep the old key, for it

fits the lock better and you're more used to it." Then the

king's son stood up and said: "I thank you for a wise advice and an

honest

word. This is my bride the daughter of the giant who saved my life at

the risk of

her own. I'll have her and no other woman." So the

king's son married Auburn Mary and the wedding lasted long and all were

happy. But

all I got was butter on a live coal, porridge in a basket, and they

sent me for

water to the stream, and the paper shoes came to an end. |