| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

| I THE GOLDEN HAIRPIN 1 UP in

the northern city of Sendai, whence come the best of Japanese soldiers,

there

lived a samurai named Hasunuma. Hasunuma

was rich and hospitable, and consequently much thought of and well

liked. Some

thirty-five years ago his wife presented him with a beautiful daughter,

their

first child, whom they called 'Ko,' which means 'Small' when applied to

a

child, much as we say 'Little Mary or Little Jane.' Her full name was

really

'Hasu-ko,' which means 'Little Lily'; but here we will call her 'Ko'

for short.

Exactly

on the same date, 'Saito,' one of Hasunuma's friends and also a

samurai, had

the good fortune to have a son. The fathers decided that, being such

old

friends, they would wed their children to each other when old enough to

marry;

they were very happy over the idea, and so were their wives. To make

the

engagement of the babies more binding, Saito handed to Hasunuma a

golden

hairpin which had long been in his family, and said: 'Here,

my old friend, take this pin. It shall be a token of betrothal from my

son,

whose name shall be K˘noj˘, to your little daughter Ko, both of whom

are now

aged two weeks only. May they live long and happy lives together.' Hasunuma

took the pin, and handed it to his wife to keep; then they drank sakÚ

to the

health of each other, and to the bride and bridegroom of some twenty

years

thence. A few

months after this Saito, in some way, caused displeasure to his feudal

lord,

and, being dismissed from service, left Sendai with his family —

whither no one

knew. Seventeen

years later O Ko San was, with one exception, the most beautiful girl

in all

Sendai; the exception was her sister, O Kei, just a year younger, and

as

beautiful as herself. Many were the suitors for O Ko's hand; but she would have none of them, being faithful to the engagement made for her by her father when she was a baby. True, she had never seen her betrothed, and (which seemed more curious) neither she nor her family had ever once heard of the Saito family since they had left Sendai, over sixteen years before; but that was no reason why she, a Japanese girl, should break the word of her father, and therefore O Ko San remained faithful to her unknown lover, though she sorrowed greatly at his non-appearance; in fact, she secretly suffered so much thereby that she sickened, and three months later died, to the grief of all who knew her and to her family's serious distress.  The Spirit of O Ko Appears to Konoj˘ as O Kei San On

the day of O Ko San's funeral her mother was seeing to the last

attentions paid

to corpses, and smoothing her hair with the golden pin given to Ko San

or O Ko2 by Saito in behalf of his son K˘noj˘. When the

body had been placed in its coffin, the mother thrust the pin into the

girl's

hair, saying: 'Dearest

daughter, this is the pin given as a memento to you by your betrothed,

K˘noj˘.

Let it be a pledge to bind your spirits in death, as it would have been

in

life; and may you enjoy endless happiness, I pray.' In

thus praying, no doubt, O Ko's mother thought that K˘noj˘ also must be

dead,

and that their spirits would meet; but it was not so, for two months

after

these events K˘noj˘ himself, now eighteen years of age, turned up at

Sendai,

calling first on his father's old friend Hasunuma. 'Oh,

the bitterness and misfortune of it all!' said the latter. 'Only two

months ago

my daughter Ko died. Had you but come before then she would have been

alive

now. But you never even sent a message; we never heard a word of your

father or

of your mother. Where did you all go when you left here? Tell me the

whole

story.' 'Sir,'

answered the grief-stricken K˘noj˘, 'what you tell me of the death of

your

daughter, whom I had hoped to marry, sickens my heart, for I, like

herself, had

been faithful, and I hoped to marry her, and thought daily of her. When

my

father took my family away from Sendai, he took us to Yedo; and

afterwards we

went north to Yezo Island, where my father lost his money and became

poor. He

died in poverty. My poor mother did not long survive him. I have been

working

hard to try and earn enough to marry your daughter Ko; but I have not

made more

than enough to pay my journey down to Sendai. I felt it my duty to come

and

tell you of my family's misfortune and my own.' The

old samurai was much touched by this story. He saw that the most

unfortunate of

all had been K˘noj˘. 'K˘noj˘,'

he said, 'often have I thought and wondered to myself, Were you honest

or were

you not? Now I find that you have been truly faithful, and honest to

your

father's pledge. But you should have written — you should have written!

Because

you did not do so, sometimes we thought, my wife and I, that you must

be dead;

but we kept this thought to ourselves, and never told Ko San. Go to our

Butsudan;3

open the doors of it, and burn a joss stick to Ko San's mortuary

tablet. It

will please her spirit. She longed and longed for your return, and died

of that

sane longing — for love of you. Her spirit will rejoice to know that

you have

come back for her.' K˘noj˘

did as he was bid. Bowing

reverently three times before the mortuary tablet of O Ko San, he

muttered a

few words of prayer in her behalf, and then lit the incense-stick and

placed it

before the tablet. After

this exhibition of sincerity Hasunuma told the young fellow that he

should

consider him as an adopted son, and that he must live with them. He

could have the

small house in the garden. In any case, whatever his plans for the

future might

be, he must remain with them for the present. This

was a generous offer, worthy of a samurai. K˘noj˘ gratefully accepted

it, and

became one of the family. About a fortnight afterwards he settled

himself in

the little house at the end of the garden. Hasunuma, his wife, and

their second

daughter, O Kei, had gone, by command of the Daimio, to the Higan, a

religious

ceremony held in March; Hasunuma also always worshipped at his

ancestral tombs

at this time. Towards the dusk of evening they were returning in their

palanquins. K˘noj˘ stood at the gate to see them pass, as was proper

and

respectful. The old samurai passed first, and was followed by his

wife's

palanquin, and then by that of O Kei. As this last passed the gate

K˘noj˘

thought he heard something fall, causing a metallic sound. After the

palanquin

had passed he picked it up without any particular attention. It

was the golden hairpin; but of course, though K˘noj˘'s father had told

him of

the pin, K˘noj˘ had no idea that this was it, and therefore he thought

nothing

more than that it must be O Kei San's. He went back to his little

house, closed

it for the night, and was about to retire when he heard a knock at the

door.

'Who is there?' he shouted. 'What do you want?' There came no answer,

and

K˘noj˘ lay down on his bed, thinking himself to have been mistaken. But

there

came another knock, louder than the first; and K˘noj˘ jumped out of

bed, and

lit the ando.4 'If not a fox or a badger,' thought

he, 'it must be some evil spirit come to disturb me.' On

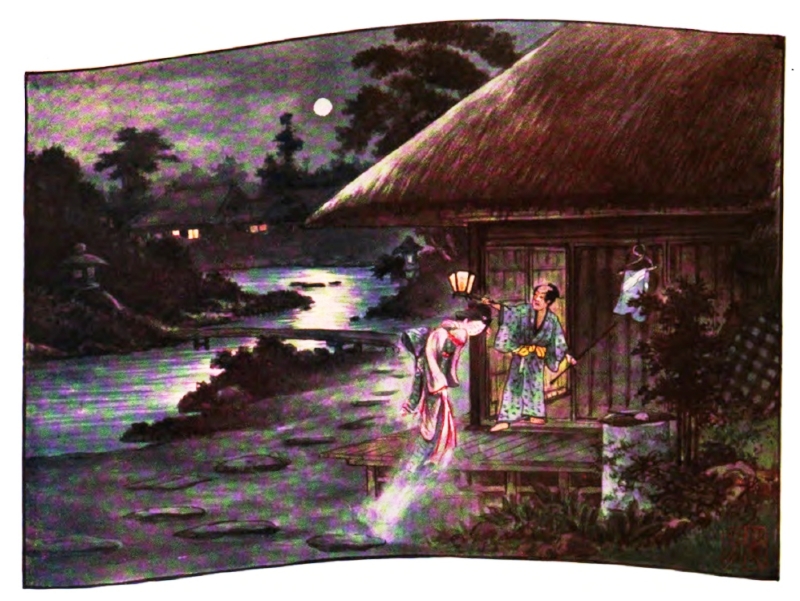

opening the door, with the ando in one hand, and a stick in the other,

K˘noj˘

looked out into the dark, and there, to his astonishment, he beheld a

vision of

female beauty the like of which he had never seen before. 'Who are you,

and

what do you want?' quoth he. 'I am

O Kei San, O Ko's younger sister,' answered the vision. 'Though you

have not seen

me, I have several times seen you, and I have fallen so madly in love

with you

that I can think of nothing else but you. When you picked up my golden

pin

to-night on our return, I had dropped it to serve as an excuse to come

to you

and knock. You must love me in return; for otherwise I must die!' This

heated and outrageous declaration scandalised poor K˘noj˘. Moreover, he

felt

that it would be doing his kind host Hasunuma a great injustice to be

receiving

his younger daughter at this hour of the night and make love to her. He

expressed himself forcibly in these terms. 'If

you will not love me as I love you, then I shall take my revenge,' said

O Kei,

'by telling my father that you got me to come here by making love to

me, and

that you then insulted me.' Poor

K˘noj˘! He was in a nice mess. What he feared most of all was that the

girl

would do as she said, that the samurai would believe her, and that he

would be

a disgraced and villainous person. He gave way, therefore, to the

girl's

request. Night after night she visited him, until nearly a month had

passed.

During this time K˘noj˘ had learned to love dearly the beautiful O Kei.

Talking

to her one evening, he said: 'My

dearest O Kei, I do not like this secret love of ours. Is it not better

that we

go away? If I asked your father to give you to me in marriage he would

refuse,

because I was betrothed to your sister.' 'Yes,'

answered O Kei: 'that is what, I also have been wishing. Let us leave

this very

night, and go to Ishinomaki, the place where (you have told me) lives a

faithful servant of your late father's, called Kinzo.' 'Yes:

Kinzo is his name, and Ishinomaki is the place. Let us start as soon as

possible.' Having

thrust a few clothes into a bag, they started secretly and late that

night, and

duly arrived at their destination. Kinzo was delighted to receive them,

and

pleased to show how hospitable he could be to his late master's son and

the

beautiful lady. They

lived very happily for a year. Then one day O Kei said: 'I

think we ought to return, to my parents now. If they were angry with us

at

first they will have got over the worst of it. We have never written.

They must

be getting anxious as to my fate as they grow older. Yes: we ought to

go.' K˘noj˘

agreed. Long had he felt the injustice he was doing Hasunuma. Next

day they found themselves back in Sendai, and K˘noj˘ could not help

feeling a

little nervous as he approached the samurai's house. They stopped at

the outer

gate, and O Kei said to K˘noj˘, 'I think it will be better for you to

go in and

see my father and mother first. If they get very angry show them this

golden

pin. K˘noj˘

stepped boldly up to the door, and asked for an interview with the

samurai. Before

the servant had time to return, K˘noj˘ heard the old man shout, 'K˘noj˘

San!

Why, of course! Bring the boy in at once,' and he himself came out to

welcome

him. 'My

dear boy,' said the samurai, 'right glad am I to see you back again. I

am sorry

you did not find your life with us good enough. You might have said you

were

going. But there — I suppose you take after your father in these

matters, and

prefer to disappear mysteriously. You are welcome back, at all events.'

K˘noj˘

was astonished at this speech, and answered: 'But,

sir, I have come to beg pardon for my sin.' 'What

sin have you committed?' queried the samurai in great surprise, and

drawing

himself up, in a dignified manner. K˘noj˘

then gave a full account of his love-affair with O Kei. From beginning

to end

he told it all, and as he proceeded the samurai showed signs of

impatience. 'Do

not joke, sir! My daughter O Kei San is not a subject for jokes and

untruths.

She has been as one dead for over a year — so ill that we have with

difficulty

forced gruel into her mouth. Moreover, she has spoken no word and shown

no sign

of life.' 'I am

neither stating what is untrue nor joking,' said K˘noj˘. 'If you but

send

outside, you will find O Kei in the palanquin, in which I left her.' A

servant was immediately sent to see, and returned, stating that there

was

neither palanquin nor any one at the gate. K˘noj˘,

seeing that the samurai was now beginning to look perplexed and angry,

drew the

golden pin from his clothes, saying: 'See!

if you doubt me and think I am lying, here is the pin which O Kei told

me to

give you!' 'Bik-ku-ri-shi-ta-!'

5

exclaimed O Kei's mother. 'How came this pin into your hands? I myself

put it

into Ko San's coffin just before it was closed.' The

samurai and K˘noj˘ stared at each other, and the mother at both.

Neither knew

what to think, or what to say or do. Imagine the general surprise when

the sick

O Kei walked into the room, having risen from her bed as if she had

never been

ill for a moment. She was the picture of health and beauty. 'How

is this?' asked the samurai, almost shouting. 'How is it, O Kei, that

you have

come from your sickbed dressed and with your hair done and looking as

if you

had never known a moment of illness?' 'I am

not O Kei, but the spirit of O Ko,' was the answer. 'I was most

unfortunate in

dying before the return of K˘noj˘ San, for had I lived until then I

should have

become quite well and been married to him. As it was, my spirit was

unhappy. It

took the form of my dear sister O Kei, and for a year has lived happily

in her

body with K˘noj˘. It is appeased now, and about to take its real rest.'

'There

is one condition, however, K˘noj˘, which I must make,' said the girl,

turning

to him. 'You must marry my sister O Kei. If you do this my spirit will

rest

truly in peace, and then O Kei will become well and strong. Will you

promise to

marry O Kei?' The

old samurai, his wife, and K˘noj˘ were all amazed at this. The

appearance of

the girl was that of O Kei; but the voice and manners were those of O

Ko. Then,

there was the golden hairpin as further proof. The mother knew it well.

She had

placed it in Ko's hair just before the tub coffin was closed. Nobody

could

undeceive her on that point. 'But,'

said the samurai at last, 'O Ko has been dead and buried for more than

a year

now. That you should appear to us puzzles us all. Why should you

trouble us

so?' 'I

have explained already,' resumed the girl. 'My spirit could not rest

until it

had lived with K˘noj˘, whom it knew to be faithful. It has done this

now, and

is prepared to rest. My only desire is to see K˘noj˘ marry my sister.' Hasunuma,

his wife, and K˘noj˘ held a consultation. They were quite prepared that

O Kei

should marry, and K˘noj˘ did not object. All

things being settled, the ghost-girl held out her hand to K˘noj˘

saying: 'This

is the last time you will touch the hand of O Ko. Farewell, my dear

parents!

Farewell to you all! I am about to pass away.' Then

she fainted away, and seemed dead, and remained thus for half an hour;

while

the others, overcome with the strange and weird things which they had

seen and

heard, sat round her, hardly uttering a word. At

the end of half an hour the body came to life, and standing up, said: 'Dear

parents, have no more fear for me. I am perfectly well again; but I

have no

idea how I got down from my sick-room in this costume, or how it is

that I feel

so well.' Several

questions were put to her; but it was quite evident that O Kei knew

nothing of

what had happened — nothing of the spirit of O Ko San, or of the golden

hairpin! A

week later she and K˘noj˘ were married, and the golden hairpin was

given to a

shrine at Shiogama, to which, until quite recently, crowds used to go

and

worship. 1 This story

savours of 'Botan D˘r˘,' or Peony Lantern story, told both by Mitford

and by

Lafcadio Hearn. In this instance, however, the spirit of the dead

sister passes

into the body of the living one, assumes her form, leaves her sick and

ill for

over a year, and then allows her to reappear as if she had never been

ill at

all. It is the first story of its kind I have heard. 2 'O' means

Honourable Miss; 'San' means Miss. Either will

do; but Ko is the name. 3 Family

shrine. 4 Lamp. 5 An

exclamation, such as 'Great Scot!' |