| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Ancient Tales and Folk-Lore of Japan Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| THE DIVING-WOMAN OF OISO BAY OISO,

in the Province of Sagami, has become such a celebrated place as the

chosen

residence of the Marquis Ito and of several other high Japanese

personages,

that a story of a somewhat romantic nature, dating back to the Ninan

period,

may be interesting. During

one of the earlier years of the period, which lasted from '116 to 1169

A. D., a

certain knight, whose name was Takadai Jiro, became ill in the town of

Kamakura, where he had been on duty, and was advised to spend the hot

month of

August at Oiso, and there to give himself perfect rest, peace, and

quietness. Having

obtained permission to do this, Takadai Jiro lost no time in getting to

the

place and settling himself down, as comfortably as was possible, in a

small inn

which faced the sea. Being a landsman who (with the exception of his

service at

Kamakura) had hardly ever seen the sea, Takadai was pleased to dwell in

gazing

at it both by day and by night, for, like most Japanese of high birth,

he was

poetical and romantic. After

his arrival at Oiso, Takadai felt weary and dusty. As soon as he had

secured

his room he threw off his clothes and went down to bathe. Takadai,

whose age

was about twenty-five years, was a good swimmer, and plunged into the

sea

without fear, going out for nearly half-a-mile. There, however,

misfortune

overtook him. He was seized with a violent cramp and began to sink. A

fishing-boat sculled by a man and containing a diving-girl happened to

see him

and went to the rescue; but by this time he had lost consciousness, and

had

sunk for the third time. The

girl jumped overboard and swam to the spot where he had disappeared,

and,

having dived deep, brought him to the surface, holding him there until

the boat

came up, when by the united efforts of herself and her father Takadai

was

hauled on board, but not before he had realised that the soft arm that

clung

round his neck was that of a woman. When he was thoroughly conscious again, before they had reached the shore, Takadai saw that his preserver was a beautiful ama (diving-girl) aged not more than seventeen. Such beauty he had never seen before — not even in the higher circles in which he was accustomed to move. Takadai was in love with his brave saviour before the boat had grounded on the pebbly beach. Determined in some way to repay the kindness he had received, Takadai helped to haul their boat up the steep beach and then to carry their fish and nets to their little thatched cottage, where he thanked the girl for her noble and gallant act in saving him, and congratulated her father on the possession of such a daughter. Having done this, he returned to his inn, which was not more than a few hundred yards away.  O Kinu San Inspects the Place Where Takadai Jiro Committed Suicide From

that time on the soul of Takadai knew no peace. Love of the maddest

kind was on

him. There was no sleep for him at night, for he saw nothing but the

face of

the beautiful diving-girl, whose name (he had ascertained) was Kinu.

Try as he

might, he could not for a moment put her out of his mind. In the

daytime it was

worse, for O Kinu was not to be seen, being out at sea with her father,

diving

for the haliotis shell and others; and it was generally the dusk of

evening

before she returned, and then, in the dim light, he could not see her. Once,

indeed, Takadai tried to speak to O Kinu; but she would have nothing to

say to

him, and continued busying herself in assisting her father to carry the

nets

and fish up to their cottage. This made Takadai far worse, and he went

home

wild, mad, and more in love than ever. At

last his love grew so great that he could endure it no longer. He felt

that at

all events it would be a relief to declare it. So he took his most

confidential

servant into the secret, and despatched him with a letter to the

fisherman's

cottage. O Kinu San did not even write an answer, but told the old

servant to

thank his master in her behalf for his letter and his proposal of

marriage.

'Tell him also,' said she, 'that no good could come of a union between

one of

so high a birth as he and one so lowly as I. Such a badly matched pair

could

never make a happy home.' In answer to the servant's expostulation, she

merely

added, 'I have told you what to tell your master: take him the

message.' Takadai

Jiro, on hearing what O Kinu had said, was not angry. He was simply

astonished.

It was beyond his belief that a fisher-girl could refuse such an offer

in

marriage as himself — a samurai of the upper class. Indeed, instead of

being

angry, Takadai was so startled as to be rather pleased than otherwise;

for he

thought that perhaps he had taken the fair O Kinu San a little too

suddenly,

and that this first refusal was only a bit of coyness on her part that

was not

to be wondered at. 'I will wait a day or two,' thought Takadai. 'Now

that Kinu

knows of my love, she may think of me, and so become anxious to see me.

I will

keep out of the way. Perhaps then she will be as anxious to see me as I

am to

see her.' Takadai

kept to his own room for the next three days, believing in his heart

that O

Kinu must be pining for him. On the evening of the fourth day he wrote

another

letter to O Kinu, more full of love than the first, despatched his old

servant,

and waited patiently for the answer. When

O Kinu was handed the letter she laughed and said: 'Truly,

old man, you appear to me very funny, bringing me letters. This is the

second

in four days, and never until four days ago have I had a letter

addressed to me

in my life. What is this one about, I wonder?' Saying

this, she tore it open and read, and then, turning to the servant,

continued:

'It is difficult for me to understand. If you gave my message to your

master

correctly he could not fail to know that I could not marry him. His

position in

life is far too high. Is your master quite right in his head?' 'Yes:

except for the love of you, my young master is quite right in his head;

but

since he has seen you he talks and thinks of nothing but you, until

even I have

got quite tired of it, and earnestly pray to Kwannon daily that the

weather may

get cool, so that we may return to our duties at Kamakura. For three

full days

have I had to sit in the inn listening to my young master's poems about

your

beauty and his love. And I had hoped that every day would find us

fishing from

a boat for the sweet aburamme fish, which are now fat and good, as

every other

sensible person is doing. Yes: my master's head was right enough; but

you have

unsettled it, it seems. Oh, do marry him, so that we shall all be happy

and go

out fishing every day and waste no more of this unusual holiday.' 'You

are a selfish old man,' answered O Kinu. 'Would you that I married to

satisfy

your master's love and your desire for fishing? I have told you to tell

your

master that I will not marry him, because we could not, in our

different ranks

of life, become happy. Go and repeat that answer.' The

servant implored once more; but O Kinu remained firm, and finally he

was

obliged to deliver the unpleasant message to his master. Poor

Takadai! This time he was distressed, for the girl had even refused to

meet

him. What was he to do? He wrote one more imploring letter, and also

spoke to O

Kinu's father; but the father said, 'Sir, my daughter is all I have to

love in

the world: I cannot influence her in such a thing as her love.

Moreover, all

our diving-girls are strong in mind as well as in body, for constant

danger

strengthens their nerves: they are not like the weak farmers' girls,

who can be

influenced and even ordered to marry men they hate. Their minds are,

oftener

than not, stronger than those of us men. I always did what Kinu's

mother told

me I was to do, and could not influence Kinu in such a thing as her

marriage. I

might give you my advice, and should do so; but, sir, in this case I

must agree

with my daughter, that, great as the honour done to her, she would be

unwise to

marry one above her own station in life.' Takadai's

heart was broken. There was nothing more that he could say and nothing

more

that he could do. Bowing low, he left the fisherman and retired

forthwith to

his room in the inn, which he never left, much to the consternation of

his

servant. Day

by day he grew thinner, and as the day approached for his return from

leave,

Takadai was far more of an invalid than he had been on his arrival at

Oiso.

What was he to do? The sentiment of the old proverb that 'there are as

good

fish in the sea as ever came out of it' did not in any way appeal to

him. He

felt that life was no longer worth having. He resolved to end it in the

sea,

where his spirit might perhaps linger and catch sight occasionally of

the

beautiful diving-girl who had bewitched his heart. Takadai

that evening wrote a last note to Kinu, and as soon as the villagers of

Oiso

were asleep he arose and went to the cottage, slipping the note under

the door.

Then he went to the beach, and, after tying a large stone to a rope and

to his

neck, he got into a boat and rowed himself about a hundred yards from

shore,

where he took the stone in his arms and jumped overboard. Next

morning O Kinu was shocked to read in the note that Jiro Takadai was to

kill

himself for love of her. She rushed down to the beach, but could see

only an

empty fishing-boat some three or four hundred yards from shore, to

which she

swam. There she found Takadai's tobacco box and his juro (medicine

box). O Kinu

thought that Takadai must have thrown himself into the sea somewhere

hereabouts: so she began to dive, and was not long before she found the

body,

which she brought to the surface, after some trouble on account of the

weight

of the stone which the arms rigidly grasped. O Kinu took the body back

to

shore, where she found Takadai's old servant wringing his hands in

grief. The

body was taken back to Kamakura, where it was buried. O Kinu was

sufficiently

touched to vow that she would never marry any one. True, she had not

loved

Takadai; but he had loved, and had died for her. If she married, his

spirit

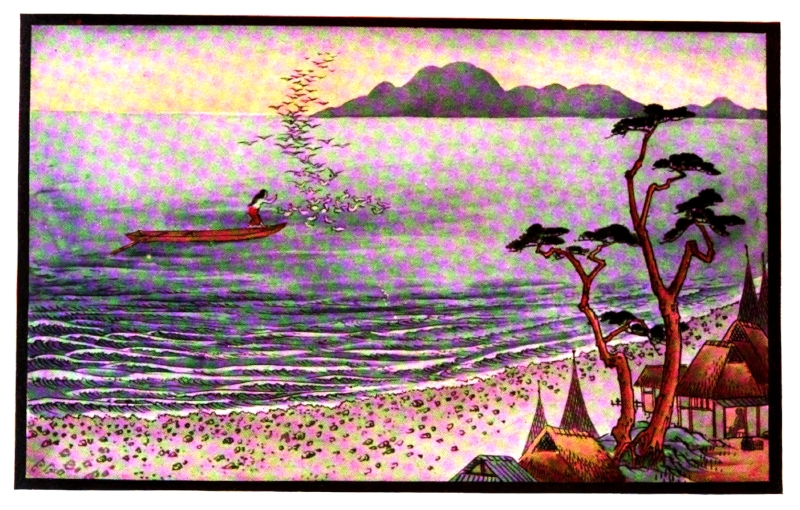

would not rest in peace. No

sooner had O Kinu mentally undertaken this generous course than a

strange thing

came to pass. Sea-gulls,

which were especially uncommon in Oiso Bay, began to swarm into it;

they

settled over the exact spot where Takadai had drowned himself. In

stormy

weather they hovered over it on the wing; but they never went away from

the

place. Fishermen thought it extraordinary; but Kinu knew well enough

that the

spirit of Takadai must have passed into the gulls, and for it she

prayed

regularly at the temple, and out of her small savings built a little

tomb

sacred to the memory of Takadai Jiro. By

the time Kinu was twenty years of age her beauty was celebrated, and

many were

the offers she had in marriage; but she refused them all, and kept her

vow of

celibacy. During her entire life the sea-gulls were always on the spot

where

Takadai had been drowned. She died by drowning in a severe typhoon some

nine

years later than Takadai; and from that day the sea-gulls disappeared,

showing

that his spirit was now no longer in fear of O Kinu marrying. |