THE LITTLE JACKALS AND THE

LION Once there was a great big

jungle; and in the jungle there was a great big Lion; and the Lion was

king of

the jungle. Whenever he wanted anything to eat, all he had to do was to

come up

out of his cave in the stones and earth, and roar. When he had roared a

few

times all the little people of the jungle were so frightened that they

came

out of their holes and hiding-places and ran, this way and that, to

get away.

Then, of course, the Lion could see where they were. And he pounced on

them,

killed them, and gobbled them up.

He did this so often that at

last there was not a single thing left alive in the jungle besides the

Lion,

except two little Jackals, -- a little father Jackal and a little

mother

Jackal.

They had run away so many

times that they were quite thin and very tired, and they could not run

so fast

any more. And one day the Lion was so near that the little mother

Jackal grew

frightened; she said, --

"Oh, Father Jackal,

Father Jackal! I b'lieve our time has come! the Lion will surely catch

us this

time!"

"Pooh, nonsense,

mother! " said the little father Jackal. "Come, we'll run on a

bit!"

And they ran, ran, ran very

fast, and the Lion did not catch them that time.

But at last a day came when

the Lion was nearer still and the little mother Jackal was frightened

about to

death.

"Oh, Father Jackal,

Father Jackal!" she cried; " I'm sure our time has come! The Lion 's

going to eat us this time!"

"Now, mother, don't you

fret," said the little father Jackal; "you do just as I tell you, and

it will be all right."

Then what did those cunning

little Jackals do but take hold of hands and run up towards the Lion,

as if

they had meant to come all the time. When he saw them coming he stood

up, and

roared in a terrible voice, --

"You miserable little

wretches, come here and be eaten, at once! Why didn’t you come before?"

The father Jackal bowed very

low.

"Indeed, Father

Lion," he said, "we meant to come before; we knew we ought to come

before; and we wanted to come before; but every time we started to

come, a

dreadful great lion came out of the woods and roared at us, and

frightened us

so that we ran away."

"What do you

mean?" roared the Lion. "There 's no other lion in this jungle, and

you know it!"

"Indeed, indeed, Father

Lion," said the little Jackal, "I know that is what everybody thinks;

but indeed and indeed there is another lion! And he is as much bigger

than you

as you are bigger than I! His face is much more terrible, and his roar

far, far

more dreadful. Oh, he is far more fearful than you!"

At that the Lion stood up

and roared so that the jungle shook.

"Take me to this

lion," said he; "I'll eat him up and then I'll eat you up."

The little Jackals danced on

ahead, and the Lion stalked behind. They led him to a place where there

was a

round, deep well of clear water. They went round on one side of it, and

the

Lion stalked up to the other.

"He lives down there,

Father Lion!" said the little Jackal. "He lives down there!"

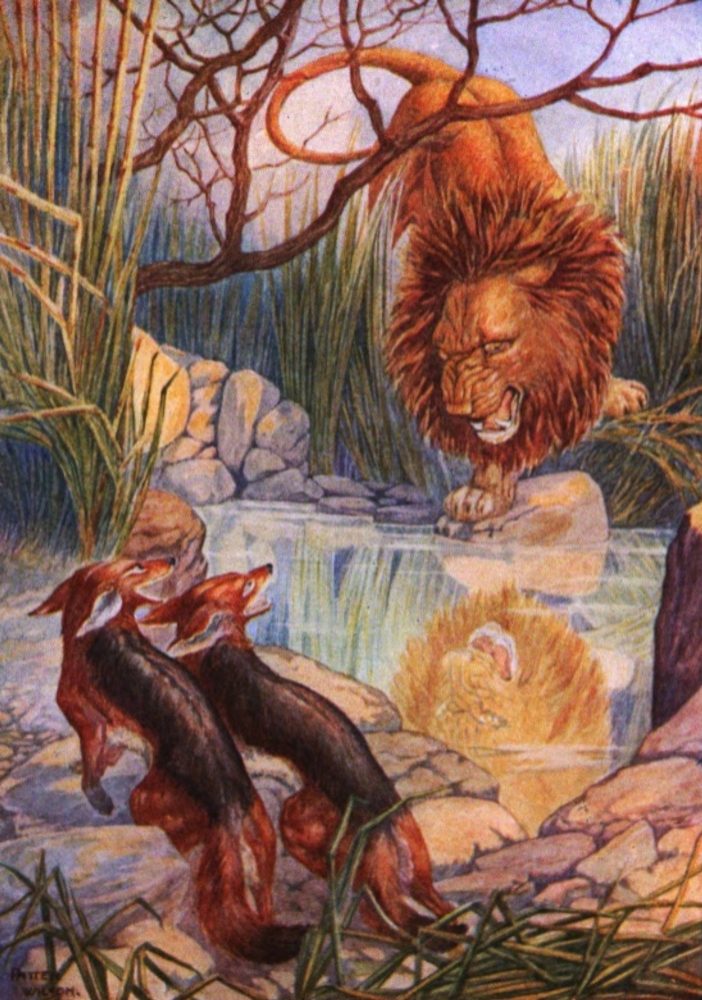

The Lion came close and looked

down into the water -- and a lion's face looked back at him out of the

water!

THE

LION IN THE WATER SHOOK HIS MANE AND SHOWED HIS TEETH

THE

LION IN THE WATER SHOOK HIS MANE AND SHOWED HIS TEETH

When he saw that, the Lion

roared and shook his mane and showed his teeth. And the lion in the

water shook

his mane and showed his teeth. The Lion above shook his mane again and

growled

again, and made a terrible face. But the lion in the water made just as

terrible a one, back. The Lion above couldn’t stand that. He leaped

down into

the well after the other lion.

But, of course, as you know

very well, there wasn’t any other lion! It was only the reflection in

the

water. So the poor old Lion floundered about and floundered about, and

as he

couldn't get up the steep sides of the well, he was drowned dead. And

when he

was drowned the little Jackals took hold of hands and danced round the

well,

and sang, --

"The Lion is dead! The

Lion is dead!

"We have killed the

great Lion who would have killed us!

"The Lion is dead! The

Lion is dead!

"Ao! Ao! Ao!"

LITTLE JACK

ROLLAROUND

Once upon a time there was a

wee little boy who slept in a tiny trundle-bed near his mother's great

bed. The

trundle-bed had castors on it so that it could be rolled about, and

there was

nothing in the world the little boy liked so much as to have it rolled.

When

his mother came to bed he would cry, "Roll me around! roll me

around!" And his mother would put out her hand from the big bed and

push

the little bed back and forth till she was tired. The little boy could

never

get enough; so for this he was called "Little Jack Rollaround."

One night he had made his

mother roll him about, till she fell asleep, and even then he kept

crying,

"Roll me around! roll me around!"' His mother pushed him about in her

sleep, until she fell too soundly aslumbering; then she stopped. But

Little

Jack Rollaround kept on crying, "Roll around! roll around!"

By and by the Moon peeped in

at the window. He saw a funny sight: Little Jack Rollaround was lying

in his

trundle-bed, and he had put up one little fat leg for a mast, and

fastened the

corner of his wee shirt to it for a sail; and he was blowing at it with

all his

might, and saying, "Roll around! roll around!"

Slowly, slowly, the little

trundle-bed boat began to move; it

sailed along the floor and up the wall and across the ceiling and down

again!

"More! more!"

cried Little Jack Rollaround; and the little boat sailed faster up the

wall,

across the ceiling, down the wall, and over the floor. The Moon

laughed at the

sight; but when Little Jack Rollaround saw the Moon, he called out,

"Open

the door, old Moon! I want to roll through the town, so that the people

can see

me!"

The Moon could not open the

door, but he shone in through the keyhole, in a broad band. And Little

Jack

Rollaround sailed his trundle-bed boat up the beam, through the

keyhole, and

into the street. "Make a light, old Moon," he said; "I want the

people to see me!"

So the good Moon made a

light and went along with him, and the little trundle-bed boat went

sailing

down the streets into the main street of the village. They rolled past

the town

hall and the schoolhouse and the church; but nobody saw Little Jack

Rollaround,

because everybody was in bed, asleep.

"Why don't the people

come to see me?" he shouted.

High up on the church

steeple, the Weather-vane answered, "It is no time for people to be in

the

streets; decent folk are in their beds."

"Then I'll go to the

woods, so that the animals may see me," said Little Jack. "Come

along, old Moon, and make a light!"

The good Moon went along and

made a light, and they came to the forest. "Roll! roll!" cried the

little boy; and the trundle-bed went trundling among the trees in the

great

wood, scaring up the chipmunks and startling the little leaves on the

trees.

The poor old Moon began to have a bad time of it, for the tree-trunks

got in

his way so that he could not go so fast as the bed, and every time he

got

behind, the little boy called, "Hurry up, old Moon, I want the beasts

to

see me!"

But all the animals were

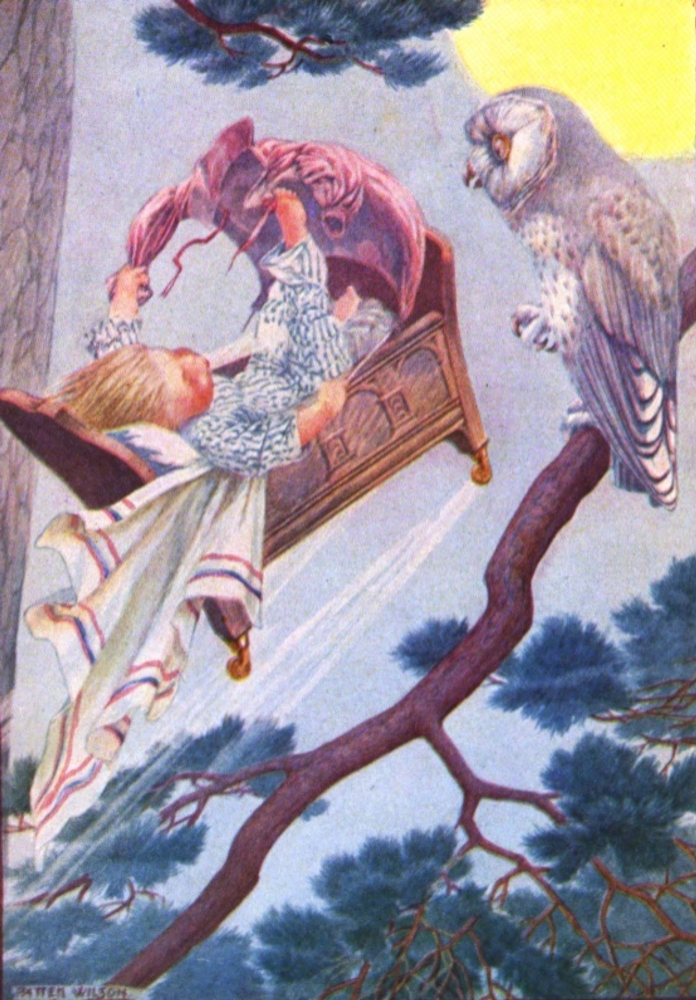

asleep, and nobody at all looked at Little Jack Rollaround except an

old White

Owl; and all she said was, "Who are you?"

ALL

SHE SAID WAS, 'WHO ARE YOU?'

ALL

SHE SAID WAS, 'WHO ARE YOU?'

The little boy did not like

her, so he blew harder, and the trundle-bed boat went sailing through

the

forest till it came to the end of the world.

"I must go home now; it

is late," said the Moon.

"I will go with you;

make a path! " said Little Jack Rollaround.

The kind Moon made a path up

to the sky, and up sailed the little bed into the midst of the sky. All

the

little bright Stars were there with their nice little lamps. And when

he saw

them, that naughty Little Jack Rollaround began to tease.

"Out of the way, there!

I am coming! " he shouted, and sailed the trundle-bed boat straight at

them. He bumped the little Stars right and left, all over the sky,

until every

one of them put his little lamp out and left it dark.

" Do not treat the

little Stars so," said the good Moon.

But Jack Rollaround only

behaved the worse: "Get out of the way, old Moon!" he shouted,

"I am coming!"

And he steered the little

trundle-bed straight into the old Moon's face, and bumped his nose!

This was too much for the

good Moon; he put out his big light, all at once, and left the sky

pitch-black.

"Make a light, old Moon! Make a light!" shouted the little boy. But

the Moon answered never a word, and Jack Rollaround could not see where

to

steer. He went rolling criss-cross, up and down, all over the sky,

knocking

into the planets and stumbling into the clouds, till he did not know

where he

was.

Suddenly he saw a big yellow

light at the very edge of the sky. He thought it was the Moon. "Look

out,

I am coming!" he cried, and steered for the light.

But it was not the kind old

Moon at all; it was the great mother Sun, just coming up out of her

home in the

sea, to begin her day's work.

"Aha, youngster, what

are you doing in my sky?" she said. And she picked Little Jack

Rollaround

up and threw him, trundle-bed boat and all, into the middle of the sea!

And I suppose he is there

yet, unless somebody picked him out again.

HOW BROTHER RABBIT FOOLED

THE WHALE AND THE ELEPHANT

One day little Brother

Rabbit was running along on the sand, lippety, lippety, when he saw the

Whale

and the Elephant talking together. Little Brother Rabbit crouched down

and

listened to what they were saying. This was what they were saying: --

"You are the biggest

thing on the land, Brother Elephant," said the Whale, "and I am the

biggest thing in the sea; if we join together we can rule all the

animals in

the world, and have our way about everything."

"Very good, very

good," trumpeted the Elephant; "that suits me; we will do it."

Little Brother Rabbit

snickered to himself. "They won't rule me," he said. He ran away and

got a very long, very strong rope, and he got his big drum, and hid the

drum a

long way off in the bushes. Then he went along the beach till he came

to the

Whale.

"Oh, please, dear,

strong Mr. Whale," he said, "will you have the great kindness to do

me a favour? My cow is stuck in the mud, a quarter of a mile from here.

And I

can't pull her out. But you are so strong and so obliging, that I

venture to

trust you will help me out."

The Whale was so pleased with

the compliment that he said, "Yes," at once.

"Then," said the

Rabbit, "I will tie this end of my long rope to you, and I will run

away

and tie the other end round my cow, and when I am ready I will beat my

big

drum. When you hear that, pull very, very hard, for the cow is stuck

very deep

in the mud."

"Huh! " grunted

the Whale, "I'll pull her out, if she is stuck to the horns."

Little Brother Rabbit tied

the rope-end to the Whale, and ran off, lippety, lippety, till he came

to the

place where the Elephant was.

"Oh, please, mighty and

kindly Elephant," he said, making a very low bow, "will you do me a

favor?"

"What is it? "

asked the Elephant.

"My cow is stuck in the mud, about a quarter of

a mile from here," said little Brother Rabbit, "and I cannot pull her

out. Of course you could. If you will be so very obliging as to help me

-"

"Certainly," said

the Elephant grandly, " certainly."

"Then," said

little Brother Rabbit, "I will tie one end of this long rope to your

trunk, and the other to my cow, and as soon as I have tied her tightly

I will

beat my big drum. When you hear

that, pull; pull as hard as you can, for my

cow is very heavy."

"Never fear," said

the Elephant, " I could pull twenty cows."

"I am sure you

could," said the Rabbit, politely, "only be sure to begin gently, and

pull harder and harder till you get her."

Then he tied the end of the

rope tightly round the Elephant's trunk, and ran away into the bushes.

There he

sat down and beat the big drum.

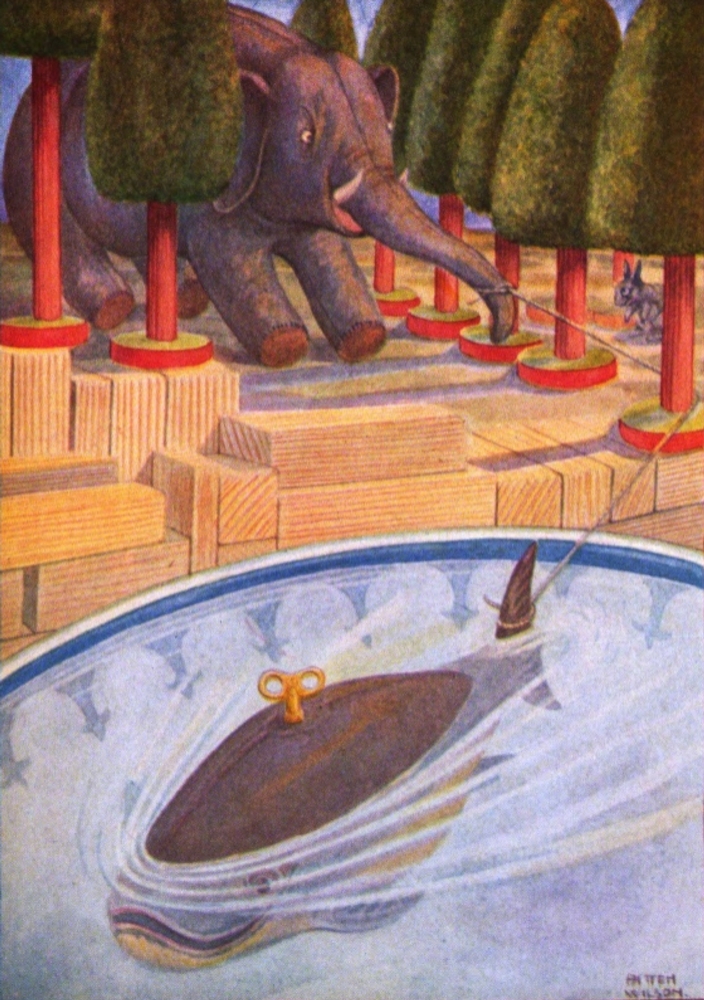

The Whale began to pull and

the Elephant began to pull, and in a jiffy the rope tightened till it

was

stretched as hard as could be.

"This is a remarkably

heavy cow," said the Elephant; "but I'll fetch her!" And he

braced his forefeet in the earth, and gave a tremendous pull.

"Dear me!" said

the Whale. "That cow must be stuck mighty tight;" and he drove his

tail deep in the water, and gave a marvelous pull.

He pulled harder; the

Elephant pulled harder. Pretty soon the Whale found himself sliding

toward the

land. The reason was, of course, that the Elephant had something solid

to

brace against, and, too, as fast as he pulled the rope in a little, he

took a

turn with it round his trunk!

But when the Whale found

himself sliding toward the land he was so provoked with the cow that he

dove

head first, down to the bottom of the sea. That was a pull! The

Elephant was

jerked off his feet, and came slipping and sliding to the beach, and

into the

surf. He was terribly angry. He braced himself with all his might, and

pulled

his best. At the jerk, up came the Whale out of the water.

"Who is pulling

me?" spouted the Whale.

"Who is pulling

me?" trumpeted the Elephant. And then each saw the rope in the other's

hold.

"I'll teach you to play

cow!" roared the Elephant.

"I'll show you how to

fool me!" fumed the Whale. And they began to pull again. But this time

the

rope broke, the Whale turned a somersault, and the Elephant fell over

backwards.

At that, they were both so

ashamed that neither would speak to the other. So that broke up the

bargain

between them.

And little Brother Rabbit

sat in the bushes and laughed, and laughed, and laughed.

THE

ELEPHANT . . . BRACED HIMSELF WITH ALL HIS MIGHT, AND PULLED HIS BEST

THE

ELEPHANT . . . BRACED HIMSELF WITH ALL HIS MIGHT, AND PULLED HIS BEST

THE LITTLE

HALF-CHICK

There was once upon a time a

Spanish Hen, who hatched out some nice little chickens. She was much

pleased

with their looks as they came from the shell. One, two, three, came out

plump

and fluffy; but when the fourth shell broke, out came a little

half-chick! It

had only one leg and one wing and one eye! It was just half a chicken.

The Hen-mother did not know

what in the world to do with the queer little Half-Chick. She was

afraid

something would happen to it, and she tried hard to protect it and keep

it from

harm. But as soon as it could walk the little Half-Chick showed a most

headstrong

spirit, worse than any of its brothers. It would not mind, and it would

go wherever

it wanted to; it walked with a funny little hoppity-kick,

hoppity-kick, and

got along pretty fast.

One day the little

Half-Chick said, "Mother, I am off to Madrid, to see the King!

Good-by."

The poor Hen-mother did

everything she could think of to keep

him from doing so foolish a thing, but the little Half-Chick laughed at

her

naughtily.

' "I'm for seeing the

King," he said; "this life is too quiet for me." And away he

went, hoppity-kick, hoppity-kick, over

the fields.

When he had gone some distance

the little Half-Chick came to a little brook that was caught in the

weeds and

in much trouble.

"Little

Half-Chick," whispered the Water, "I am so choked with these weeds

that I cannot move; I am almost lost, for want of room; please push the

sticks and

weeds away with your bill and help me."

"The idea!" said

the little Half-Chick. "I cannot be bothered with you; I am off for

Madrid, to see the King!" And in spite of the brook's begging he went

away, hoppity-kick, hoppity-kick.

A bit farther on, the Half-Chick

came to a Fire, which was smothered in

damp sticks and in great distress.

"Oh, little

Half-Chick," said the Fire, "you are just in time to save me. I am

almost dead for want of air. Fan me a little with your wing, I beg."

"The idea!" said

the little Half-Chick. "I cannot be bothered with you; I am off to

Madrid,

to see the King!" And he went laughing off, hoppity-kick, hoppity-kick.

When he had hoppity-kicked a

good way, and was near Madrid, he came to a clump of bushes, where the

Wind was

caught fast. The Wind was whimpering, and begging to be set free.

"Little

Half-Chick," said the Wind, "you are just in time to help me; if you

will brush aside these twigs and leaves, I can get my breath; help me,

quickly!

"

"Ho! the idea!"

said the little Half-Chick. "I have no time to bother with you. I am

going

to Madrid to see the King." And he went off, hoppity-kick,

hoppity-kick,

leaving the Wind to smother.

After a while he came to

Madrid and to the palace of the King. Hoppity-kick, hoppity-kick, the

little

Half-Chick skipped past the sentry at the gate, and hoppity-kick,

hoppity-kick,

he crossed the court. But as he was passing the windows of the kitchen

the Cook

looked out and saw him.

"The very thing for the

King's dinner!" she said. "I was needing a chicken!" And she

seized the little Half-Chick by his one wing and threw him into a

kettle of

water on the fire.

The Water came over the

little Half-Chick's feathers, over his head, into his eye. It was

terribly uncomfortable.

The little Half-Chick cried out, --

"Water, don't drown me!

Stay down, don't come so high!"

But the Water said,

"Little Half-Chick, little Half-Chick, when I was in trouble you would

not help me," and came higher than ever.

Now the Water grew warm,

hot, hotter, frightfully hot; the little Half-Chick cried out, "Do not

burn so hot, Fire! You are burning me to death! Stop! "

But the Fire said,

"Little Half-Chick, little Half-Chick, when I was in trouble you would

not help me," and burned hotter than ever.

Just as the little Half-Chick

thought he must suffocate, the Cook took the cover off, to look at the

dinner.

"Dear me," she said, "this chicken is no good; it is burned to a

cinder." And she picked the little Half-Chick up by one leg and threw

him

out of the window.

In the air he was caught by

a breeze and taken up higher than the trees. Round and round he was

twirled

till he was so dizzy he thought he must perish. "Don't blow me so,

Wind," he cried, "let me down!"

"Little Half-Chick,

little Half-Chick," said the Wind, " when I was in trouble you would

not help me!" And the Wind blew him straight up to the top of the

church

steeple, and stuck him there, fast!

There he stands to this day,

with his one eye, his

one wing, and his one leg.

He cannot hoppity-kick any more, but he turns slowly round when the

wind blows,

and keeps his head toward it, to hear what it says.

|