| Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2016 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

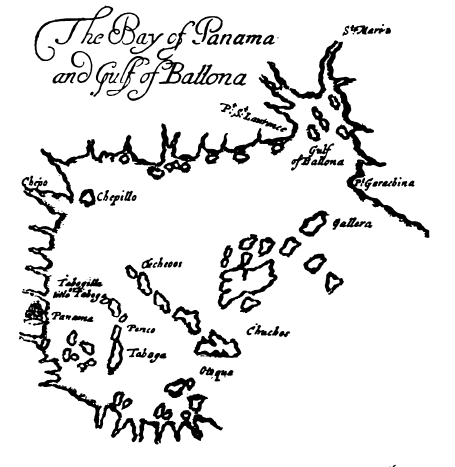

| CHAPTER VIII. Description of the state and condition of Panama, and the parts adjacent. What vessels they took while they blocked up the said Port. Captain Caron with seventy more returns house. Sawkins is chosen in chief THE famous city of Panama is situated in the latitude of nine degrees north. It stands in a deep bay, belonging to the South Sea. It is in form round, excepting only that part where it runs along the sea-side. Formerly it stood four miles more to the east, when it was taken by Sir Henry Morgan, as is related in the "History of the Buccaneers." But then being burnt, and three times more since that time by casualty, they removed it to the place where it now stands. Yet notwithstanding, there are some poor people still inhabiting the old town, and the cathedral church is still kept there, the beautiful building whereof makes a fair show at a distance, like that of St. Paul's in London. This new city of which I now speak, is much bigger than the old one, and is built for the most part of brick, the rest being of stone, and tiled. As for the churches belonging thereto, they are not as yet finished. These are eight in number, whereof the chief is called Santa Maria. The extent of the city comprehends better than a mile and a hall in length, and above a mile in breadth. The houses for the most part are three stories in height. It is well walled round about, with two gates belonging thereto, excepting only where a creek comes into the city, the which at high-water lets in barks, to furnish the inhabitants with all sorts of provisions and other necessaries. Here are always three hundred of the King's soldiers to garrison the city; besides which number, their militia, of all colours, are one thousand one hundred. But at the time that we arrived there, most of their soldiers were out of town, insomuch, that our coining put the rest into great consternation, they having had but one night's notice of our being in those seas. Hence we were induced to believe, that had we gone ashore, instead of fighting their ships, we had certainly rendered ourselves masters of the place; especially considering, that all their chief men were on board the Admiral; I mean, such as were undoubtedly the best soldiers. Round about the city, for the space of seven leagues, more or less, all the adjacent country is Savanna, as they call it in the Spanish language, that is to say, plain and level ground, as smooth as a sheet, for this is the signification of the word Savanna. Only here and there is to be seen a small spot of woody land, and everywhere this level ground is full of vacadas or beef stations,1 where whole droves of cows and oxen are kept, which serve as well as so many look-outs or watch towers, to descry if an enemy is approaching by land. The ground whereon the city stands, is very damp and moist, which renders the place of bad repute for the concern of health. The water is also very full of worms, and these are much prejudicial to shipping; which is the cause that the King's ships lie always at Lima, the capital city of Peru, unless when they come down to Panama to bring the King's plate, which is only at such times as the fleet of galleons comes from Old Spain to fetch and convey it thither. Here in one night after our arrival, we found worms of three-quarters of an inch in length, both in our bedclothes and other apparel. At the Island of Perico above-mentioned we seized in all five ships; of these, the first and biggest was named, as was said before, the Trinidad, and was a great ship, of the burden of four hundred tons. Her lading consisted of wine, sugar, sweetmeats (whereof the Spaniards in those hot countries make infinite use), skins, and soap. The second ship was of about three hundred tons burden, and not above half laden with bars of iron, which is one of the richest commodities that are brought into the South Sea. This vessel we burnt with the lading in her, because the Spaniards pretended not to want that commodity, and therefore would not redeem it. The third was laden with sugar, being of the burden of one hundred and fourscore tons, more or less. This vessel was given to be under the command of Captain Cook. The fourth was an old ship of sixty tons burden, which was laden with flour of meal. This ship we likewise burnt with her lading; esteeming both bottom and cargo, at that time, to be useless to us. The fifth was a ship of fifty tons, which, with a periagua, Captain Coxon took along with him when he left us. Within two or three days after our arrival at Panama, Captain Coxon being much dissatisfied with some reflections which had been made upon him by our company, determined to leave us, and return back to our ships in the Northern Seas, by the same way he came thither. Unto this effect, he persuaded several of our company, who sided most with him, and had had the chief hand in his election, to fall off from us, and bear him company in his journey or march, overland. The main cause of those reflections was his backwardness in the last engagement with the Armadilla, concerning which point some sticked not to defame, or brand, him with the note of cowardice. He drew off with him threescore and ten of our men, who all returned back with him in the ship and periagua above-mentioned, towards the mouth of the river of Santa Maria. In his company also went back the Indian King, Captain Antonio, and Don Andrceas, who, being old, desired to be excused from staying any longer with us. However, the King desired we would not be less vigorous in annoying their enemy and ours, the Spaniards, than if he were personally present with us. And to the intent we might see how faithfully he intended to deal with us, he at the same time recommended both his son and nephew to the care of Captain Sawk ins, who was now our newly-chosen General or Commander-in-Chief, in the absence of Captain Sharp. The two Armadilla ships which we took in the engagement we burnt also, saving no other thing of them both but their rigging and sails. With them also we burnt a small bark, which came into the port laden with fowls and poultry. On Sunday, which was April 25th, Captain Sharp with his bark and company came in and joined us again. His absence was occasioned by want of water, which forced him to bear up to the King's Islands. Being there, he found a new bark, which he at once took, and burnt his old one. This vessel did sail excellently well. Within a day or two after the arrival of Captain Sharp, came in likewise the people of Captain Harris, who were still absent. These had also taken another bark, and cut down the masts of their old one by the board, and thus without masts or sails turned away the prisoners they had taken in her. The next day we took in like manner another bark, which arrived from Nata, being laden with fowls, as before. In this bark we turned away all the meanest of the prisoners we had on board us. Having continued before Panama for the space of ten days, being employed in the affairs afore-mentioned, on May 2nd we weighed from the Island of Perico, and stood off to another island, distant two leagues farther from thence, called Tavoga. On this island stands a town which bears the same name, and consists of e hundred houses, more or less. The people of the town had all fled on seeing our vessels arrive. While we were here, some of our men being drunk on shore, happened to set fire to one of the houses, the which consumed twelve houses more before any could get ashore to quench it. To this island came several Spanish merchants from Panama, and sold us what commodities we needed, buying also of us much of the goods we had taken in their own vessels. They gave us likewise two hundred pieces of eight for each negro we could spare them, of such as were our prisoners. From this island we could easily see all the vessels that went out, or came into the Port of Panama; and here we took likewise several barks that were laden with fowls. Eight days after our arrival at Tavoga, we took a ship that was coming from Truxillo, and bound for Panama. I n this vessel we found two thousand jars of wine, fifty jars of gunpowder, and fifty-one thousand pieces of eight. This money had been sent from that city, to pay the soldiers belonging to the garrison of Panama. From the said prize we had information given us, that there was another ship coming from Lima with one hundred thousand pieces of eight more; which ship was to sail ten or twelve days after them, and which they said could not be long before she arrived at Panama. Within two days after this intelligence we took also another ship laden with flour from Truxillo, belonging to certain Indians, inhabitants of the same place, or thereabouts. This prize confirmed what the first had told us of that rich ship, and said, as the others had done before, that she would be there in the space of eight or ten days. Whilst we lay at Tavoga, the president, that is to say, the Governor of Panama, sent a message by some merchants to us, to know what we came for into those parts. To this message Captain Sawkins made answer, "That we came to assist the King of Darien, who was the true Lord of Panama and all the country thereabouts. And that since we were come so far, there was no reason but that we should have some satisfaction. So that if he pleased to send us five hundred pieces of eight for each man, and one thousand for each commander, and not any farther to annoy the Indians, but suffer them to use their own power and liberty, as became the true and natural lords of the country, that then we would desist from all further hostilities, and go away peaceably; otherwise that we should stay there, and get what we could, causing to them what damage was possible." By the merchants also that went and came to Panama, we understood, there lived then as Bishop of Panama one who had been formerly Bishop of Santa Martha, and who was prisoner to Captain Sawkins, when he took the said place about four or five years past. The Captain having received this intelligence, sent two loaves of sugar to the bishop as a present. On the next day the merchant who carried them, returning to Tavoga, brought to the Captain a gold ring for a retaliation of said present. And withal, he brought a message to Captain Sawkins from the President above-mentioned, to know farther of him, since we were Englishmen, "from whom we had our commission, and to whom he ought to complain for the damages we had already done them?" To this message Captain Sawkins sent back for answer, "That as yet all his company were not come together; but that when they were come up we would come and visit him at Panama, and bring our commissions on the muzzles of our guns, at which time he should read them as plain as the flame of gunpowder could make them." At this Island of Tavoga, Captain Sawkins would fain have stayed longer, to wait for the rich ship above-mentioned, that was coming from Peru; but our men were so importunate for fresh victuals, that no reason could rule them, nor their own interest persuade them to anything that might conduce to this purpose. Hereupon, on May 15th we weighed anchor, and sailed thence to the Island of Otoque. Being arrived there, we lay by it while our boat went ashore and fetched off fowls and hogs and other things necessary for sustenance. Here at Otoque I finished a draught, from point Garachine, to the bay of Panama, etc. Of this I may dare to affirm, that it is in general more correct and true than any the Spaniards have themselves, for which cause I have here inserted it, for the satisfaction of those that are curious in such things. From Otoque we sailed to the island of Cayboa, which is a place very famous for the pearl fishery thereabouts, and is at the distance of eight leagues from another place called Puebla Nueva, on the mainland. In our way to this island we lost two of our barks, the one whereof had fifteen men in her, and the other seven. Being arrived, we cast anchor at the said island. ____________________ 1 The word in the text is

stantions, evidently the Spanish word utancia. The Australian term

station has been substituted.  |