| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Ancient Tales and Folk-Lore of Japan Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

THE KING OF TORIJIMA1 MANY

years ago there lived a Daimio called Tarao. His castle and home were at Osaki,

in Osumi Province, and amongst his retinue was a faithful and favourite servant

whose name was Kume Shuzen. Kume had long been land-steward to the Lord Tarao,

and indeed acted for him in everything connected with business. One

day Kume had been despatched to the capital, Kyoto, to attend to business for

his master, when the Daimio Toshiro of Hyuga quarrelled with the Daimio of

Osumi over some boundary question, and, Kume not being there to help his

master, who was a hasty person, the two clans fought at the foot of Mount

Kitamata. The

Lord Tarao of Osumi was killed, and so were most of his men. They were most

completely beaten. The survivors retired to their lord's castle at Osaki; but

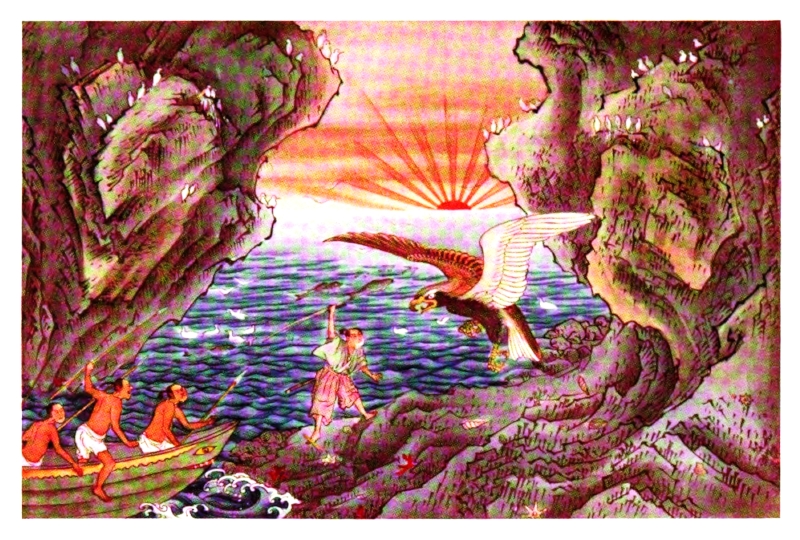

the enemy followed them up, and again defeated them, taking the castle. Messengers had been despatched to bring back Kume, of course; but Kume decided that there was only one honourable thing to do, and that was to gather the few remaining samurai he could and fight again in his dead master's behalf. Unfortunately, only some fifty men came to his call. These, with Kume, hid in the mountains with the intention of waiting until they had recruited more. One of Toshiro's spies found this out, and all except Kume were taken prisoners.  Kume Slays the Eagle, Torijima Being

hotly pursued, Kume hid himself in the daytime, and made for the sea by night.

After three clays he reached Hizaki, and there, having bought all the provision

he could carry, hid himself until an opportunity should come of seizing a boat

in the darkness, hoping to baffle his pursuers. Kume

was no sailor; in fact, he had hardly ever been in a boat, and never except as

a passenger. There was no difficulty in finding a boat. He pushed it off and

let it drift, for he could not use the oar, and understood nothing about a

sail. Fortunately, Hizaki is a long cape on the S.E. coast, facing the open

Pacific, and therefore there was no difficulty in getting away, the wind being

favourable and the tide as well; besides, there is here a strong current always

travelling south towards the Loochoos. Kume was more or less indifferent as to

where he went, and even if he had cared he could not have helped himself, for,

though his knowledge of direction on land was very good, as soon as he found

himself out of sight of land he was lost. All he knew was that where the sun

rose there was no land which he could reach, that China lay in the direction in

which it set, and that to the south there were islands which were reputed to

hold savages, Nambanjin (foreign southern savages). Thus Kume drifted on, he

knew not whither, lying in the bottom of the boat, and in no way economising

his provisions; and it naturally came to pass that at the end of the second day

he had no water left, and suffered much in consequence. Towards

morning on the fifth day Kume lay half-asleep in the bottom of the boat.

Suddenly he felt it bump. 'What

ho, she bumps!' said he to himself in his native tongue, and, sitting up, he

found he had drifted on to a rocky island. Kume was not long in scrambling

ashore and dragging his boat as high as he was able. The first thing he set

about doing was to find water to quench his thirst. As he wandered along the

rocky shore hunting for a stream, Kume knew that the island could not be

inhabited, for there were tens of thousands of sea-fowl perched upon the rocks,

feeding along the beach and floating on the water; others were sitting on eggs.

Kume could see that he was not likely to starve while the birds were breeding,

and he could see, moreover, that fish were there in abundance, for birds of the

gannet species were simply gorging themselves with a kind of iwashi (sardine),

which made the surface of the calm sea frizzle into foam in their endeavours to

escape the larger fish that were pursuing them from underneath. Shoals of

flying-fish came quite close to shore, pursued by the magnificent albacore;

which clearly showed that fishermen did not visit these parts. Shell-fish were

in plenty in the coral pools, and among them lay, thickly strewn, the smaller

of the pearl mussels with which Kume was familiar in his own country. There

was no sand on this island that is to say, on the seashore. Everything seemed

to be of coral formation, except that there was a thick reddish substance on

the top of all, out of which grew low scrubby trees bearing many fruits, which

Kume found quite excellent to eat. There was no trouble in finding water: there

were several streams flowing down the beach and coming from the thick scrub. Kume

returned to his boat, to make sure that it was safe, and, having found a better

cove for it, he moved it thither. Then, having eaten some more fruit and

shellfish and seaweed, Kume lay down to sleep, and to think of his dead master,

and wonder how he could eventually avenge him on the Daimio Toshiro of Hyuga. When

morning broke Kume was not a little surprised to see some eight or nine figures

of people, as he first thought, sleeping; but when it grew lighter he found

that they were turtles, and it was not long before he was on shore and had

turned one; but then, recollecting that there was plenty of food without taking

the life of a beast so much venerated, he let it go. 'Perhaps,' thought he,

like Urashima, my kindness to the turtle may save me. Indeed, these turtles may

be messengers or retainers of the Sea King's Palace!' One

thing that Kume now decided was to learn to row and sail his boat. He set to

that very morning, and almost mastered the art of using the immense sculling

oar used by present and ancient Japanese alike. In the afternoon he visited the

highest part of his island; but it was not high enough to enable him to see

land, though he thought at one time that he could discern that faint line of

blue on the horizon which prophesies distant land. However,

he was safe for the time; he had food in plenty, and water; true, the birds

somewhat bothered him, for they did not act as might have been expected. There

seemed something uncanny in the way they sat on their perches and watched him.

He did not like that, and often threw a stone at them; but even that had little

effect they only seemed to look more serious. Though

Kume was no sailor, he was a good enough swimmer, as are most Japanese who live

anywhere along the sea provinces, and he was quite able to dive in moderation

and up to a depth of three Japanese fathoms fifteen feet. Thus it was that

Kume spent all the time he was not practising in his boat in diving for

shellfish; he soon found that there were enormous quantities of pearl oysters,

which contained beautiful pearls; and, having collected some fifty or sixty,

large and small, he cut one of the sleeves of his coat and made a bag which he

determined to fill. One day while Kume was diving about after his pearls and

shell-fish, he found that by looking in the holes of rocks beneath the low-tide

level he could find pearls that had fallen from the dead and rotten shells

above; in one case they were like gravel, and he took them out of a cavity by

handfuls. Discoloured they certainly were; but Kume knew them from their

roundness of shape, and rubbing with sand or earth soon proved them to be

pearls. Thus it was that he worked with renewed energy, hoping all the time to

make sufficient money to be able eventually to avenge his dead master. One

day, some six weeks after he had landed on the island, he saw a distant sail.

Through the day he watched it carefully; but it did not seem to come or go much

nearer, and Kume came to the conclusion that it must be the sail of a

stationary fishing-boat, for there was breeze enough to have taken it oil out

of sight twice over since he had watched, if it had wanted to go. 'Surely

there must be land somewhere over there beyond the boat: it would not be there

for half a day if not. To-morrow, now that I can manage to sail and row my

boat, I will start on an expedition and see. I do not expect to find my own

countrymen there; but I may find Chinese who may be friendly, and if I find the

southern savages I shall not, with my good Japanese sword, be afraid of them!' Next

morning Kume provisioned his boat with fruit, water, shell-fish, and eggs, and,

tying his bag of pearls about him, set sail in a south-westerly direction.

There was little wind, and the boat went slowly; but Kume steered steadily all

night, as was natural, considering the little he knew. He dared not go to sleep

and thus perhaps lose all idea of the direction whence he had come. Thus it

came that when morning broke the sun rose on his port side, and he found

himself not more than some four miles from an island which lay right ahead of

him. Quite elated with his first success in navigation, Kume seized his oars

and helped the boat along. On reaching the land his reception was anything but

pleasant. At least one hundred angry savages were on the beach with spears and

staves; but what were they (as my translator asks) to a Japanese samurai?

Fifteen of them were put out of action without his getting a scratch, for Kume

was well up in all the defensive arts that his military training had given him,

and the tricks in jujitsu were familiar to him. The

rest of his adversaries became frightened and began to run. Kume caught one of

them, and tried to ask what island this was, and what kind of people they were.

By signs he explained that he was a Japanese and in no way an enemy, but on the

contrary wished to be friendly, and, as they could see, he was alone. Greatly

impressed with Kume's prowess, and glad that he did not wish to resume

hostilities, the natives stuck their spears point-downwards in the sand, and

came forward to Kume, who sheathed his sword and proceeded to examine the

fifteen men he had laid low. Eleven of these had fallen by some clever jujitsu

trick, and were to all intents and purposes dead; but Kume took them in various

ways and restored them to life by a well-known art called kwatsu (really

artificial breathing), which has been practised in Japan for hundreds of years

in connection with some secret jujitsu tricks which are said to kill you unless

some one is present who knows the art of kwatsu you must die if left for over

two hours without being restored. At present it is illegal to kill temporarily

even though you know the art of kwatsu. Kume restored nine of his fallen

enemies, which in itself was considered to be a marvellous performance, and

gained him much respect. Two others were dead. The rest had wounds from which

they recovered. Peace

being established, Kume was escorted by the chief to the village and given a

hut to himself, and he found the people kind and agreeable. A wife was given to

him, and Kume settled down to the life of the island, and to learn the

language, which in many ways resembled his own. Sugar

and yams were the principal things planted, with, of course, rice in the

hills and where there was sufficient water for terracing, but fishing formed

the principal occupation of all. Four or five times a-year the islanders were

visited by a junk which bought their produce, and exchanged things they wanted

for it such as beds, iron rods, calico, and salt. After three months'

residence Kume was able to talk the language a little, and had managed to

narrate his adventures; moreover, he had explained that the island from which

he had sailed he had named it Torijima, 1 on

account of the birds there was a far better island than their own for all

marine produce. 'Do, my friends,' said Kume, 'accompany me over there and see.

I have shown you my pearls. I am not much of a diver; but, for those that are

divers there are as many as you can wish also sea-slugs, bκche-de-mer, and

namako of the very best kinds.' 'Do

you know that the island which you call "Tori" is bewitched?' they

asked. 'It is impossible to go there, for there is a gigantic bird which comes

twice a-year and kills all men who have ventured to land. It could not have

been there when you were, or you could not have lived a day.' 'Well,

my friends,' said Kume, 'I am not afraid of a bird, and, as you have been very

kind to me, I should like to show you my Torijima, for, though small, it is

better than your island for all the things which come from the sea, and you

would say so if you came. Please say that some of you will accompany me.' At

last thirty men said they would go; that would be three boat-loads of them. Accordingly,

next evening they started, and, as the direction was well known to the

Loochooans, they reached the shores of Torijima just as the sun arose. Kume's

boat arrived first. Though he had been fully warned of the great bird which

must have been absent when he was in the island, Kume landed alone, and was

proceeding up the shore when an immense eagle with a body larger than his own

swept down on him and began to fight. Kume, being a Japanese, immediately cut

the monster in half. From

that day Torijima has been settled on by fishermen, and has afforded more

pearls, coral, and fish than the other, which they named Kumijima, and

sometimes Shuzen shima (both being his names); moreover, Kume Shuzen was made

the king of both islands. Kume never got back to Japan to avenge his master the

Lord Tarao. Indeed, he was better off than he had ever been before, and lived a

happy life on the two wild Loochoo islands, which had not yet come under the

Chinese rule, being too small to be thought of. After some fifteen years Kume died and was buried on Kumijima. My story-teller says that those who visit the Loochoos and pass Kumijima will notice from the sea a monument erected to Kume Shuzen. ____________________________________-

2 Tori-bird Island. |