| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Ancient Tales and Folk-Lore of Japan Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| A STORMY NIGHT'S TRAGEDY1 ALL

who have read anything of Japanese history must have heard of Saigo

Takamori,

who lived between the years 1827 and 1877. He was a great Imperialist,

fighting

for the Emperor until 1876, when he gave over owing to his disapproval

of the

Europeanisation going on in the country and the abandonment of ancient

national

ways. As practical Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Army, Saigo fled

to

Kagoshima, where he raised a body of faithful followers, which was the

beginning of the Satsuma Rebellion. The Imperialists defeated them, and

in

September of 1877 Saigo was killed — some say in the last battle, and

others

that he did 'seppuku,' and that his head was cut off and secretly

buried, so

that it should not fall into the hands of his enemies. Saigo Takamori

was

highly honoured even by the Imperialists. It is hard to call him a

rebel. He

did not rebel against his Emperor, but only against the revolting idea

of

becoming Europeanised. Who can say that he was not right? He was a man

of fine

sentiment and great loyalty. Should all of us follow meekly the

Imperial order

in England if we were told that we were to practise the manners and

customs of

South Sea Islanders? That would be hardly less revolting to us than

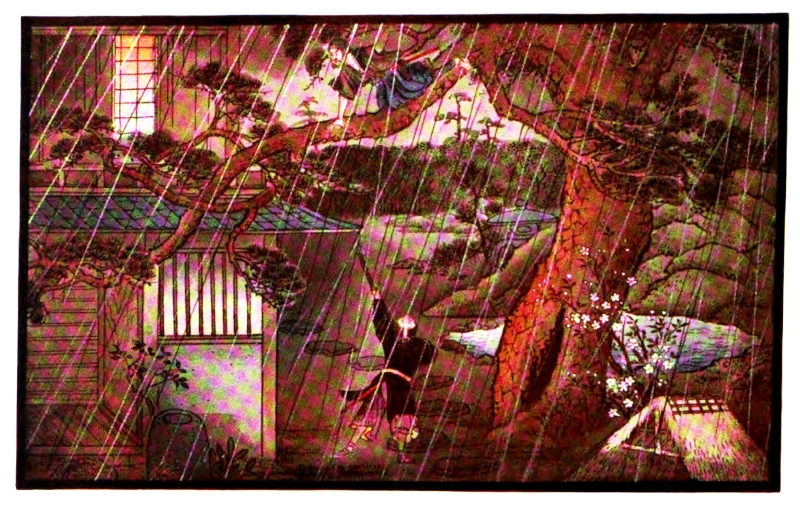

Europeanisation was to Saigo. In the first year of Meiji 1868 the Tokugawa army had been badly beaten by Saigo at Fushimi, and Field-Marshal Tokugawa Keiki had the greatest difficulty in getting down to the sea and escaping to Yedo. The Imperial army proceeded along the Tokaido road, determined to break up the Tokugawa force. Their advance guard had reached Hiratsuka, under Mount Fuji, on the coast.  The Sentry Finds Watanabe Tatsuzo on the Pine Branch It

was a spring day, the 5th of April, and the cherry trees were in full

bloom.

The country folk had come in to see the victorious troops, who formed

the

advance guard of those who had beaten the Tokugawa. There were many

beggars

about, together with pedlars and sellers of sweets, roasted potatoes,

and

what-not. Towards evening clouds carne over the skies; at five o'clock

rain

began; at six every one was under cover. At

the principal inn were a party of the Headquarters’ Staff officers,

including

the gallant Saigo. They were making the best of the bad weather, and

not

feeling particularly lively, when they heard the soft and melodious

notes of

the shakuhachi at the gate. 'That

is the poor blind beggar we saw playing near the temple to-day,' said

one.

'Yes: so it is,' said another. 'The poor fellow must be very wet and

miserable.

Let us call him in.' 'A

capital idea,' assented all of them, among whom was Saigo Takamori. 'We

will

have him in and raise a subscription for him if he can raise our

spirits in

this weather.' They gave the landlord an order to admit the blind

flute-player.

The

poor man was led in by a side door and brought into the presence of the

officers. 'Gentlemen,' said he, you have done me a very great honour,

and a

kindness, for it is not pleasant to stand outside playing in the rain

with

cotton clothes on. I think I can repay you, for I am said to play the

shakuhachi well. Since I have been blind it has become my only

pleasure, and

not only that but also my only means of living. It is hard now in these

unsettled

days, when everything is upside-down, to earn a living. Not many

travellers

come to the inns while the Imperial troops occupy them. These are hard

days,

gentlemen.' 'They

may be hard days for you, poor blind fellow; but say nothing against

the Imperial

troops, for we have to be suspicious, there being spies of the

Tokugawa. Three

eyes, indeed, does each of us need in his head.' 'Well,

well, I have no wish to say aught against the Imperial troops,' said

the blind

man. 'All I have to say is that it is precious hard for a blind man to

earn

enough rice wherewith to fill his stomach. Only once a-week on an

average am I

called to play to private parties or to shampoo some rheumatic person

such as

this wet weather produces — the blessing of the Gods be on it!' 'Well,

we will see what we can do for you, poor fellow,' said Saigo. 'Go round

the

room, and see what you can collect, and then we will start the

concert.' Matsuichi

did as he was bid, and returned to Saigo some ten minutes later with

five or

six yen, to which Saigo added, saying: 'There,

poor fellow: what do you think of that? Say no more that the Imperial

troops

cause you to have an empty belly. Say, rather, that if you lived near

them long

the skin of your belly might become so overstretched as to cause you

perforce

to open your eyes, and then indeed you might find yourself put about

for a

trade. But let us hear your music. We are dull of spirit to-night, and

want

enlivening.' 'Oh,

gentlemen, this is too much, far too much, for my poor music! Take some

of it

back.' 'No,

no,' they answered. 'We are troops and officers of the Imperial Army:

our lives

are uncertain from day to day. It is a pleasure to give, and to enjoy

music

when we can.' The

blind man began to play, and he played long and late. Sometimes his

airs were

lively, and at other times as mournful as the spring wind which blew

through

the cherry trees; but his manner was enchanting, and all were grateful

to him

for having afforded a night's amusement. At eleven o'clock the concert

finished

and they went to rest; the blind beggar left the inn; and Kato

Shichibei, the

proprietor, locked it up, in spite of the sentries posted outside. The

inn was surrounded by hedges, and several clumps of bamboos stood in

the

corners. At the far end was an artificial mountain with a lake at its

foot, and

near the lake a little summer-house over which towered a huge and

ancient pine

tree, one of the branches of which stretched right back over the roof

of the

inn. At about one o'clock in the morning the form of a man might have

been seen

stealthily climbing this huge tree until he had reached the branch

which hung

over the inn. There he stretched himself flat, and began squirming

along,

evidently intent upon reaching the upper floor of the house.

Unfortunately for

himself, he cracked a small branch of dead wood, and the sound caused a

sentry

to look up. 'Who goes there?' cried he, bringing his musket round; but

there

was no answer. The sentry shouted for help, and it was not more than

twenty

seconds before the whole house was up and out. No escape for the man on

the

tree was possible. He was taken prisoner. Imagine the astonishment of

all when

they found that he was the blind beggar, but now not blind at all; his

eyes

flashed fire of indignation at his captors, for the great plan of his

young life

was dead. 'Who

is he?' cried one and all, 'and why the trickery of being blind last

evening?' 'A

spy — that is what he is! A Tokugawa spy,' said one. 'Take him to

Headquarters,

so that the chief officers may interrogate him; and be careful to hold

his hands,

for he has every appearance of being a samurai and a fighter.' And

so the prisoner was led off to the Temple of Hommonji, where the

Headquarters

of the Staff temporarily were. The

prisoner was brought into the presence of Saigo Takamori and four other

Imperial officers, one of whom was Katsura Kogoro. He was made to

kneel. Then

Saigo, who was the Chief, said, 'Hold your head up and give us your

name.' The

prisoner answered: 'I am

Watanabe Tatsuzo. I am one of those who have the honour of belonging to

the

bodyguard of the Tokugawa Government.' 'You

are bold,' said Saigo. 'Will you have the goodness to tell us why you

have been

masquerading as a blind beggar, and why you were caught in an attempt

to break

into the inn?' 'I

found that the Imperial Ambassador was sleeping there, and our cause is

not

bettered by killing ordinary officers!' 'You

are a fool,' answered Saigo. 'How much better would you find yourself

off if

you killed Yanagiwara, Hashimoto, or Katsura?' 'Your

question is stupid,' was the unabashed answer. 'Every man of us does

his

little. My efforts are only a fragment; but little by little we shall

gain our

ends.' 'Have

you a comrade here?' asked Saigo. 'Oh,

no,' answered the prisoner. 'We act individually as we think best for

the cause.

It was my intention to kill any one of importance whose death might

strengthen

us. I was acting entirely as I thought best.' And

Saigo said: 'Your

loyalty does you credit, and I admire you for that; but you should

recognise

that after the last victory of the Imperial troops at Fushimi the

Tokugawa's

tenure of office, extending over three hundred years, has come to an

end. It is

only natural that the Imperial family should return to power. Your

intention is

presumably to support a power that is finished. Have you never heard

the

proverb which says that "No single support can hold a falling tower"?

Now tell me truthfully the absurd ideas which appear to exist in your

mind. Do

you really think that the Tokugawa have any further chance?' 'If

you were any other than the heroic or admirable Saigo I should refuse

to answer

these questions,' said the prisoner; 'but, as you are the great Saigo

Takamori

and I admire your loyalty and courage, I will confess that after our

defeat

some two hundred of us samurai formed into a society swearing to

sacrifice our

lives to the cause in any way that we were able. I regret to say that

nearly

all ran away, and that I am (as far as I am able to judge) about the

only one

left. As you will execute me, there will be none.' 'Stop,'

cried Saigo: 'say no more. Let me ask you: Will you not join us? Look

upon the

Tokugawa as dead. Too many faithful but ignorant samurai have died for

them.

The Imperial family must reign: nine-tenths of the country demand it.

Though

your guilt stands confessed, your loyalty is admirable, and we should

gladly

take you to our side. Think before you answer.' No

thought was necessary. Watanabe Tatsuzo answered instantly. 'No —

never. Though alone, I will not be unfaithful to my cause. You had

better behead

me before the day dawns. I see the strength of your arguments that the

Imperial

family must and should reign; but that cannot alter my decision with

regard to

my own fate; Saigo

stood up and said: 'Here

is a man whom we must respect. There are many Tokugawa who have joined

our

cause through fear; but they retain hate in their hearts. Look, all of

you, at

this Watanabe, and forget him not, for he is a noble man and true to

the

death.' So saying, Saigo bowed to Watanabe, and then, turning to the

guard,

said: 'Take

the prisoner to the Sambon matsu,2 and behead him as soon as

the day

dawns.' Watanabe

Tatsuzo was led forth and executed accordingly. There

is a cross-road on the way leading to Mariko, to the right of the Nitta

Ferry,

some five or six cho from the hill where is the Hommonji Temple,

Ikegami, in

Ebaragun, Tokio fu, where there is a little grave with a tombstone over

it and

the characters:  written

thereon. They mean Tomb

of Futetsu-shi, and it is here that Watanabe Tatsuzo is said to

have been

buried.

_________________________________ 1 Fukuga told

me this story and vouches for its accuracy. 2 Three Pines. |