| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| The

Story-Teller at Fault

One morning

the story-teller arose early, and as his custom was, strolled out into

his garden

turning over in his mind incidents which he might weave into a story

for the king

at night. But this morning he found himself quite at fault; after

pacing his whole

demesne, he returned to his house without being able to think of

anything new or

strange. He found no difficulty in "there was once a king who had three

sons"

or "one day the king of all Ireland," but further than that he could

not

get. At length he went in to breakfast, and found his wife much

perplexed at his

delay. "Why

don't you come to breakfast, my dear?" said she. "I

have no mind to eat anything," replied the story-teller; "long as I

have

been in the service of the king of Leinster, I never sat down to

breakfast without

having a new story ready for the evening, but this morning my mind is

quite shut

up, and I don't know what to do. I might as well lie down and die at

once. I'll

be disgraced for ever this evening, when the king calls for his

story-teller." Just at

this moment the lady looked out of the window. "Do

you see that black thing at the end of the field?" said she. "I

do," replied her husband. They drew

nigh, and saw a miserable looking old man lying on the ground with a

wooden leg

placed beside him. "Who

are you, my good man?" asked the story-teller. "Oh,

then, 'tis little matter who I am. I'm a poor, old, lame, decrepit,

miserable creature,

sitting down here to rest awhile." "An'

what are you doing with that box and dice I see in your hand?" "I

am waiting here to see if any one will play a game with me," replied

the beggar

man. "Play

with you! Why what has a poor old man like you to play for?" "I

have one hundred pieces of gold in this leathern purse," replied the

old man. "You

may as well play with him," said the story-teller's wife; "and perhaps

you'll have something to tell the king in the evening." A smooth

stone was placed between them, and upon it they cast their throws. It was

but a little while and the story-teller lost every penny of his money. "Much

good may it do you, friend," said he. "What better hap could I look

for,

fool that I am!" "Will

you play again?" asked the old man. "Don't

be talking, man: you have all my money." "Haven't

you chariot and horses and hounds?" "Well,

what of them!" "I'll

stake all the money I have against thine." "Nonsense,

man! Do you think for all the money in Ireland, I'd run the risk of

seeing my lady

tramp home on foot?" "Maybe

you'd win," said the bocough. "Maybe

I wouldn't," said the story-teller. "Play

with him, husband," said his wife. "I don't mind walking, if you do,

love." "I

never refused you before," said the story-teller, "and I won't do so

now." Down he

sat again, and in one throw lost houses, hounds, and chariot. "Will

you play again?" asked the beggar. "Are

you making game of me, man; what else have I to stake?" "I'll

stake all my winnings against your wife," said the old man. The

story-teller

turned away in silence, but his wife stopped him. "Accept

his offer," said she. "This is the third time, and who knows what luck

you may have? You'll surely win now." They played

again, and the story-teller lost. No sooner had he done so, than to his

sorrow and

surprise, his wife went and sat down near the ugly old beggar. "Is

that the way you're leaving me?" said the story-teller. "Sure

I was won," said she. "You would not cheat the poor man, would you?" "Have

you any more to stake?" asked the old man. "You

know very well I have not," replied the story-teller. "I'll

stake the whole now, wife and all, against your own self," said the old

man. Again

they played, and again the story-teller lost. "Well!

here I am, and what do you want with me?" "I'll

soon let you know," said the old man, and he took from his pocket a

long cord

and a wand. "Now,"

said he to the story-teller, "what kind of animal would you rather be,

a deer,

a fox, or a hare? You have your choice now, but you may not have it

later." To make

a long story short, the story-teller made his choice of a hare; the old

man threw

the cord round him, struck him with the wand, and lo! a long-eared,

frisking hare

was skipping and jumping on the green. But it

wasn't for long; who but his wife called the hounds, and set them on

him. The hare

fled, the dogs followed. Round the field ran a high wall, so that run

as he might,

he couldn't get out, and mightily diverted were beggar and lady to see

him twist

and double. In vain

did he take refuge with his wife, she kicked him back again to the

hounds, until

at length the beggar stopped the hounds, and with a stroke of the wand,

panting

and breathless, the story-teller stood before them again. "And

how did you like the sport?" said the beggar. "It

might be sport to others," replied the story-teller looking at his

wife, "for

my part I could well put up with the loss of it." "Would

it be asking too much," he went on to the beggar, "to know who you are

at all, or where you come from, or why you take a pleasure in plaguing

a poor old

man like me?" "Oh!"

replied the stranger, "I'm an odd kind of good-for-little fellow, one

day poor,

another day rich, but if you wish to know more about me or my habits,

come with

me and perhaps I may show you more than you would make out if you went

alone." "I'm

not my own master to go or stay," said the story-teller, with a sigh. The stranger

put one hand into his wallet and drew out of it before their eyes a

well-looking

middle-aged man, to whom he spoke as follows: "By

all you heard and saw since I put you into my wallet, take charge of

this lady and

of the carriage and horses, and have them ready for me whenever I want

them." Scarcely

had he said these words when all vanished, and the story-teller found

himself at

the Foxes' Ford, near the castle of Red Hugh O'Donnell. He could see

all but none

could see him. O'Donnell

was in his hall, and heaviness of flesh and weariness of spirit were

upon him. "Go

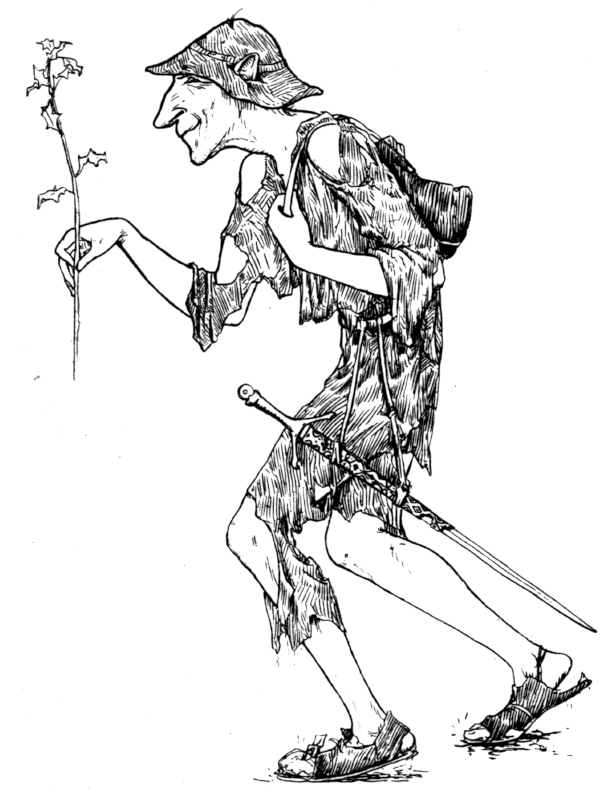

out," said he to his doorkeeper, "and see who or what may be coming." The

doorkeeper

went, and what he saw was a lank, grey beggarman; half his sword bared

behind his

haunch, his two shoes full of cold road-a-wayish water sousing about

him, the tips

of his two ears out through his old hat, his two shoulders out through

his scant

tattered cloak, and in his hand a green wand of holly.  "Save

you, O'Donnell," said the lank grey beggarman. "And

you likewise," said O'Donnell. "Whence come you, and what is your

craft?"

"I come from the outmost stream of earth,

From the glens where the white swans glide, A night in Islay, a night in Man, A night on the cold hillside." "It's

the great traveller you are," said O'Donnell. "Maybe

you've learnt something on the road." "I

am a juggler," said the lank grey beggarman, "and for five pieces of

silver

you shall see a trick of mine." "You

shall have them," said O'Donnell; and the lank grey beggarman took

three small

straws and placed them in his hand. "The

middle one," said he, "I'll blow away; the other two I'll leave." "Thou

canst not do it," said one and all. But the

lank grey beggarman put a finger on either outside straw and, whiff,

away he blew

the middle one. "'Tis

a good trick," said O'Donnell; and he paid him his five pieces of

silver. "For

half the money," said one of the chief's lads, "I'll do the same trick." "Take

him at his word, O'Donnell." The lad

put the three straws on his hand, and a finger on either outside straw

and he blew;

and what happened but that the fist was blown away with the straw. "Thou

art sore, and thou wilt be sorer," said O'Donnell. "Six

more pieces, O'Donnell, and I'll do another trick for thee," said the

lank

grey beggarman. "Six

shalt thou have." "Seest

thou my two ears! One I'll move but not t'other." "'Tis

easy to see them, they're big enough, but thou canst never move one ear

and not

the two together." The lank

grey beggarman put his hand to his ear, and he gave it a pull. O'Donnell

laughed and paid him the six pieces. "Call

that a trick," said the fistless lad, "any one can do that," and

so saying, he put up his hand, pulled his ear, and what happened was

that he pulled

away ear and head. "Sore

thou art; and sorer thou'lt be," said O'Donnell. "Well,

O'Donnell," said the lank grey beggarman, "strange are the tricks I've

shown thee, but I'll show thee a stranger one yet for the same money." "Thou

hast my word for it," said O'Donnell. With that

the lank grey beggarman took a bag from under his armpit, and from out

the bag a

ball of silk, and he unwound the ball and he flung it slantwise up into

the clear

blue heavens, and it became a ladder; then he took a hare and placed it

upon the

thread, and up it ran; again he took out a red-eared hound, and it

swiftly ran up

after the hare. "Now,"

said the lank grey beggarman; "has any one a mind to run after the dog

and

on the course?" "I

will," said a lad of O'Donnell's. "Up

with you then," said the juggler; "but I warn you if you let my hare be

killed I'll cut off your head when you come down." The lad

ran up the thread and all three soon disappeared. After looking up for

a long time,

the lank grey beggarman said: "I'm afraid the hound is eating the hare,

and

that our friend has fallen asleep." Saying

this he began to wind the thread, and down came the lad fast asleep;

and down came

the red-eared hound and in his mouth the last morsel of the hare. He struck

the lad a stroke with the edge of his sword, and so cast his head off.

As for the

hound, if he used it no worse, he used it no better. "It's

little I'm pleased, and sore I'm angered," said O'Donnell, "that a

hound

and a lad should be killed at my court." "Five

pieces of silver twice over for each of them," said the juggler, "and

their heads shall be on them as before." "Thou

shalt get that," said O'Donnell. Five pieces,

and again five were paid him, and lo! the lad had his head and the

hound his. And

though they lived to the uttermost end of time, the hound would never

touch a hare

again, and the lad took good care to keep his eyes open. Scarcely

had the lank grey beggarman done this when he vanished from out their

sight, and

no one present could say if he had flown through the air or if the

earth had swallowed

him up. He moved as wave tumbling

o'er wave

As whirlwind following whirlwind, As a furious wintry blast, So swiftly, sprucely, cheerily, Right proudly, And no stop made Until he came To the court of Leinster's King, He gave a cheery light leap O'er top of turret, Of court and city Of Leinster's King. Heavy

was the flesh and weary the spirit of Leinster's king. 'Twas the hour

he was wont

to hear a story, but send he might right and left, not a jot of tidings

about the

story-teller could he get. "Go

to the door," said he to his doorkeeper, "and see if a soul is in sight

who may tell me something about my story-teller." The

doorkeeper

went, and what he saw was a lank grey beggarman, half his sword bared

behind his

haunch, his two old shoes full of cold road-a-wayish water sousing

about him, the

tips of his two ears out through his old hat, his two shoulders out

through his

scant tattered cloak, and in his hand a three-stringed harp. "What

canst thou do?" said the doorkeeper. "I

can play," said the lank grey beggarman. "Never

fear," added he to the story-teller, "thou shalt see all, and not a man

shall see thee." When the

king heard a harper was outside, he bade him in. "It

is I that have the best harpers in the five-fifths of Ireland," said

he, and

he signed them to play. They did so, and if they played, the lank grey

beggarman

listened. "Heardst

thou ever the like?" said the king. "Did

you ever, O king, hear a cat purring over a bowl of broth, or the

buzzing of beetles

in the twilight, or a shrill tongued old woman scolding your head off?" "More

melodious to me," said the lank grey beggarman, "were the worst of

these

sounds than the sweetest harping of thy harpers." When the

harpers heard this, they drew their swords and rushed at him, but

instead of striking

him, their blows fell on each other, and soon not a man but was

cracking his neighbour's

skull and getting his own cracked in turn.

"Hang

the fellow who began it all," said he; "and if I can't have a story,

let

me have peace." Up came

the guards, seized the lank grey beggarman, marched him to the gallows

and hanged

him high and dry. Back they marched to the hall, and who should they

see but the

lank grey beggarman seated on a bench with his mouth to a flagon of ale. "Never

welcome you in," cried the captain of the guard, "didn't we hang you

this

minute, and what brings you here?" "Is

it me myself, you mean?" "Who

else?" said the captain. "May

your hand turn into a pig's foot with you when you think of tying the

rope; why

should you speak of hanging me?" Back they

scurried to the gallows, and there hung the king's favourite brother. Back they

hurried to the king who had fallen fast asleep. "Please

your Majesty," said the captain, "we hanged that strolling vagabond,

but

here he is back again as well as ever." "Hang

him again," said the king, and off he went to sleep once more. They did

as they were told, but what happened was that they found the king's

chief harper

hanging where the lank grey beggarman should have been. The captain

of the guard was sorely puzzled. "Are

you wishful to hang me a third time?" said the lank grey beggarman. "Go

where you will," said the captain, "and as fast as you please if you'll

only go far enough. It's trouble enough you've given us already." "Now

you're reasonable," said the beggarman; "and since you've given up

trying

to hang a stranger because he finds fault with your music, I don't mind

telling

you that if you go back to the gallows you'll find your friends sitting

on the sward

none the worse for what has happened." As he

said these words he vanished; and the story-teller found himself on the

spot where

they first met, and where his wife still was with the carriage and

horses. "Now,"

said the lank grey beggarman, "I'll torment you no longer. There's your

carriage

and your horses, and your money and your wife; do what you please with

them." "For

my carriage and my houses and my hounds," said the story-teller, "No,"

said the other. "I want neither, and as for your wife, don't think ill

of her

for what she did, she couldn't help it." "Not

help it! Not help kicking me into the mouth of my

own hounds! Not help casting me off for the sake of a beggarly old — " "I'm

not as beggarly or as old as ye think. I am Angus of the Bruff; many a

good turn

you've done me with the King of Leinster. This morning my magic told me

the difficulty

you were in, and I made up my mind to get you out of it. As for your

wife there,

the power that changed your body changed her mind. Forget and forgive

as man and

wife should do, and now you have a story for the King of Leinster when

he calls

for one;" and with that he disappeared. It's true

enough he now had a story fit for a king. From first to last he told

all that had

befallen him; so long and loud laughed the king that he couldn't go to

sleep at

all. And he told the story-teller never to trouble for fresh stories,

but every

night as long as he lived he listened again and he laughed afresh at

the tale of

the lank grey beggarman. |

t the

time when the Tuatha De Dannan held the sovereignty of Ireland, there

reigned in

Leinster a king, who was remarkably fond of hearing stories. Like the

other princes

and chieftains of the island, he had a favourite story-teller, who held

a large

estate from his Majesty, on condition of telling him a new story every

night of

his life, before he went to sleep. Many indeed were the stories he

knew, so that

he had already reached a good old age without failing even for a single

night in

his task; and such was the skill he displayed that whatever cares of

state or other

annoyances might prey upon the monarch's mind, his story-teller was

sure to send

him to sleep.

t the

time when the Tuatha De Dannan held the sovereignty of Ireland, there

reigned in

Leinster a king, who was remarkably fond of hearing stories. Like the

other princes

and chieftains of the island, he had a favourite story-teller, who held

a large

estate from his Majesty, on condition of telling him a new story every

night of

his life, before he went to sleep. Many indeed were the stories he

knew, so that

he had already reached a good old age without failing even for a single

night in

his task; and such was the skill he displayed that whatever cares of

state or other

annoyances might prey upon the monarch's mind, his story-teller was

sure to send

him to sleep. When the

king saw this, he thought it hard the harpers weren't content with

murdering their

music, but must needs murder each other.

When the

king saw this, he thought it hard the harpers weren't content with

murdering their

music, but must needs murder each other.