|

Web and Book design, Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2005 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Best Stories to Tell to Children Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

An old legend says that

there was once a king named Robert of Sicily, who was brother to the

great Pope

of Rome and to the Emperor of Allemaine. He was a very selfish king,

and very

proud; he cared more for his pleasures than for the needs of his

people, and

his heart was so filled with his own greatness that he had no thought

for God. One day, this proud king was

sitting in his place at church, at vesper service; his courtiers were

about

him, in their bright garments, and he himself was dressed in his royal

robes.

The choir was chanting the Latin service, and as the beautiful voices

swelled

louder, the king noticed one particular verse which seemed to be

repeated again

and again. He turned to a learned clerk at his side and asked what

those words

meant, for he knew no Latin. "They mean, 'He hath

put down the mighty from their seat, and hath exalted them of low

degree'"

answered the clerk. "It is well the words

are in Latin, then," said the king angrily, "for they are a lie.

There is no power on earth or in heaven which can put me down from my

seat!" And he sneered at the beautiful singing, as he leaned back in

his

place. Presently the king fell

asleep, while the service vent on. He slept deeply and long. When he

awoke the

church was dark and still, and he was all alone. He, the king, had been

left

alone in the church, to awake in the dark! He was furious with rage and

surprise, and, stumbling through the dim aisles, he reached the great

doors and

beat at them, madly, shouting for his servants. The old sexton heard some

one shouting and pounding in the church, and thought it was some

drunken

vagabond who had stolen in during the service. He came to the door with

his

keys and called out, "Who is there? " "Open! open! It is I,

the king!" came a hoarse. angry voice from within. "It is a crazy

man," thought the sexton; and he was frightened. He opened the doors

carefully

and stood back, peering into the darkness. Out past him rushed the

figure of a

man in tattered, scanty clothes, with unkempt hair and white, wild

face. The

sexton did not know that he had ever seen him before, but he looked

long after

him, wondering at his wildness and his haste. In his fluttering rags,

without hat or cloak, not knowing what strange thing had happened to

him, King

Robert rushed to his palace gates, pushed aside the startled servants,

and

hurried, blind with rage, up the wide stair and through the great

corridors,

toward the room where he could hear the sound of his courtiers'

voices. Men

and women servants tried to stop the ragged man, who had somehow got

into the

palace, but Robert did not even see them as he fled along. Straight to

the

open doors of the big banquet hall he made his way, and into the midst

of the

grand feast there. The great hall was filled

with lights and flowers; the tables were set with everything that is

delicate

and rich to eat; the courtiers, in their gay clothes, were laughing and

talking; and at the head of the feast, on the king's own throne, sat a

king.

His face, his figure, his voice, were exactly like Robert of Sicily; no

human

being could have told the difference; no one dreamed that he was not

the king.

He was dressed in the king's royal robes, he wore the royal crown, and

on his

hand was the king's own ring. Robert of Sicily, half naked, ragged,

without a

sign of his kingship on him, stood before the throne and stared with

fury at

this figure of himself. The king on the throne

looked at him. "Who art thou, and what dost thou here?" he asked. And

though his voice was just like Robert's own, it had something in it

sweet and

deep, like the sound of bells. "I am the king!"

cried Robert of Sicily. "I am the king, and you are an impostor!" The courtiers started from

their seats and drew their swords. They would have killed the crazy man

who

insulted their king; but he raised his hand and stopped them, and with

his eyes

looking into Robert's eyes he said, "Not the king; you shall be the

king's

jester! You shall wear the cap and bells, and make laughter for my

court. You

shall be the servant of the servants, and your companion shall be the

jester's

ape." With shouts of laughter, the

courtiers drove Robert of Sicily from the banquet hall; the

waiting-men, with

laughter, too, pushed him into the soldiers' hall; and there the pages

brought

the jester's wretched ape, and put a fool's cap and bells on Roberts'

head. It

was like a terrible dream; he could not believe it true, he could not

understand what had happened to him. And when he woke next morning, he

believed

it was a dream, and that he was king again. But as he turned his head,

he felt

the coarse straw under his cheek instead of the soft pillow, and he

saw that

he was in the stable, with the shivering ape by his side. Robert of

Sicily was

a jester, and no one knew him for the king. Three long years passed.

Sicily was happy and all things went well under the king, who was not

Robert.

Robert was still the jester, and his heart was harder and bitterer with

every

year. Many times, during the three years, the king, who had his face

and voice,

had called him to himself, when none else could hear, and had asked him

the one

question, "Who art thou?" And each time that he asked it his eyes

looked into Robert's eyes, to find his heart. But each time Robert

threw back

his head and answered, proudly, "I am the king!" And the king's eyes

grew sad and stern. At the end of three years,

the Pope bade the Emperor of Allemaine and the King of Sicily, his

brothers,

to a great meeting in his city of Rome. The King of Sicily went, with

all his

soldiers and courtiers and servants, -- a great procession of horsemen

and

footmen. Never had been a gayer sight than the grand train, men in

bright

armor, riders in wonderful cloaks of velvet and silk, servants,

carrying

marvelous presents to the Pope. And at the very end rode Robert, the

jester.

His horse was a poor old thing, many colored, and the ape rode with

him. Every

one in the villages through which they passed ran after the jester, and

pointed

and laughed. The Pope received his

brothers and their trains in the square before Saint Peter's. With

music and

flags and flowers he made the King of Sicily welcome, and greeted him

as his brother.

In the midst of it, the jester broke through the crowd and threw

himself before

the Pope. "Look at me!" he cried; "I am your brother, Robert of

Sicily! This man is an impostor, who has stolen my throne. I am Robert,

the

king!" The Pope looked at the poor

jester with pity, but the Emperor of Allemaine turned to the King of

Sicily,

and said, "Is it not rather dangerous, brother, to keep a madman as

jester?" And again Robert was pushed back among the serving-men. It was Holy Week, and the

king and the Emperor, with all their trains, went every day to the

great services

in the cathedral. Something wonderful and holy seemed to make all these

services more beautiful than ever before. All the people of Rome felt

it: it

was as if the presence of an angel were there. Men thought of God, and

felt his

blessing on them. But no one knew who it was that brought the beautiful

feeling. And when Easter Day came, never had there been so lovely, so

holy a

day: in the great churches, filled with flowers, and sweet with

incense, the

kneeling people listened to the choirs singing, and it was like the

voices of

angels; their prayers were more earnest than ever before, their praise

more

glad; there was something heavenly in Rome. Robert of Sicily went to the

services with the rest, and sat in the humblest place with the

servants. Over

and over again he heard the sweet voices of the choirs chant the Latin

words he

had heard long ago: "He hath put down the mighty from their seat, and

hath

exalted them of low degree." And at last, as he listened, his heart

was

softened. He, too, felt the strange blessed presence of a heavenly

power. He

thought of God, and of his own wickedness; he remembered how happy he

had been,

and how little good he had done; he realized that his power had not

been from

himself, at all. On Easter night, as he crept to his bed of straw, he

wept, not

because he was so wretched, but because he had not been a better king

when

power was his. At last all the festivities

were over, and the King of Sicily went home to his own land again, with

his

people. Robert the jester came home too. On the day of their

home-coming, there was a special service in the royal church, and even

after

the service was over for the people the monks held prayers of

thanksgiving and

praise. The sound of their singing came softly in at the palace

windows. In

the great banquet room, the king sat, wearing his royal robes and his

crown,

while many subjects came to greet him. At last, he sent them all away,

saying

he wanted to be alone; but he commanded the jester to stay. And when

they were

alone together the king looked into Robert's eyes, as he had done

before, and

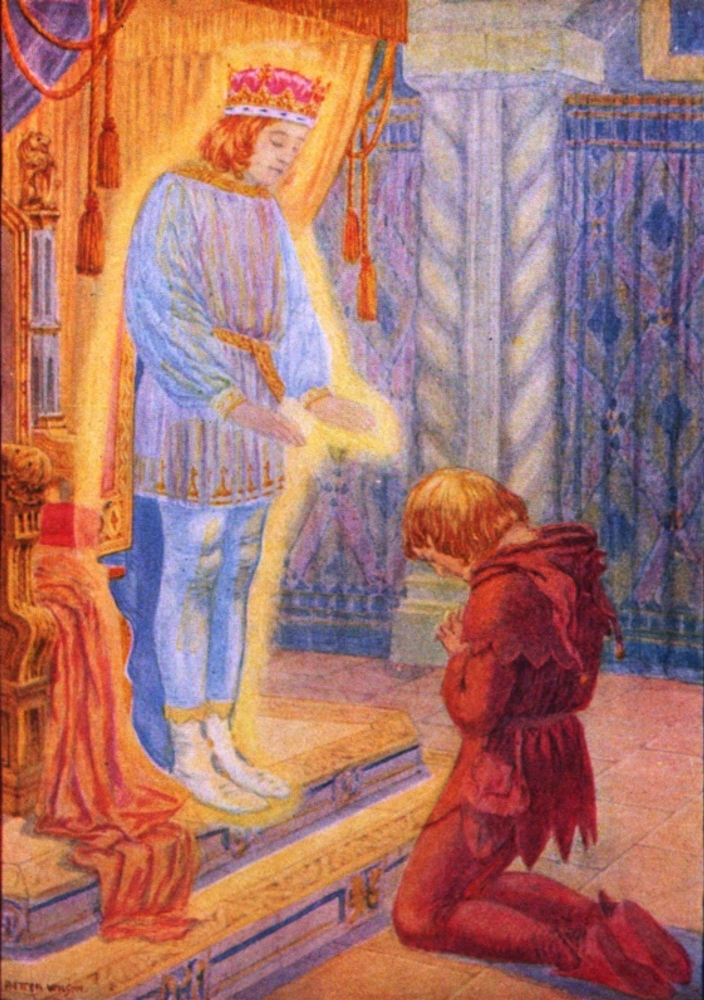

said, softly, "Who art thou?" Robert of Sicily bowed his

head. "Thou knowest best," he said, "I only know that I have

sinned." As he spoke, he heard the

voices of the monks singing, "He hath put down the mighty from their

seat," -- and his head sank lower. But suddenly the music seemed to

change; a wonderful light shone all about. As Robert raised his eyes,

he saw

the face of the king smiling at him with a radiance like nothing on

earth, and

as he sank to his knees before the glory of that smile, a voice sounded

with

the music, like a melody throbbing on a single string: -- "I am an angel, and

thou art the king!" Then Robert of Sicily was

alone. His royal robes were upon him once more; he wore his crown and

his royal

ring. He was king. And when the courtiers came back they found their

king

kneeling by his throne absorbed in silent prayer.  ROBERT OF SICILY BOWED HIS HEAD You know, dears, in the old

countries there are many fine stories about things which happened so

very long

ago that nobody knows exactly how much of them is true. Ireland is like

that.

It is so old that even as long ago as four thousand years it had people

who dug

in the mines, and knew how to weave cloth and to make beautiful

ornaments out

of gold, and who could fight and make laws; but we do not know just

where they

came from, nor exactly how they lived. These people left us some

splendid

stories about their kings, their fights, and their beautiful women; but

it all

happened such a long time ago that the stories are mixtures of things

that

really happened and what people said about them, and we don't know

just which

is which. The stories are called legends.

One of the prettiest legends is the story I am going to tell

you about the

Dagda's harp. It is said that there were

two quite different kinds of people in Ireland: one set of people with

long

dark hair and dark eyes, called Fomorians -- they carried long slender

spears

made of golden bronze when they fought -- and another race of people

who were

golden-haired and blue-eyed, and who carried short, blunt, heavy

spears of

dull metal. The golden-haired people had

a great chieftain who was also a kind of high priest, who was called

the Dagda.

And this Dagda had a wonderful magic harp. The harp was beautiful to

look upon,

mighty in size, made of rare wood, and ornamented with gold and jewels;

and it

had wonderful music in its strings, which only the Dagda could call

out. When

the men were going out to battle, the Dagda would set up his magic harp

and

sweep his hand across the strings, and a war song would ring out which

would

make every warrior buckle on his armor, brace his knees, and shout,

"Forth

to the fight!" Then, when the men came back from the battle, weary and

wounded, the Dagda would take his harp and strike a few chords, and as

the

magic music stole out upon the air, everyman forgot his weariness and

the smart of his wounds, and thought of the honor he had won, and of

the comrade

who had died beside him, and of the safety of his wife and children.

Then the

song would swell out louder, and every warrior would remember only the

glory he

had helped win for the king; and each man would rise at the great

table, his

cup in his hand, and shout, "Long live the King!" There came a time when the

Fomorians and the golden-haired men were at war; and in the midst of a

great

battle, while the Dagda's hall was not so well guarded as usual, some

of the

chieftains of the Fomorians stole the great harp from the wall, where

it hung,

and fled away with it. Their wives and children and some few of their

soldiers

went with them, and they fled fast and far through the night, until

they were a

long way from the battlefield. Then they thought they were safe, and

they

turned aside into a vacant castle, by the road, and sat down to a

banquet, hanging

the stolen harp on the wall. The Dagda, with two or three

of his warriors, had followed hard on their track. And while they were

in the

midst of their banqueting, the door was burst open, and the Dagda stood

there,

with his men. Some of the Fomorians sprang to their feet, but before

any of

them could grasp a weapon, the Dagda called out to his harp on the

wall,

"Come to me, O my harp!" The great harp recognized

its master's voice, and leaped from the wall. Whirling through the

hall,

sweeping aside and killing the men who got in its way, it sprang to its

master's hand. And the Dagda took his harp and swept his hand across

the

strings in three great, solemn chords. The harp answered with the magic

Music

of Tears. As the wailing harmony smote upon the air, the women of the

Fomorians

bowed their heads and wept bitterly, the strong men turned their faces

aside,

and the little children sobbed. Again the Dagda touched the strings, and this time the magic Music of Mirth leaped from the harp. And when they heard that Music of Mirth, the young warriors of the Fomorians began to laugh; they laughed till the cups fell from their grasp, and the spears dropped from their hands, while the wine flowed from the broken bowls; they laughed until their limbs were helpless with excess of glee.

Once more the Dagda touched

his harp, but very, very softly. And now a music stole forth as soft as

dreams,

and as sweet as joy: it was the magic Music of Sleep. When they heard

that,

gently, gently, the Fomorian women bowed their heads in slumber; the

little

children crept to their mothers' laps; the old men nodded; and the

young

warriors drooped in their seats and closed their eyes: one after

another all

the Fomorians sank into sleep. When they were all deep in

slumber, the Dagda took his magic harp, and he and his golden-haired

warriors

stole softly away, and came in safety to their own homes again. A long time ago, there was a

boy named David, who lived in a country far east of this. He was good

to look

upon, for he had fair hair and a ruddy skin; and he was very strong and

brave

and modest. He was shepherd-boy for his father, and all day -- often

all night

-- he was out in the fields, far from home, watching over the sheep. He

had to

guard them from wild animals, and lead them to the right pastures, and

care for

them. By and by, war broke out

between the people of David's country and a people that lived near at

hand; these

men were called Philistines, and the people of David's country were

named

Israel. All the strong men of Israel went up to the battle, to fight

for their

king. David's three older brothers went, but he was only a boy, so he

was left

behind to care for the sheep, After the brothers had been gone some

time, David's father longed very much to

hear from

them, and to know if they were safe; so he sent for David, from the

fields, and

said to him, "Take now for thy brothers an ephah of this parched corn,

and

these ten loaves, and run to the camp, where thy brothers are; and

carry these

ten cheeses to the captain of their thousand, and see how thy brothers

fare,

and bring me word again." [An ephah is about three pecks.] David rose early in the

morning, and left the sheep with a keeper, and took the corn and the

loaves and

the cheeses, as his father had commanded him, and went to the camp of

Israel. The camp was on a mountain;

Israel stood on a mountain on the one side, and the Philistines stood

on a

mountain on the other side; and there was a valley between them. David

came to

the place where the Israelites were, just as the host was going forth

to the

fight, shouting for the battle. So he left his gifts in the hands of

the keeper

of the baggage, and ran into the army, amongst the soldiers, to find

his

brothers. When he found them, he

saluted them and began to talk with them. But while he was asking them

the questions his father had commanded, there arose a great shouting

and tumult

among the Israelites, and men came running back from the front line of

battle;

everything became confusion. David looked to see what the trouble was,

and he

saw a strange sight: on the hillside of the Philistines, a warrior was

striding

forward, calling out something in a taunting voice; he was a gigantic

man, the

largest David had ever seen, and he was dressed in armor, that shone in

the

sun: he had a helmet of brass upon his head, and he was armed with a

coat of

mail, and he had greaves of brass upon his legs, and a target of brass

between

his shoulders; his spear was so tremendous that the staff of it was

like a

weaver's beam, and his shield so great that a man went before him, to

carry it. "Who is that?"

asked David. "It is Goliath, of

Gath, champion of the Philistines," said the soldiers about. "Every

day, for forty days, he has come forth, so, and challenged us to send a

man

against him, in single combat; and since no one dares to go out against

him

alone, the armies cannot fight." [That was one of the laws of warfare

in

those times.] "What!" said

David, "does none dare go out against him?" As he spoke, the giant stood

still, on the hillside opposite the Israelitish host, and shouted his

challenge,

scornfully. He said, "Why are ye come out to set your battle in array?

Am

I not a Philistine, and ye servants of Saul? Choose you a man for you,

and let

him come down to me. If he be able to fight with me, and to kill me,

then will

we be your servants; but if I prevail against him, and kill him, then

shall ye

be our servants, and serve us. I defy the armies of Israel this day;

give me a

man, that we may fight together!" When King Saul heard these

words, he was dismayed, and all the men of Israel, when they saw the

man, fled

from him and were sore afraid. David heard them talking among

themselves,

whispering and murmuring. They were saying, "Have ye seen this man

that

is come up? Surely if any one killeth him that man will the king make

rich;

perhaps he will give him his daughter in marriage, and make his family

free in

Israel!" David heard this, and he

asked the men if it were so. It was surely so, they said. "But," said David,

"who is this Philistine, that he should defy the armies of the living

God?" And he was stirred with anger. Very soon, some of the

officers told the king about the youth who was asking so many

questions, and

who said that a mere Philistine should not be let defy the armies of

the living

God. Immediately Saul sent for him. When David came before Saul, he

said to the

king, "Let no man's heart fail because of him; thy servant will go and

fight with this Philistine." But Saul looked at David,

and said, "Thou art not able to go against this Philistine, to fight

with

him, for thou art but a youth, and he has been a man of war from his

youth." Then David said to Saul,

"Once I was keeping my father's sheep, and there came a lion and a

bear,

and took a lamb out of the flock; and I went out after the lion, and

struck

him, and delivered the lamb out of his mouth, and when he arose against

me, I

caught him by the beard, and struck him, and slew him! Thy servant

slew both

the lion and the bear; and this Philistine shall be as one of them,

for he

hath defied the armies of the living God. The Lord, who delivered me

out of the

paw of the lion and out of the paw of the bear, he will deliver me out

of the

hand of this Philistine." "Go," said Saul,

"and the Lord be with thee!" And he armed David with his own armor,

-- he put a helmet of brass upon his head, and armed him with a coat of

mail.

But when David girded his sword upon his armor, and tried to walk, he

said to

Saul, "I cannot go with these, for I am not used to them." And he put

them off. Then he took his staff in

his hand and went and chose five smooth stones out of the brook, and

put them

in a shepherd's bag which he had; and his sling was in his hand; and he

went

out and drew near to the Philistine. And the Philistine came on

and drew near to David; and the man that bore his shield went before

him. And

when the Philistine looked about and saw David, he disdained him, for

David was

but a boy, and ruddy, and of a fair countenance. And he said to David,

"Am

I a dog, that thou comest to me with a cudgel?" And with curses he

cried

out again, "Come to me, and I will give thy flesh unto the fowls of the

air, and to the beasts of the field." But David looked at him, and

answered, "Thou comest to me with a sword, and with a spear, and with a

shield; but I come to thee in the name of the Lord of hosts, the God of

the

armies of Israel, whom thou hast defied. This day will the Lord deliver

thee

into my hands; and I will smite thee, and take thy head from thee, and

I will

give the carcasses of the host of the Philistines this day unto the

fowls of

the air, and to the wild beasts of the earth, that all the earth may

know that

there is a God in Israel! And all this assembly shall know that the

Lord saveth

not with sword and spear; for the battle is the Lord's, and he will

give you

into our hands." And then, when the

Philistine arose and came, and drew nigh to meet David, David hasted,

and ran

toward the army to meet the Philistine. And when he was a little way

from him,

he put his hand in his bag, and took thence a stone, and put it in his

sling,

and slung it, and smote the Philistine in the forehead, so that the

stone sank

into his forehead; and he fell on his face to the earth. Then, when the Philistines

saw that their champion was dead, they fled. But the army of Israel

pursued

them, and victory was with the men of Israel. And after the battle, David

was taken to the king's tent, and made a captain over many men; and he

went no

more to his father's house, to herd the sheep, but became a man, in the

king's

service. THE END

|

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2005

(Return to Web Text-ures)