| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2014 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

NIGHT IN A CANOE

A dreary

world! The constant rain

Beats back to earth blithe fancy's wings; And life — a sodden garment — clings About a body numb with pain. Imagination ceased with light; Of Nature's psalm no echo lingers. The death-cold mist, with ghostly fingers, Shrouds world and soul in rayless night. An inky sea, a sullen crew, A frail canoe's uncertain motion; A whispered talk of wind and ocean, As plotting secret crimes to do! The vampire-night sucks all my blood; Warm home and love seem lost for aye; From cloud to cloud I steal away, Like guilty soul o'er Stygian flood. Peace, morbid heart! From paddle blade See the black water flash in light; And bars of moonbeams streaming white, Have pearls of ebon raindrops made. From darkest sea of deep despair Gleams Hope, awaked by Action's blow; And Faith's clear ray, though clouds hang low, Slants up to heights serene and fair. THE LOST GLACIER Springing ashore he said,

"When

can you be ready?" "Aren't you a little

fast?" I

replied. "What does this mean? Where's your wife?" "Man," he exclaimed,

"have you forgotten? Don't you know we lost a glacier last fall? Do you

think I could sleep soundly in my bed this winter with that hanging on

my

conscience? My wife could not come, so I have come alone and you've got

to go

with me to find the lost. Get your canoe and crew and let us be off." The ten months since Muir

had left me

had not been spent in idleness at Wrangell. I had made two long voyages

of

discovery and missionary work on my own account, — one in the spring, of

four

hundred fifty miles around Prince of Wales Island, visiting the five

towns of

Hydah Indians and the three villages of the Hanega tribe of Thlingets.

Another

in the summer down the coast to the Cape Fox and Tongass tribes of

Thlingets,

and across Dixon entrance to Ft. Simpson, where there was a mission

among the

Tsimpheans, and on fifteen miles further to the famous mission of

Father Duncan

at Metlakahtla. I had written accounts of these trips to Muir; but for

him the

greatest interest was in the glaciers and mountains of the mainland. Our preparations were

soon made. Alas!

we could not have our noble old captain, Tow-a-att, this time. On the

tenth of

January, 1880, — the darkest day of my

life, — this "noblest Roman of

them all" fell dead at my feet with a bullet through his forehead, shot

by

a member of that same Hootz-noo tribe where he had preached the gospel

of peace

so simply and eloquently a few months before. The Hootz-noos, maddened

by the

fiery liquor that bore their name, came to Wrangell, and a preliminary

skirmish

led to an attack at daylight of that winter day upon the Stickeen

village. Old

Tow-a-att had stood for peace, and rather than have any bloodshed had

offered

all his blankets as a peace offering, although in no physical fear

himself; but

when the Hootz-noos, encouraged by the seeming cowardice of the

Stickeens,

broke into their houses, and the Christianized tribe, provoked beyond

endurance, came out with their guns, Tow-a-att came forth armed only

with his

old carved spear, the emblem of his position as chief, to see if he

could not

call his tribe back again. At my instance, as I stood with my hand on

his

shoulder, he lifted up his voice to recall his people to their houses,

when, in

an instant, the volley commenced on both sides, and this Christian man,

one of

the simplest and grandest souls I ever knew, fell dead at my feet, and

the

tribe was tumbled back into barbarism; and the white man, who had

taught the

Indians the art of making rum, and the white man's government, which

had

afforded no safeguard against such scenes, were responsible.

The beautiful Davidson Glacier, with its great snow-white fan, drew our gaze and excited our admiration for two days. Muir mourned with me the

fate of this old chief; but another

of my men, Lot Tyeen, was ready with a swift canoe. Joe, his

son-in-law, and

Billy Dickinson, a half-breed boy of seventeen who acted as

interpreter,

formed the crew. When we were about to embark I suddenly thought of my

little

dog Stickeen and made the resolve to take him along. My wife and Muir

both

protested and I almost yielded to their persuasion. I shudder now to

think

what the world would have lost had their arguments prevailed ! That

little,

long-haired, brisk, beautiful, but very independent dog, in

co-ordination with

Muir's genius, was to give to the world one of its greatest

dog-classics.

Muir's story of "Stickeen" ranks with "Rab and His

Friends," "Bob, Son of Battle," and far above "The Call of

the Wild." Indeed, in subtle analysis of dog character, as well as

beauty

of description, I think it outranks all of them. All over the world

men, women

and children are reading with laughter, thrills and tears this

exquisite little

story. I have told Muir that in

his book he did not do justice to

my puppy's beauty. I think that he was the handsomest dog I have ever

known.

His markings were very much like those of an American Shepherd dog — black, white and tan; although he was not

half the size of one; but his hair was so silky and so long, his tail

so

heavily fringed and beautifully curved, his eyes so deep and

expressive and

his shape so perfect in its graceful contours, that I have never seen

another

dog quite like him; otherwise Muir's description of him is perfect. When Stickeen was only a

round ball of silky fur as big as

one's fist, he was given as a wedding present to my bride, two years

before

this voyage. I carried him in my overcoat pocket to and from the

steamer as we

sailed from Sitka to Wrangell. Soon after we arrived a solemn

delegation of

Stickeen Indians came to call on the bride; but as soon as they saw the

puppy

they were solemn no longer. His gravely humorous antics were

irresistible. It

was Moses who named him Stickeen after their tribe — an exceptional

honor.

Thereafter the whole tribe adopted and protected him, and woe to the

Indian

dog which molested him. Once when I was passing the house of this same

Lot

Tyeen, one of his large hunting dogs dashed out at Stickeen and began

to worry

him. Lot rescued the little fellow, delivered him to me and walked

into his

house. Soon he came out with his gun, and before I knew what he was

about he

had shot the offending Indian dog — a valuable hunting animal. Stickeen lacked the

obtrusively affectionate manner of many

of his species, did not like to be fussed over, would even growl when

our

babies enmeshed their hands in his long hair; and yet, to a degree I

have never

known in another dog, he attracted the attention of everybody and won

all

hearts. As instances: Dr.

Kendall, "The Grand Old Man" of

our Church, during his visit of 1879 used to break away from solemn

counsels

with the other D.D.s and the carpenters to run after and shout at

Stickeen. And

Mrs. McFarland, the Mother of Protestant missions in Alaska, often

begged us to

give her the dog; and, when later he was stolen from her care by an

unscrupulous tourist and so forever lost to us, she could hardly

afterwards

speak of him without tears. Stickeen was a born

aristocrat, dainty and scrupulously

clean. From puppyhood he never cared to play with the Indian dogs, and

I was

often amused to see the dignified but decided way in which he repulsed

all

attempts at familiarity on the part of the Indian children. He admitted

to his

friendship only a few of the natives, choosing those who had adopted

the white

man's dress and mode of living, and were devoid of the rank native

odors. His

likes and dislikes were very strong and always evident from the moment

of his

meeting with a stranger. There was something almost uncanny about the

accuracy

of his judgment when "sizing up" a man. It was Stickeen himself

who really decided the question

whether we should take him with us on this trip. He listened to the

discussion,

pro and con, as he stood with me on the wharf, turning his sharp,

expressive

eyes and sensitive ears up to me or down to Muir in the canoe. When the

argument seemed to be going against the dog he suddenly turned,

deliberately

walked down the gangplank to the canoe, picked his steps carefully to

the bow,

where my seat with Muir was arranged, and curled himself down on my

coat. The

discussion ended abruptly in a general laugh, and Stickeen went along.

Then the acute little

fellow set about, in the wisest

possible way, to conquer Muir. He was not obtrusive, never "butted

in"; never offended by a too affectionate tongue. He listened silently

to

discussions on his merits, those first days; but when Muir's

comparisons of the

brilliant dogs of his acquaintance with Stickeen grew too " odious "

Stickeen would rise, yawn openly and retire to a distance, not

slinkingly, but

with tail up, and lie down again out of earshot of such calumnies. When

we

landed after a day's journey Stickeen was always the first ashore,

exploring

for field mice and squirrels; but when we would start to the woods,

the

mountains or the glaciers the dog would join us, coming mysteriously

from the

forest. When our paths separated, Stickeen, looking to me for

permission, would

follow Muir, trotting at first behind him, but gradually ranging

alongside. After a few days Muir

changed his tone, saying,

"There's more in that wee beastie than I thought"; and before a week

passed Stickeen's victory was complete; he slept at Muir's feet, went

with him

on all his rambles; and even among dangerous crevasses or far up the

steep

slopes of granite mountains the little dog's splendid tail would be

seen ahead

of Muir, waving cheery signals to his new-found human companion. Our canoe was light and

easily propelled. Our outfit was

very simple, for this was to be a quick voyage and there were not to

be so

many missionary visits this time. It was principally a voyage of

discovery; we

were in search of the glacier that we had lost. Perched in the high

stern sat

our captain, Lot Tyeen, massive and capable, handling his broad

steering paddle

with power and skill. In front of him Joe and Billy pulled oars, Joe, a

strong

young man, our cook, hunter and best oarsman; Billy, a lad of

seventeen, our

interpreter and Joe's assistant. Towards the bow, just behind the

mast, sat

Muir and I, each with a paddle in his hands. Stickeen slumbered at our

feet or

gazed into our faces when our conversation interested him. When we

began to

discuss a landing place he would climb the high bow and brace himself

on the top

of the beak, an animated figure-head, ready to jump into the water when

we were

about to camp. Our route was different

from that of '79. Now we struck

through Wrangell Narrows, that tortuous and narrow passage between

Mitkof and

Kupreanof Islands, past Norris Glacier with its far-flung shaft of ice

appearing above the forests as if suspended in air; past the bold Pt.

Windham

with its bluff of three thousand feet frowning upon the waters of

Prince

Frederick Sound; across Port Houghton, whose deep fiord had no ice in

it and,

therefore, was not worthy of an extended visit. We made all haste, for

Muir

was, as the Indians said, " always hungry for ice," and this was more

especially his expedition. He was the commander now, as I had been the

year

before. He had set for himself the limit of a month and must return by

the

October boat. Often we ran until late at night against the protests of

our

Indians, whose life of infinite leisure was not accustomed to such

rude

interruption. They could not understand Muir at all, nor in the least

comprehend his object in visiting icy bays where there was no chance of

finding

gold and nothing to hunt. The vision rises before

me, as my mind harks back to this

second trip of seven hundred miles, of cold, rainy nights, when, urged

by Muir

to make one more point, the natives passed the last favorable camping

place and

we blindly groped for hours in pitchy darkness, trying to find a

friendly

beach. The intensely phosphorescent water flashed about us, the only

relief to

the inky blackness of the night. Occasionally a salmon or a big

halibut,

disturbed by our canoe, went streaming like a meteor through the water,

throwing off coruscations of light. As we neared the shore, the waves

breaking

upon the rocks furnished us the only illumination. Sometimes their

black tops

with waving seaweed, surrounded by phosphorescent breakers, would have

the

appearance of mouths set with gleaming teeth rushing at us out of the

dark as

if to devour us. Then would come the landing on a sandy beach, the

march

through the seaweed up to the wet woods, a fusillade of exploding fucus

pods accompanying

us as if the outraged fairies were bombarding us with tiny guns. Then

would

ensue a tedious groping with the lantern for a camping place and for

some dry,

fat spruce wood from which to coax a fire; then the big camp-fire, the

bean-pot

and coffee-pot, the cheerful song and story, and the deep, dreamless

sleep that

only the weary voyageur or hunter can know. Four or five days

sufficed to bring us to our first

objective — Sumdum or Holkham Bay, with its three wonderful arms. Here

we were

to find the lost glacier. This deep fiord has two great prongs. Neither

of them

figured in Vancouver's chart, and so far as records go we were the

first to

enter and follow to its end the longest of these, Endicott Arm. We

entered the

bay at night, caught again by the darkness, and groped our way

uncertainly. We

probably would have spent most of the night trying to find a landing

place had

not the gleam of a fire greeted us, flashing through the trees,

disappearing

as an island intervened, and again opening up with its fair ray as we

pushed

on. An hour's steady paddling brought us to the camp of some Cassiar

miners —

my friends. They were here at the foot of a glacier stream, from the

bed of

which they had been sluicing gold. Just now they were in hard luck, as

the constant

rains had swelled the glacial stream, burst through their wing-dams,

swept away

their sluice-boxes and destroyed the work of the summer. Strong men of

the wilderness

as they were, they were not discouraged, but were discussing plans for

prospecting new places and trying it again here next summer. Hot

coffee and

fried venison emphasized their welcome, and we in return could give

them a

little news from the outside world, from which they had been shut off

completely for months. Muir called us before

daylight the next morning. He had been

up since two or three o'clock, "studying the night effects," he said,

listening to the roaring and crunching of the charging ice as it came

out of

Endicott Arm, spreading out like the skirmish line of an army and

grinding

against the rocky point just below us. He had even attempted a

moonlight climb

up the sloping face of a high promontory with Stickeen as his

companion, but

was unable to get to the top, owing to the smoothness of the granite

rock. It

was newly glaciated — this whole region — and the hard rubbing

ice-tools had

polished the granite like a monument. A hasty meal and we were off. "We'll find it this

time," said Muir. A miner crawled out of

his blankets and came to see us

start. "If it's scenery you're after," he said, ten miles up the bay

there's the nicest canyon you ever saw. It has no name that I know of,

but it

is sure some scenery." The long, straight fiord

stretched southeast into the heart

of the granite range, its funnel shape producing tremendous tides.

When the

tide was ebbing that charging phalanx of ice was irresistible, storming

down

the canyon with race-horse speed; no canoe could stem that current. We

waited

until the turn, then getting inside the outer fleet of icebergs we

paddled up

with the flood tide. Mile after mile we raced past those smooth

mountain

shoulders; higher and higher they towered, and the ice, closing in upon

us,

threatened a trap. The only way to navigate safely that dangerous

fiord was

to keep ahead of the charging ice. As we came up towards the end of the

bay the

narrowing walls of the fiord compressed the ice until it crowded

dangerously

around us. Our captain, Lot, had taken the precaution to put a false

bow and

stern on his canoe, cunningly fashioned out of curved branches of trees

and hollowed

with his hand-adz to fit the ends of the canoe. These were lashed to

the bow

and stern by thongs of deer sinew. They were needed. It was like

penetrating an

arctic ice-floe. Sometimes we would have to skirt the granite rock and

with our

poles shove out the ice-cakes to secure a passage. It was fully thirty

miles to

the head of the bay, but we made it in half a day, so strong was the

current of

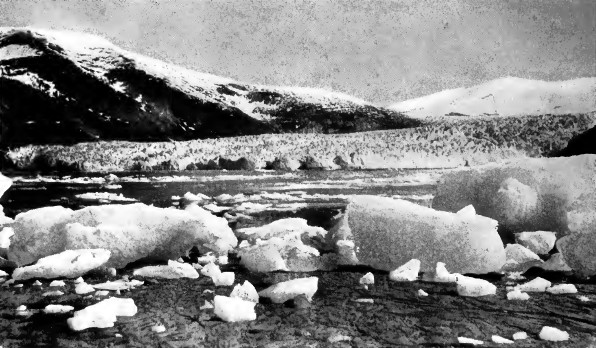

the rising tide. I shall never forget the

view that burst upon us as we

rounded the last point. The face of the glacier where it discharged its

icebergs was very narrow in comparison with the giants of Glacier Bay,

but the

ice cliff was higher than even the face of Muir Glacier. The narrow

canyon of

hard granite had compressed the ice of the great glacier until it had

the

appearance of a frozen torrent broken into innumerable crevasses, the

great

masses of ice tumbling over one another and bulging out for a few

moments

before they came crashing and splashing down into the deep water of the

bay.

The fiord was simply a cleft in high mountains, and the depth of the

water

could only be conjectured. It must have been hundreds of feet, perhaps

thousands, from the surface of the water to the bottom of that

fissure.

Smooth, polished, shining breasts of bright gray granite crowded above

the

glacier on every side, seeming to overhang the ice and the bay.

Struggling

clumps of evergreens clung to the mountain sides below the glacier,

and up,

away up, dizzily to the sky towered the walls of the canyon. Hundreds

of other

Alaskan glaciers excel this in masses of ice and in grandeur of front,

but none

that I have seen condense beauty and grandeur to finer results. "What a plucky little

giant!" was Muir's

exclamation as we stood on a rock-mound in front of this glacier. "To

think of his shouldering his way through the mountain range like this!

Samson,

pushing down the pillars of the temple at Gaza, was nothing to this

fellow.

Hear him roar and laugh!" Without consulting me

Muir named this "Young

Glacier," and right proud was I to see that name on the charts for the

next ten years or more, for we mapped Endicott Arm and the other arm of

Sumdum

Bay as we had Glacier Bay; but later maps have a different name. Some

ambitious

young ensign on a surveying vessel, perhaps, stole my glacier, and

later

charts give it the name of Dawes. I have not found in the Alaskan

statute books

any penalty, attached to the crime of stealing a glacier, but certainly

it

ought to be ranked as a felony of the first magnitude, the grandest of

grand

larcenies. A couple of days and

nights spent in the vicinity of Young

Glacier were a period of unmixed pleasure. Muir spent all of these days

and

part of the nights climbing the pinnacled mountains to this and that

viewpoint,

crossing the deep, narrow and dangerous glacier five thousand feet

above the

level of the sea, exploring its tributaries and their side canyons,

making

sketches in his note-book for future elaboration. Stickeen by this time

constantly followed Muir, exciting my jealousy by his plainly

expressed

preference. Because of my bad shoulder the higher and steeper ascents

of this

very rugged region were impossible to me, and I must content myself

with two

thousand feet and even lesser climbs. My favorite perch was on the

summit of a

sugar-loaf rock which formed the point of a promontory jutting into

the bay

directly in front of my glacier, and distant from its face less than a

quarter

of a mile. It was a granite fragment which had evidently been broken

off from

the mountain; indeed, there was a niche five thousand feet above into

which it

would exactly fit.. The sturdy evergreens struggled halfway up its

sides, but

the top was bare. On this splendid pillar I

spent many hours. Generally I

could see Muir, fortunate in having sound arms and legs, scaling the

high

rock-faces, now coming out on a jutting spur, now spread like a spider

against

the mountain wall. Here he would be botanizing in a patch of green that

relieved the gray of the granite, there he was dodging in and out of

the blue

crevasses of the upper glacial falls. Darting before him or creeping

behind

was a little black speck which I made out to be Stickeen, climbing

steeps up

which a fox would hardly venture. Occasionally I would see him dancing

about at

the base of a cliff too steep for him, up which Muir was climbing, and

his

piercing howls of protest at being left behind would come echoing down

to me. But chiefly I was

engrossed in the great drama which was

being acted before me by the glacier itself. It was the battle of

gravity with

flinty hardness and strong cohesion. The stage setting was perfect; the

great

hall formed by encircling mountains; the side curtains of dark-green

forest,

fold on fold; the gray and brown top-curtains of the mountain heights

stretching clear across the glacier, relieved by vivid moss and flower

patches

of yellow, magenta, violet and crimson. But the face of the glacier was

so high

and rugged and the ice so pure that it showed a variety of blue and

purple

tints I have never seen surpassed — baby-blue, sky-blue, sapphire, turquoise,

cobalt, indigo, peacock, ultra-marine, shading at the top into lilac

and amethyst.

The base of the glacier-face, next to the dark-green water of the bay,

resembled a great mass of vitriol, while the top, where it swept out of

the

canyon, had the curves and tints and delicate lines of the iris. But the glacier front was

not still; in form and color it was

changing every minute. The descent was so steep that the glacial rapids

above

the bay must have flowed forward eighty or a hundred feet a day. The

ice cliff,

towering a thousand feet over the water, would present a slight incline

from

the perpendicular inwards toward the canyon, the face being white from

powdered

ice, the result of the grinding descent of the ice masses. Here and

there would

be little cascades of this fine ice spraying out as they fell, with

glints of

prismatic colors when the sunlight struck them. As I gazed I could see

the

whole upper part of the cliff slowly moving forward until the ice-face

was

vertical. Then, foot by foot it would be pushed out until the upper

edge

overhung the water. Now the outer part, denuded of the ice powder,

would

present a face of delicate blue with darker shades where the mountain

peaks

cast their shadows. Suddenly from top to bottom of the ice cliff two

deep lines

of prussian blue appeared. They were crevasses made by the ice current

flowing

more rapidly in the center of the stream. Fascinated, I watched this

great

pyramid of blue-veined onyx lean forward until it became a tower of

Pisa, with

fragments falling thick and fast from its upper apex and from the

cliffs out of

which it had been split. Breathless and anxious, I awaited the final

catastrophe, and its long delay became almost a greater strain than I

could

bear. I jumped up and down and waved my arms and shouted at the glacier

to

"hurry up.”  TAKU GLACIER There followed an excursion into Taku Bay, that miniature of Glacier Bay, That night I waited

supper long for Muir. It was a good

supper — a mulligan stew of mallard duck, with biscuits and coffee.

Stickeen

romped into camp about ten o'clock and his new master soon followed. "Ah!" sighed Muir between

sips of coffee,

"what a Lord's mercy it is that we lost this glacier last fall, when we

were pressed for time, to find it again in these glorious days that

have

flashed out of the mists for our special delectation. This has been a

day of

days. I have found four new varieties of moss, and have learned many

new and

wonderful facts about World-shaping. And then, the wonder and glory!

Why, all

the values of beauty and sublimity — form, color, motion and sound —

have been

present to-day at their very best. My friend, we are the richest men in

all the

world to-night." Charging down the canyon

with the charging ice on our

return, we kept to the right-hand shore, on the watch for the mouth of

the

canyon of " some scenery." We had not been able to discover it from

the other side as we ascended the fiord. We were almost swept past the

mouth of

it by the force of the current. Paddling into an eddy, we were

suddenly halted

as if by a strong hand pushed against the bow, for the current was

flowing like

a cataract out of the narrow mouth of this side canyon. A rocky shelf

afforded

us a landing place. We hastily unloaded the canoe and pulled it up upon

the

beach out of reach of the floating ice, and there we had to wait until

the next

morning before we could penetrate the depths of this great canyon. We shot through the mouth

of the canyon at dangerous speed.

Indeed, we could not do otherwise; we were helpless in the grasp of

the

torrent. At certain stages the surging tide forms an actual fall, for

the

entrance is so narrow that the water heaps up and pours over. We took

the

beginning of the flood tide, and so escaped that danger; but our speed

must

have been, at the narrows, twenty miles an hour. Then, suddenly, the

bay

widened out, the water ceased to swirl and boil and the current became

gentle. When we could lay aside

our paddles and look up, one of the

most glorious views of the whole world "smote us in the face," and

Muir's chant arose, "Praise God from whom all blessings flow." Before entering this bay

I had expressed a wish to see

Yosemite Valley. Now Muir said: "There is your Yosemite; only this one

is

on much the grander scale. Yonder towers El Capitan, grown to twice his

natural

size; there are the Sentinel, and the majestic Dome; and see all the

falls.

Those three have some resemblance to Yosemite Falls, Nevada and Bridal

Veil;

but the mountain breasts from which they leap are much higher than in

Yosemite,

and the sheer drop much greater. And there are so many more of these

and they

fall into the sea. We'll call this Yosemite Bay — a bigger Yosemite, as

Alaska

is bigger than California." Two very beautiful

glaciers lay at the head of this canyon.

They did not descend to the water, but the narrow strip of moraine

matter without

vegetation upon it between the glaciers and the bay showed that it had

not been

long since they were glaciers of the first class, sending out a stream

of

icebergs to join those from the Young Glacier. These glaciers

stretched away

miles and miles, like two great antennae, from the head of the bay to

the top

of the mountain range. But the most striking features of this scene

were the

wonderfully rounded and polished granite breasts of these great

heights. In one

stretch of about a mile on either side of the narrow bay parallel

mouldings,

like massive cornices of gray granite, five or six thousand feet high,

overhung the water. These had been fluted and rounded and polished by

the

glacier stream, until they seemed like the upper walls and Corinthian

capitals of

a great temple. The power of the ice stream could be seen in the

striated

shoulders of these cliffs. What awful force that tool of steel‑ like

ice must

have possessed, driven by millions of tons of weight, to mould and

shape and

scoop out these flinty rock faces, as the carpenter's forming plane

flutes a

board! When we were half-way up

this wonderful bay the sun burst

through a rift of cloud. "Look, look!" exclaimed Muir. "Nature

is turning on the colored lights in her great show house." Instantly this severe,

bare hall of polished rock was

transformed into a fairy palace. A score of cascades, the most of them

invisible before, leapt into view, falling from the dizzy mountain

heights and

spraying into misty veils as they descended; and from all of them

flashed rainbows

of marvelous distinctness and brilliance, waving and dancing — a very

riot of

color. The tinkling water falling into the bay waked a thousand

echoes, weird,

musical and sweet, a riot of sound. It was an enchanted palace, and we

left it with

reluctance, remaining only six hours and going out at the turn of the

flood

tide to escape the dangerous rapids. Had there not been so many things

to see

beyond, and so little time in which to see them, I doubt if Muir would

have

quit Yosemite Bay for days. |