| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2019 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

The Boy Who Knew What The Birds Said Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

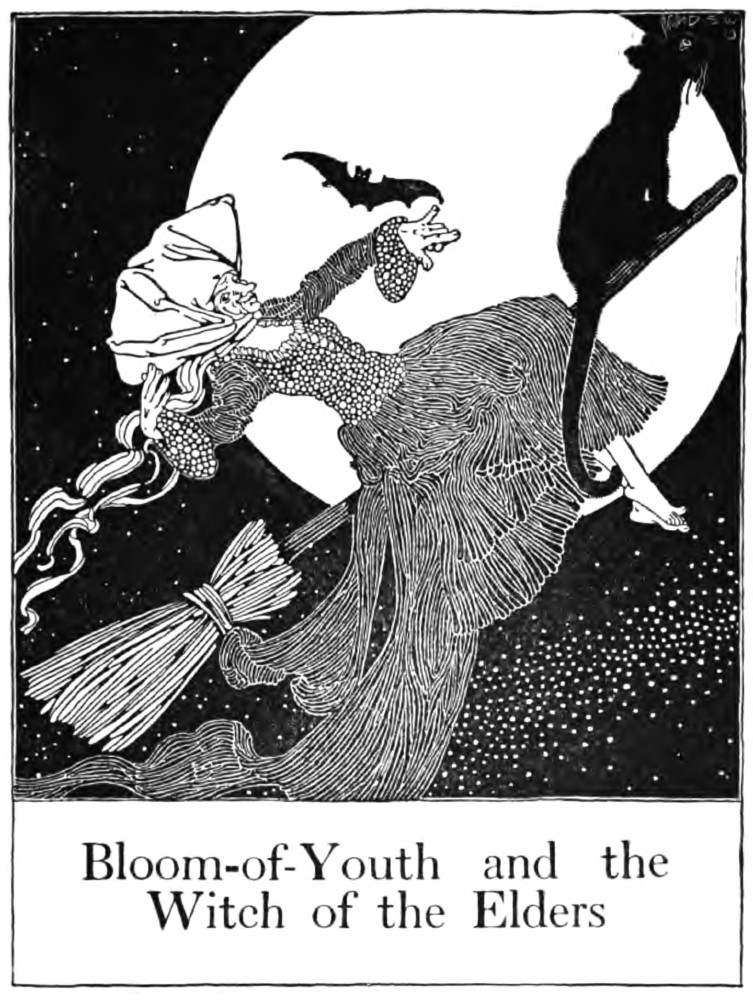

Bloom-of-Youth and the

Witch of the Elders

Bloom-of-youth was a young, young girl. But, young as she was, she would have to be married, her step-mother said. Then married she was while she was still little enough to walk through the doorway of her step-mother's hut without stooping her head. Her husband was a hunter and he took her to live in a hut at the edge of a wood. He was out hunting the whole of the day. Now what did Bloom-of-Youth do while she had the house to herself? Little enough indeed. She swept the floor and she washed the dishes and she laid them back on their shelf. Then she went to the well for pails of water. When she went out she stayed long, for first she would look into the well at her own image and then she would make a wreath of flowers and put it on her head and look at herself again. After that, maybe, she would delay to pick berries and eat them. Then she would go without hurrying along the path, singing to herself. —

'Said when he

saw

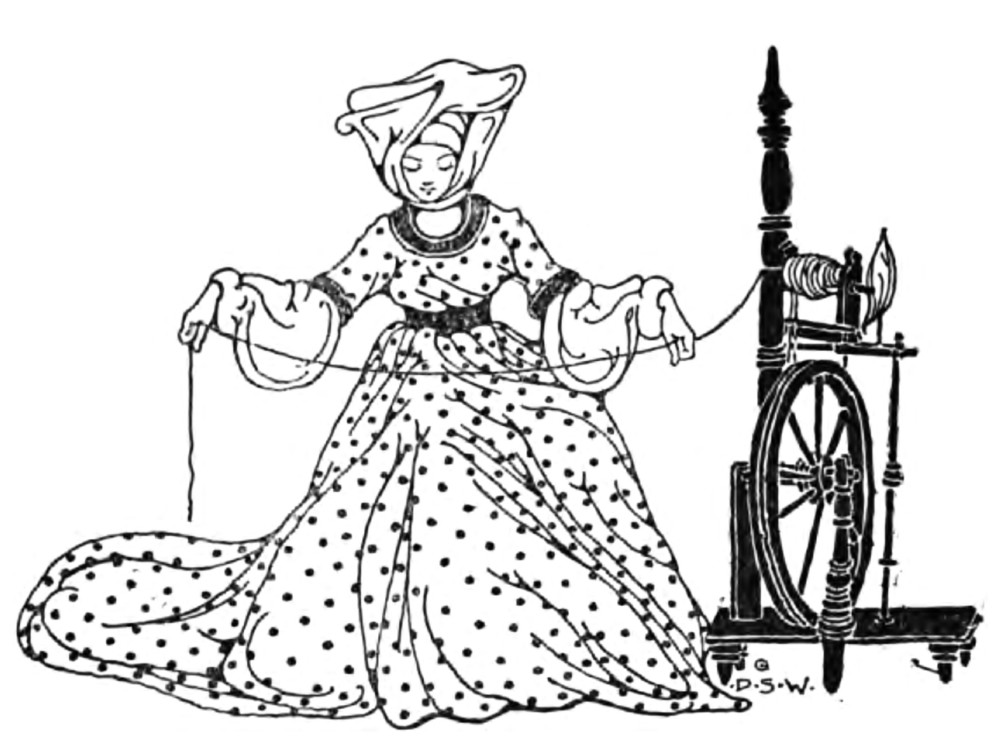

Me all in blue, "Who is the maid The sky must woo?" 'Said when he saw Me all in green, "Who is the maid The grass calls queen?"' When she would have got back to the hut the fire on the hearth would have gone out and she would have to light it again and then sweep the floor clear of the ashes that had blown upon it. After that she would have little time to do anything else except prepare a meal against the time when her husband would be back from his hunting. One morning her husband left his coat down on the bench. "My coat is torn; sew it for me," he said. Bloom-of-Youth said she would do that. But she did no more to the coat than take it up and leave it down again on the bench. The next day her husband said "My vest is torn too; have it and the coat sewn for me." He left the vest beside the coat and went out to his hunting. Bloom-of-Youth did nothing to the coat and nothing to the vest, and every day for a week her husband went out without coat or vest upon him. One day he put on his torn coat and his torn vest and went out to his hunting. When he came home that evening he had a bundle of wool with him. "Your step-mother," said he, "sends you this bundle of wool and she bids you spin it that there may be cloth for new clothes for me." "I will spin it," said Bloom-of-Youth. But the next day when her husband went away she did what she had always done before. She went to the well and she looked for long at her image; she put a wreath of flowers on her head and she looked at her image again; she picked berries and ate them; she went along the path without hurrying, singing to herself. — 'Said

when he saw

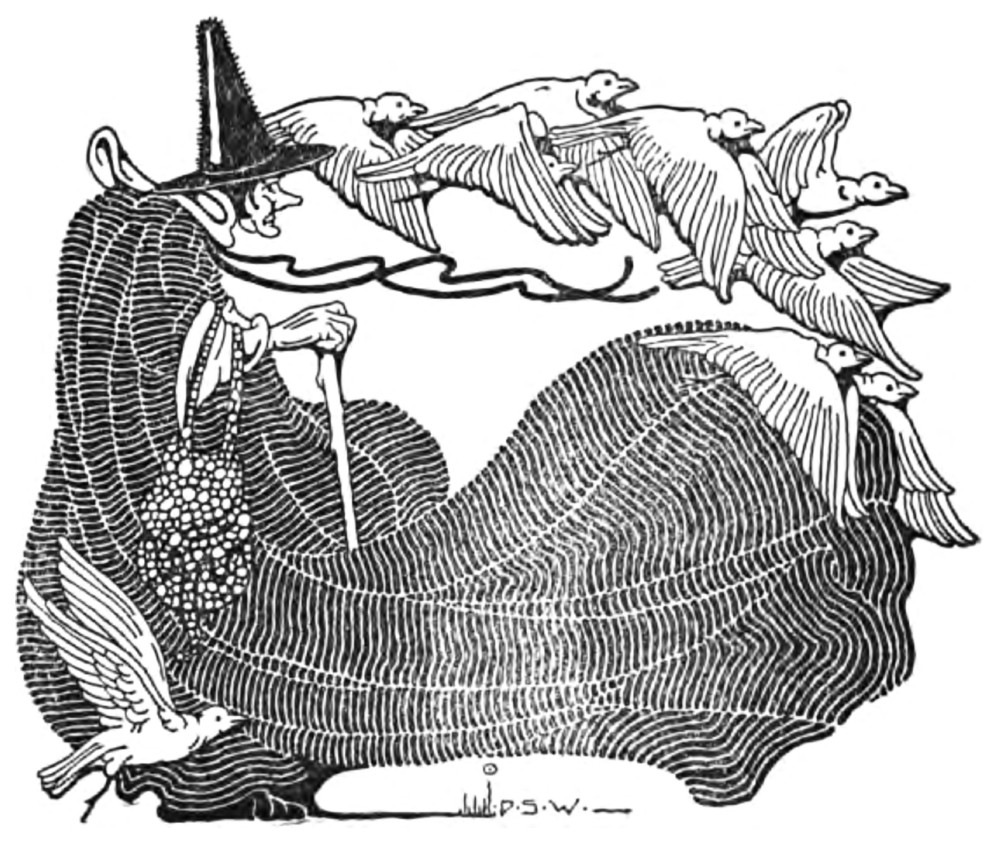

Me all in blue "Who is the maid The sky must woo?" 'Said when he saw Me all in green "Who is the maid The grass calls queen?"' She had to light the fire again when she came in and sweep away the ashes that had gathered on the floor and after she had done all that it was time to prepare the meal for the evening. But before her husband came home she took the spinning wheel out of the corner and put it near the light of the doorway. "I see," said her husband, "that you are going to spin the wool for my clothes." "I am when to-morrow comes," said Bloom-of-Youth. But the next day she did as she done every day and no wool was spun. The day after she put wool on the wheel and gave it a few turns. In a week from that evening she had one ball of thread spun. "Your step-mother bids me ask you how much of the wool have you spun?" said her husband to her one evening. Bloom-of-Youth was so much afraid that her husband would send her to her step-mother through the dark, dark wood, that she said "I have spun many balls." "Your step-mother bade me count the balls you have spun," said her husband. "I will go up to the loft and throw them down to you and then you will throw them back to me and we will count them that way," said Bloom-of-Youth. She went up to the loft and she flung down the ball she had spun. "One," said her husband, and he threw it back to her. She flung him the ball again.  "Two," said her husband, and he flung it back to her. Then he said "three," and then "four," and then "five," and so on until he had counted twelve. "You have done well," said he, "and now before the week is out take the twelve balls to your step-mother's house and she will weave the thread into cloth for clothes for me." Bloom-of-Youth was greatly frightened. To her step-mother's house she would have to go with a dozen balls of thread in a few days. The next day she hurried back from the well and she sat at her wheel before the door spinning and spinning. But, do her best, she could not get a good thread spun in the long length of the day. And while she was spinning and spinning and getting her thread knotted and broken a black and crooked woman came and stood before the door. "You're spinning hard I see," said she to Bloom-of-Youth. Bloom-of-Youth gave her no answer but put her head against the wheel and cried and cried. "And what would you say," said the black and crooked woman, "if I took the bundle of wool from you now and brought it back to you to-morrow spun into a dozen balls of thread?" "It is not what I would say; it is what I should give you," said Bloom-of-Youth. "Give me!" said the black and crooked woman. "What could you give me?" But as she said it she gave Bloom-of-Youth a baleful look from under her leafy eyebrows. "No, no, you need give me nothing for spinning the wool for you. All that I'll ask from you is that you tell me my name within a week from this day." "It will be easy to find out her name within a week," said Bloom-of-Youth to herself. She took the bundle of wool out of the basket and gave it to her. The black and crooked woman put the wool under her arm and then she lifted up her stick and shook it at Bloom-of-Youth. "And if you don't find out my name within a week you will have to give me your heart's blood — a drop of heart's blood for every ball of wool I spin for you." The hag went away then. Bloom-of-Youth was greatly frightened, but after a while she said to herself "I need not be afraid, for in a week I'll surely find out the name of the black and crooked woman who can't live far from this." The next day the hag came to the door and left twelve balls of wool on the bench outside the house. "In a week, in a week," said she, "you'll have my name or I'll have twelve drops of your heart's blood to make the leaves of my Elder Tree fresh and fine." Bloom-of-Youth went with the twelve balls of wool to her step-mother's house, and every person she met on the way she asked if he or she knew the name of the black and crooked woman. But no one could tell her the hag's real name. All they could tell was that she was the Witch of the Elders and that she lived beside the Big Stones that were at the other side of the wood. Bloom-of-Youth was afraid: her face lost its color and her eyes grew wide and her heart would beat from one side of her body to the other. And every day the Witch of the Elders would come to the door and say "Have you my name yet, Bloom-of-Youth, have you my name yet? Two days gone, five to come on; three days gone, four to come on; four days gone, three to come on; five days gone, two to come on." Six days went by and on the seventh she would have to go to the Big Stones at the other side of the wood and let the Witch of the Elders take twelve drops of her heart's blood. The night before the week's end her husband, when he sat down by the fire said "I saw something and I heard something very strange when I was at the other side of the wood this evening." "What was it you saw?" said Bloom-of-Youth. "Lights were all round the Big Stones and there was a noise of spinning inside the ring they make. That's what I saw." "And what was it you heard?" said Bloom-of-Youth. "Someone singing to the wheels," said her husband. "And this is what I heard sung. — Spin, wheel,

spin; sing, wheel, sing;

Every stone in my yard, spin, spin, spin; The thread is hers, the wool is mine; Twelve drops from her heart will make my leaves shine! How little she knows, the foolish thing, That my name is Bolg and Curr and Carr, That my name is Lurr and Lappie. "O sing that song again," said Bloom-of-Youth, "Sing that song again." Her husband sang it again, and Bloom-of-Youth went to bed, singing to herself. — My name is

Bolg and

Curr and Carr,

My name is Lurr and Lappie. The next day as soon as her husband had gone to his hunting Bloom-of-Youth went through the wood and towards the Big Stones that were at the other side of it. And as she went through the wood she sang. — Spin, wheel,

spin;

sing, wheel, sing;

Every branch on the tree, spin, spin, spin; The wool is hers, the thread is fine; For loss of my heart's blood I'll never dwine; Her name is Bolg and Curr and Carr, Her name is Lurr and Lappie. She went singing until she was through the wood and near the Big Stones. She went within the circle. There, besides a flat stone that was on the ground, she saw the black and crooked old woman. "You have come to me, Bloom-of-Youth," said she. "Do you see the hollow that is in this stone? It is into this hollow that the drops of your heart's blood will have to run." "The drops of my heart's blood may remain my own." "No, no, they won't remain your own any longer than when it is plain you can't tell my name." "Is it Bolg?" said Bloom-of-Youth. "Bolg is one of my names," screamed the Witch of the Elders, "but one of my names won't let you go free." "Is it Curr?" "Curr is another of my names, but two of my names won't let you go free." "Is it Carr?" "Carr is another of my names, but three of my names will not let you go free." "I know your other names too," said Bloom-of-Youth. "Say them, say them," screamed the Witch of the Elders. But when she tried to think of them Bloom-of-Youth found that the last two names had gone out of her mind. Not for all the drops that were in her heart could she remember them. "No, no, you can't say them," said the Witch of the Elders. "And now bend your breast over the hollow in the stone. I'll let out twelve drops of your heart's blood with my pointed rod. Bend your breast over the hollow." But just as the Witch was dragging her to the stone a robin began to sing on a branch outside the Stones. It was the same tune as Bloom-of-Youth had sung her song to as she went through the wood. Now all the words in her song came back to her. — Spin, wheel,

spin;

sing, wheel, sing;

Every branch on the tree, spin, spin, spin; The wool is hers, the thread is mine; For loss of my heart's blood I'll never dwine! Her name is Bolg and Curr and Carr, Her name is Lurr and Lappie.  But just as the Witch was dragging her to the stone a robin began to sing. She said the last two names and as she did the Witch of the Elders screamed and ran behind the stones. Bloom-of-Youth saw no more of her. That evening her husband brought home the web of cloth that her step-mother had woven. The next day Bloom-of-Youth began to make clothes for him out of it. Never again did she make delays at the well but she came straight home with her pails of water. The fire was always clear upon the hearth and she had never to light it the second time and then sweep away the ashes that had gathered on the floor. She made good clothes for her husband out of the web of cloth her step-mother had woven. And every evening she spun on her wheel and there was never a time afterwards when she had not a dozen balls of thread in the house. The wool is hers and the thread is mine; For loss of my heart's blood I never will dwine, And I throw my ball over to you. It was the Woodpecker that told this story to the Boy Who Knew What the Birds Said.  |