| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Ancient Tales and Folk-Lore of Japan Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| THE BLIND BEAUTY NEARLY

three hundred years ago (or, according to my story-teller, in the

second year

of Kwanei, which would be 1626, the period of Kwanei having begun in

1624 and

ended in 1644) there lived at Maidzuru, in the province of Tango, a

youth named

Kichijiro. Kichijiro

had been born at the village of Tai, where his father had been a

native; but on

the death of the father he had come with his elder brother, Kichisuke,

to

Maidzuru. The brother was his only living relation except an uncle, and

had

taken care of him for four years, educating him from the age of eleven

until

fifteen; and Kichijiro was very grateful, and determined that now he

had

reached the age of fifteen he must no longer be a drag on his brother,

but must

begin to make a way in the world for himself. After

looking about for some weeks, Kichijiro found employment with Shiwoya

Hachiyemon, a merchant in Maidzuru. He worked very hard, and soon

gained his

master's friendship; indeed, Hachiyemon thought very highly of his

apprentice;

he favoured him in many ways over older clerks, and finally entrusted

him with

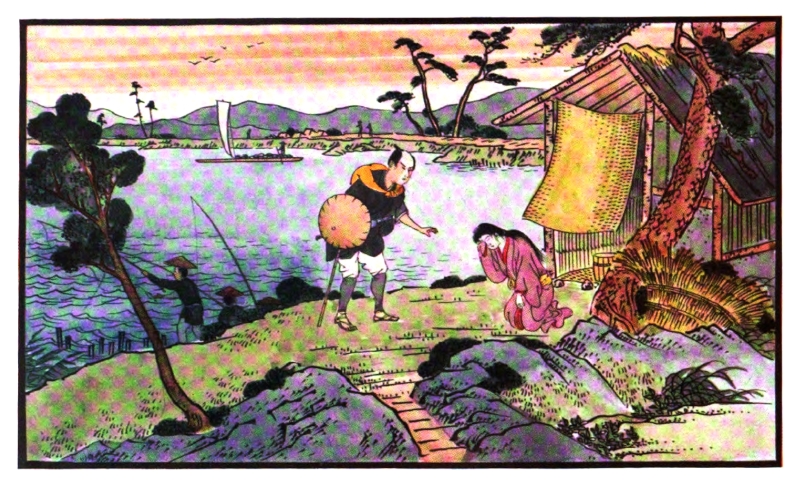

the key of his safes, which contained documents and much money. Now, Hachiyemon had a daughter of Kichijiro's age, of great beauty and promise, and she fell desperately in love with Kichijiro, who himself was at first unaware of this. The girl's name was Ima, O Ima San, and she was one of those delightful ruddy, happy-faced girls whom only Japan can produce — a mixture of yellow and red, with hair and eyebrows as black as a raven. Ima paid Kichijiro compliments now and then; but he was a boy who thought little of love. He intended to get on in the world, and marriage was a thing which had not yet entered into his mind.  Kichijiro Finds Poor O Ima Blind After

Kichijiro had been some six months in the employment of Hachiyemon he

stood

higher than ever in the master's estimation; but the other clerks did

not like

him. They were jealous. One was specially so. This was Kanshichi, who

hated him

not only because he was favoured by the merchant but also because he

himself

loved O Ima, who had given him many a rebuff when he had attempted to

make love

to her. So great did this secret hate become, at last Kanshichi vowed

that he

would be revenged upon Kichijiro, and if necessary upon his master

Hachiyemon

and his daughter O Ima as well; for he was a wicked and scheming man. One

day an opportunity occurred. Kichijiro

had so far secured confidence that the master had sent him off to

Kasumi, in

Tajima Province, there to negotiate the purchase of a junk. While he

was away

Kanshichi broke into the room where the safe was kept, and took

therefrom two

bags containing money in gold up to the value of 200 ryo. He effaced

all signs

of his action, and went quietly back to his work. Two or three days

later

Kichijiro returned, having successfully accomplished his mission, and,

after

reporting this to the master, set to his routine work again. On

examining the

safe, he found that the 200 ryo of gold were missing, and, he having

reported

this, the office and the household were thrown into a state of

excitement. After

some hours of hunting for the money it was found in a koro

(incense-burner)

which belonged to Kichijiro, and no one was more surprised than he. It

was

Kanshichi who had found it, naturally, after having put it there

himself; he

did not accuse Kichijiro of having stolen the money — his plans were

more

deeply laid. The money having been found there, he knew that Kichijiro

himself

would have to say something. Of course Kichijiro said he was absolutely

innocent, and that when he had left for Kasumi the money was safe — he

had seen

it just before leaving. Hachiyemon

was sorely distressed. He believed in the innocence of Kichijiro; but

how was

he to prove it? Seeing that his master did not believe Kichijiro

guilty,

Kanshichi decided that he must do something which would render it more

or less

impossible for Hachiyemon to do otherwise than to send his hated rival

Kichijiro away. He went to the master and said: 'Sir,

I, as your head clerk, must tell you that, though perhaps Kichijiro is

innocent, things seem to prove that he is not, for how could the money

have got

into his koro? If he is not punished, the theft will reflect on all of

us

clerks, your faithful servants, and I myself should have to leave your

service,

for all the others would do so, and you would be unable to carry on

your

business. Therefore I venture to tell you, sir, that it would be

advisable in

your own interests to send poor Kichijiro, for whose misfortune I

deeply

grieve, away.' Hachiyemon

saw the force of this argument, and agreed. He sent for Kichijiro, to

whom he

said: 'Kichijiro,

deeply as I regret it, I am obliged to send you away. I do not believe

in your

guilt, but I know that if I do not send you away all my clerks will

leave me,

and I shall be ruined. To show you that I believe in your innocence, I

will

tell you that my daughter Ima loves you, and that if you are willing,

and after

you can prove your innocence, nothing would give me greater pleasure

than to

have you back as my son-in — law. Go now. Try and think how you can

prove your

innocence. My best wishes go with you.' Kichijiro

was very sad. Now that he had to go, he found that he should more than

miss the

companionship of the sweet O Ima. With tears in his eyes, he vowed to

the

father that he would come back, prove his innocence, and marry O Ima;

and with

O Ima herself he had his first love scene. They vowed that neither

should rest

until the scheming thief had been discovered, and they were both

reunited in

such a way that nothing could part them. Kichijiro

went back to his brother Kichisuke at Tai village, to consult as to

what it

would be best for him to do to re-establish his reputation. After a few

weeks,

he was employed through his brother's interest and that of his only

surviving

uncle in Kyoto. There he worked hard and faithfully for four long

years,

bringing much credit to his firm, and earning much admiration from his

uncle,

who made him heir to considerable landed property, and gave him a share

in his

own business. Kichijiro found himself at the age of twenty quite a rich

man. In

the meantime calamity had come on pretty O Ima. After Kichijiro had

left

Maidzuru, Kanshichi began to pester her with attentions. She would have

none of

him; she would not even speak to him; and so exasperated did he become

at last

that he used to waylay her. On one occasion he resorted to violence and

tried

to carry her away by force. Of this she complained to her father, who

promptly

dismissed him from his service. This

made villain Kanshichi angrier than ever. As the Japanese proverb says,

'Kawaisa amatte nikusa ga hyakubai,' — which means, 'Excessive love is

hatred.'

So it was with Kanshichi: his love turned to hatred. He thought of how

he could

be avenged on Hachiyemon and O Ima. The most simple means, he thought,

would be

to burn down their house, the business offices, and the stores of

merchandise:

that must bring ruin. So one night Kanshichi set about doing these

things and

accomplished them most successfully — with the exception that he

himself was

caught in the act and sentenced to a heavy punishment. That was the

only

satisfaction which was got by Hachiyemon, who was all but ruined; he

sent away

all his clerks and retired from business, for he was too old to begin

again. With

just enough to keep life and body together, Hachiyemon and his pretty

daughter

lived in a little cheap cottage on the banks of the river, where it was

Hachiyemon's only pleasure to fish for carp and jakko. For three years

he did

this, and then fell ill and died. Poor O Ima was left to herself, as

lovely as

ever, but mournful. The few friends she had tried to prevail on her to

marry

somebody — anybody, they said, sooner than live alone, — but to this

advice the

girl would not listen. 'It is better to live miserably alone,' she

said, 'than

to marry one for whom you do not care; I can love none but Kichijiro,

though I

shall not see him again.' O Ima

spoke the truth on that occasion, without knowing it, for, true as it

is that

it never rains but it pours, O Ima was to have more trouble. An eye

sickness

came to her, and in less than two months after her father's death the

poor girl

was blind, with no one to attend to her wants but an old nurse who had

stuck to

her through all her troubles. Ima had barely sufficient money to pay

for rice. It

was just at this time that Kichijiro's success was assured: his uncle

had given

him a half interest in the business and made a will in which he left

him his

whole property. Kichijiro decided to go and report himself to his old

master at

Maidzuru and to claim the hand of O Ima his daughter. Having learned

the sad

story of downfall and ruin, and also of Ima's blindness, Kichijiro went

to the

girl's cottage. Poor O Ima came out and flung herself into his arms,

weeping

bitterly, and crying: 'Kichijiro, my beloved! this is indeed almost the

hardest

blow of all. The loss of my sight was as nothing before; but now that

you have

come back, I cannot see you, and how I long to do so you can but little

imagine! It is indeed the saddest blow of all. You cannot now marry

me.' Kichijiro

petted her, and said, 'Dearest Ima, you must not be too hasty in your

thoughts.

I have never ceased thinking of you; indeed, I have grown to love you

desperately. I have property now in Kyoto; but should you prefer to do

so, we

will live here in this cottage. I am ready to do anything you wish. It

is my

desire to re-establish your father's old business, for the good of your

family;

but first and before even this we will be married and never part again.

We will

do that tomorrow. Then we will go together to Kyoto and see my uncle,

and ask

for his advice. He is always good and kind, and you will like him — he

is sure

to like you.' Next

day they started on their journey to Kyoto, and Kichijiro saw his

brother and

his uncle, neither of whom had any objection to Kichijiro's bride on

account of

her blindness. Indeed, the uncle was so much pleased at his nephew's

fidelity

that he gave him half of his capital there and then. Kichijiro built a

new

house and offices in Maidzuru, just where his first master Hachiyemon's

place

had been. He re-established the business completely, calling his firm

the

Second Shiwoya Hachiyemon, as is often done in Japan (which adds much

to the

confusion of Europeans who study Japanese Art, for pupils often take

the names

of their clever masters, calling themselves the Second, or even the

Third or

the Fourth). In

the garden of their Maidzuru house was an artificial mountain, and on

this

Kichijiro had erected a tombstone or memorial dedicated to Hachiyemon,

his

father-in-law. At the foot of the mountain he erected a memorial to

Kanshichi.

Thus he rewarded the evil wickedness of Kanshichi by kindness, but

showed at

the same time that evil-doers cannot expect high places. It is to be

hoped that

the spirits of the two dead men became reconciled. They say in Maidzuru that the memorial tombs still stand. |