| XV. The Solution

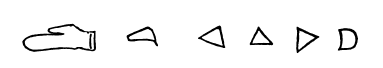

IF you can understand that all the extraordinary events of the previous chapters occurred without the knowledge of Fleet Street, that eminent journalists went about their business day by day without being any the wiser, that eager news editors were diligently searching the files of the provincial press for news items, with the mystery of the safe at their very door, and that reporters all over London were wasting their time over wretched little motor-bus accidents and gas explosions, you will all the easier appreciate the journalistic explosion that followed the double inquest on Spedding and his victim. It is outside the province of this story to instruct the reader in what is so much technical detail, but it may be said in passing that no less than twelve reporters, three sub-editors, two "crime experts," and one publisher were summarily and incontinently discharged from their various newspapers in connection with the "Safe Story." The Megaphone alone lost five men, but then the Megaphone invariably discharges more than any other paper, because it has got a reputation to sustain. Flaring contents bills, heavy black headlines, and column upon column of solid type, told the story of Reale's millions, and the villainous lawyer, and the remarkable verse, and the "Borough Lot". There were portraits of Angel and portraits of Jimmy and portraits of Kathleen (sketched in court and accordingly repulsive), and plans of the lawyer's house at Clapham and sketches of the Safe Deposit. So for the three days that the coroner's inquiry lasted London, and Fleet Street more especially, revelled in the story of the old croupier's remarkable will and its tragic consequences. The Crown solicitors very tactfully skimmed over Jimmy's adventurous past, were brief in their examination of Kathleen; but Angel's interrogation lasted the greater part of five hours, for upon him devolved the task of telling the story in full. It must be confessed that Angel's evidence was a remarkably successful effort to justify all that Scotland Yard had done. There were certain irregularities to be glossed over, topics to be avoided why, for instance, official action was not taken when it was seen that Spedding contemplated a felony. Most worthily did Angel hold the fort for officialdom that day, and when he vacated the box he left behind him the impression that Scotland Yard was all foreseeing, all wise, and had added yet another to its list of successful cases. The newspaper excitement lasted exactly four days. On the fourth day, speaking at the Annual Congress of the British Association, Sir William Farran, that great physician, in the course of an illuminating address on "The first causes of disease," announced as his firm conviction that all the ills that flesh is heir to arise primarily from the wearing of boots, and the excitement that followed the appearance in Cheapside of a converted Lord Mayor with bare feet will long be remembered in the history of British journalism. It was enough, at any rate, to blot out the memory of the Reale case, for immediately following the vision of a stout and respected member of the Haberdasher Company in full robes and chain of office entering the Mansion House insufficiently clad there arose that memorable newspaper discussion "Boots and Crime," which threatened at one time to shake established society to its very foundations. "Bill's a brick," wrote Angel to Jimmy. "I suggested to him that he might make a sensational statement about microbes, but he said that the Lancet had worked bugs to death, and offered the 'no boots' alternative." It was a fortnight after the inquiry that Jimmy drove to Streatham to carry out his promise to explain to Kathleen the solution of the cryptogram. It was his last visit to her, that much he had decided. His rejection of her offer to equally share old Reale's fortune left but one course open to him, and that he elected to take. She expected him, and he found her sitting before a cosy fire idly turning the leaves of a book. Jimmy stood for a moment in an embarrassed silence. It was the first time he had been alone with her, save the night he drove with her to Streatham, and he was a little at a loss for an opening. He began conventionally enough speaking about the weather, and not to be outdone in commonplace, she ordered tea. "And now, Miss Kent," he said, "I have got to explain to you the solution of old Reale's cryptogram." He took a sheet of paper from his pocket covered with hieroglyphics. "Where old Reale got his idea of the cryptogram from was, of course, Egypt. He lived there long enough to be fairly well acquainted with the picture letters that abound in that country, and we were fools not to jump at the solution at first. I don't mean you," he added hastily. "I mean Angel and I and Connor, and all the people who were associated with him." The girl was looking at the sheet, and smiled quietly at the faux pas. "How he came into touch with the 'professor !" "What has happened to that poor old man?" she asked. "Angel has got him into some kind of institute," replied Jimmy. "He's a fairly common type of cranky old gentleman. 'A science potterer,' Angel calls him, and that is about the description. He's the sort of man that haunts the Admiralty with plans for unsinkable battleships, a 'minus genius' that's Angel's description too who, with an academic knowledge and a good memory, produced a reasonably clever little book, that five hundred other schoolmasters might just as easily have written. How the professor came into Reale's life we shall never know. Probably he came across the book and discovered the author, and trusting to his madness, made a confidant of him. Do you remember," Jimmy went on, "that you said the figures reminded you of the Bible? Well, you are right. Almost every teacher's Bible, I find, has a plate showing how the alphabet came into existence." He indicated with his finger as he spoke. "Here is the Egyptian hieroglyphic. Here is a 'hand' that means 'D,' and here is the queer little Hieratic wiggle that means the same thing, and you see how the Phoenician letter is very little different to the hieroglyphic, and the Greek 'delta' has become a triangle, and locally it has become the 'D' we know." He sketched rapidly.  "All this is horribly learned," he said, "and has got nothing to do with the solution. But old Reale went through the strange birds, beasts and things till he found six letters, S P R I N G, which were to form the word that would open the safe." "It is very interesting," she said, a little bewildered. "The night you were taken away," said Jimmy, "we found the word and cleared out the safe in case of accidents. It was a very risky proceeding on our part, because we had no authority from you to act on your behalf." "You did right," she said. She felt it was a feeble rejoinder, but she could think of nothing better. "And that is all," he ended abruptly, and looked at the clock. "You must have some tea before you go," she said hurriedly. They heard the weird shriek of a motor-horn outside, and Jimmy smiled. "That is Angel's newest discovery," he said, not knowing whether to bless or curse his energetic friend for spoiling the tκte-ΰ-tκte. "Oh!" said the girl, a little blankly he thought. "Angel is always experimenting with new noises," said Jimmy, "and some fellow has introduced him to a motor-siren which is claimed to possess an almost human voice." The bell tinkled, and a few seconds after Angel was ushered into the room. "I have only come for a few minutes," he said cheerfully. "I wanted to see Jimmy before he sailed, and as I have been called out of town unexpectedly " "Before he sails?" she repeated slowly. "Are you going away?" "Oh, yes, he's going away," said Angel, avoiding Jimmy's scowling eyes. "I thought he would have told you." "I " began Jimmy. "He's going into the French Congo to shoot elephants," Angel rattled on; "though what the poor elephants have done to him I have yet to discover." "But this is sudden?" She was busy with the tea things, and had her back toward them, so Jimmy did not see her hand tremble. "You're spilling the milk," said the interfering Angel. "Shall I help you?" "No, thank you," she replied tartly. "This tea is delicious," said Angel, unabashed, as he took his cup. He had come to perform a duty, and he was going through with it. "You won't get afternoon tea on the Sangar River, Jimmy. I know because I have been there, and I wouldn't go again, not even if they made me governor of the province." "Why?" she asked, with a futile attempt to appear indifferent. "Please take no notice of Angel, Miss Kent," implored Jimmy, and added malevolently, "Angel is a big game shot, you know, and he is anxious to impress you with the extent and dangers of his travels." "That is so," agreed Angel contentedly, "but all the same, Miss Kent, I must stand by what I said in regard to the 'Frongo.' It's a deadly country, full of fever. I've known chaps to complain of a headache at four o'clock and be dead by ten, and Jimmy knows it too." "You are very depressing today, Mr. Angel," said the girl. She felt unaccountably shaky, and tried to tell herself that it was because she had not recovered from the effects of her recent exciting experiences. "I was with a party once on the Sangar River," Angel said, cocking a reflective eye at the ceiling. "We were looking for elephants, too, a terribly dangerous business. I've known a bull elephant charge a hunter and " "Angel!" stormed Jimmy, "will you be kind enough to reserve your reminiscences for another occasion?" Angel rose and put down his teacup sadly. "Ah, well!" he sighed lugubriously, "after all, life is a burden, and one might as well die in the French Congo a particularly lonely place to die in, I admit as anywhere else. Goodbye, Jimmy!" He held out his hand mournfully. "Don't be a goat!" entreated Jimmy. "I will let you know from time to time how I am; you can send your letters via Sierra Leone." "The White Man's Grave!" murmured Angel audibly. "And I'll let you know in plenty of time when I return." "When!" said Angel significantly. He shook hands limply, and with the air of a man taking an eternal farewell. Then he left the room, and they could hear the eerie whine of his patent siren growing fainter and fainter. "Confound that chap!" said Jimmy. "With his glum face and extravagant gloom he " "Why did you not tell me you were going?" she asked him quietly. She stood with a neat foot on the fender and her head a little bent. "I had come to tell you," said Jimmy. "Why are you going?" Jimmy cleared his throat. "Because I need the change," he said almost brusquely. "Are you tired of your friends?" she asked, not lifting her eyes. "I have so few friends," said Jimmy bitterly. "People here who are worth knowing know me." "What do they know?" she asked, and looked at him. "They know my life," he said doggedly, "from the day I was sent down from Oxford to the day I succeeded to my uncle's title and estates. They know I have been all over the world picking up strange acquaintances. They know I was one of the" he hesitated for a word "gang that robbed Rahbat Pasha's bank; that I held a big share in Reale's ventures a share he robbed me of, but let that pass; that my life has been consistently employed in evading the law." "For whose benefit?" she asked. "God knows," he said wearily, "not for mine. I have never felt the need of money, my uncle saw to that. I should never have seen Reale again but for a desire to get justice. If you think I have robbed for gain, you are mistaken. I have robbed for the game's sake, for the excitement of it, for the constant fight of wits against men as keen as myself. Men like Angel made me a thief." "And now ?" she asked. "And now," he said, straightening himself up, "I am done with the old life. I am sick and sorry and finished." "And is this African trip part of your scheme of penitence?" she asked. "Or are you going away because you want to forget " Her voice had sunk almost to a whisper, and her eyes were looking into the fire. "What?" he asked huskily. "To forget me," she breathed. "Yes, yes," he said, "that is what I want to forget." "Why?" she said, not looking at him. "Because oh, because I love you too much, dear, to want to drag you down to my level. I love you more than I thought it possible to love a woman so much, that I am happy to sacrifice the dearest wish of my heart, because I think I will serve you better by leaving you." He took her hand and held it between his two strong hands. "Don't you think," she whispered, so that he had to bend closer to hear what she said, "don't you think I I ought to be consulted?" "You you," he cried in wonderment, "would you " She looked at him with a smile, and her eyes were radiant with unspoken happiness. "I want you, Jimmy," she said. It was the first time she had called him by name. "I want you, dear." His arms were about her, and her lips met his. They did not hear the tinkle of the bell, but they heard the knock at the door, and the girl slipped from his arms and was collecting the tea-things when Angel walked in. He looked at Jimmy inanely, fiddling with his watch chain, and he looked at the girl. "Awfully sorry to intrude again," he said, "but I got a wire at the little post-office up the road telling me I needn't take the case at Newcastle, so I thought I'd come back and tell you, Jimmy, that I will take what I might call a 'cemetery drink' with you tonight." "I am not going," said Jimmy, recovering his calm. "Not not going?" said the astonished Angel. "No," said the girl, speaking over his shoulder, "I have persuaded him to stay." "Ah, so I see!" said Angel, stooping to pick up two hairpins that lay on the hearthrug.

|

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2018

(Return to Web Text-ures)